The Empty Hours (3 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective - Historical

“I don’t

know. It just doesn’t make sense. She wears underpants trimmed with Belgian

lace, but she lives in a crumby room-and-a-half with bath. How the hell do you

figure that? Two bank accounts, twenty-five bucks to cover her ass, and all she

pays is sixty bucks a month for a flophouse.”

“Maybe

she’s hot, Steve.”

“No.”

Carella shook his head. “I ran a make with C.B.I. She hasn’t got a record, and

she’s not wanted for anything. I haven’t heard from the feds yet, but I imagine

it’ll be the same story.”

“What

about that key? You said . . .”

“Oh,

yeah. That’s pretty simple, thank God. Look at this.”

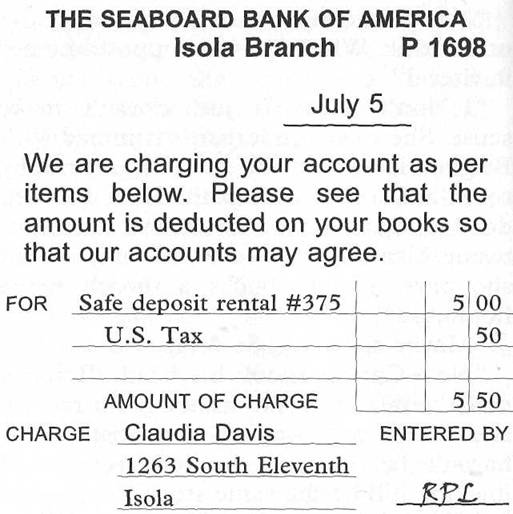

He

reached into the pile of checks and sorted out a yellow slip, larger than the

checks. He handed it to Meyer. The slip read:

“She

rented a safe-deposit box the same day she opened the new checking account,

huh?” Meyer said.

“Right.”

“What’s

in it?”

“That’s

a good question.”

“Look,

do you want to save some time, Steve?”

“Sure.”

“Let’s

get the court order

before

we go to the bank.”

* * * *

4

The manager of the Seaboard

Bank of America was a bald-headed man in his early fifties. Working on the

theory that similar physical types are

simpático,

Carella allowed Meyer to

do most of the questioning. It was not easy to elicit answers from Mr.

Anderson., the manager of the bank, because he was by nature a reticent man.

But Detective Meyer Meyer was the most patient man in the city, if not the entire

world. His patience was an acquired trait, rather than an inherited one. Oh, he

had inherited a few things from his father, a jovial man named Max Meyer, but

patience was not one of them. If anything, Max Meyer had been a very impatient

if not downright short-tempered sort of fellow. When his wife, for example,

came to him with the news that she was expecting a baby, Max nearly hit the

ceiling. He enjoyed little jokes immensely, was perhaps the biggest practical

joker in all Riverhead, but this particular prank of nature failed to amuse

him. He had thought his wife was long past the age when bearing children was

even a remote possibility. He never thought of himself as approaching dotage,

but he was after all getting on in years, and a change-of-life baby was hardly

what the doctor had ordered. He allowed the impending birth to simmer inside

him, planning his revenge all the while, plotting the practical joke to end

all practical jokes.

When

the baby was born, he named it Meyer, a delightful handle which when coupled

with the family name provided the infant with a double-barreled monicker: Meyer

Meyer.

Now

that’s pretty funny. Admit it. You can split your sides laughing over that one,

unless you happen to be a pretty sensitive kid who also happens to be an

Orthodox Jew, and who happens to live in a predominately Gentile neighborhood.

The kids in the neighborhood thought Meyer Meyer had been invented solely for

their own pleasure. If they needed further provocation for beating up the Jew

boy, and they didn’t need any, his name provided excellent motivational fuel. “Meyer

Meyer, Jew on fire!” they would shout, and then they would chase him down the

street and beat hell out of him.

Meyer

learned patience. It is not very often that one kid, or even one grown man, can

successfully defend himself against a gang. But sometimes you can talk yourself

out of a beating. Sometimes, if you’re patient, if you just wait long enough,

you can catch one of them alone and stand up to him face to face, man to man,

and know the exultation of a fair fight without the frustration of overwhelming

odds.

Listen,

Max Meyer’s joke was a harmless one. You can’t deny an old man his pleasure.

But Mr. Anderson, the manager of the bank, was fifty-four years old and totally

bald. Meyer Meyer, the detective second grade who sat opposite him and asked

questions, was also totally bald. Maybe a lifetime of sublimation, a lifetime

of devoted patience, doesn’t leave any scars. Maybe not. But Meyer Meyer was

only thirty-seven years old.

Patiently

he said, “Didn’t you find these large deposits rather odd, Mr. Anderson?”

“No,”

Anderson said. “A thousand dollars is not a lot of money.”

“Mr.

Anderson,” Meyer said patiently, “you are aware, of course, that banks in this

city are required to report to the police any unusually large sums of money

deposited at one time. You are aware of that, are you not?”

“Yes, I

am.”

“Miss

Davis deposited four thousand dollars in three weeks’ time. Didn’t that seem

unusual to you?”

“No.

The deposits were spaced. A thousand dollars is not a lot of money, and not an

unusually large deposit.”

“To me,”

Meyer said, “a thousand dollars is a lot of money. You can buy a lot of beer

with a thousand dollars.”

“I don’t

drink beer,” Anderson said flatly.

“Neither

do I,” Meyer answered.

“Besides,

we

do

call the police whenever we get a very large deposit, unless the

depositor is one of our regular customers. I did not feel that these deposits

warranted such a call.”

“Thank

you, Mr. Anderson,” Meyer said. “We have a court order here. We’d like to open

the box Miss Davis rented.”

“May I

see the order, please?” Anderson said. Meyer showed it to him. Anderson sighed

and said, “Very well. Do you have Miss Davis’ key?”

Carella

reached into his pocket. “Would this be it?” he said. He put a key on the desk.

It was the key that had come to him from the lab together with the documents

they’d found in the apartment.

“Yes,

that’s it,” Mr. Anderson said. “There are two different keys to every box, you

see. The bank keeps one, and the renter keeps the other. The box cannot be

opened without both keys. Will you come with me, please?”

He

collected the bank key to safety-deposit box number 375 and led the detectives

to the rear of the bank. The room seemed to be lined with shining metal. The

boxes, row upon row, reminded Carella of the morgue and the refrigerated

shelves that slid in and out of the wall on squeaking rollers. Anderson pushed

the bank key into a slot and turned it, and then he put Claudia Davis’ key into

a second slot and turned that. He pulled the long, thin box out of the wall and

handed it to Meyer. Meyer carried it to the counter on the opposite wall and

lifted the catch.

“Okay?”

he said to Carella.

“Go

ahead.”

Meyer

raised the lid of the box.

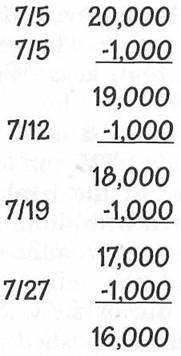

There

was $16,000 in the box. There was also a slip of note paper. The $16,000 was

neatly divided into four stacks of bills. Three of the stacks held $5,000 each.

The fourth stack held only $1,000. Carella picked up the slip of paper.

Someone, presumably Claudia Davis., had made some annotations on it in pencil.

“Make

any sense to you, Mr. Anderson?”

“No, I’m

afraid not.”

“She

came into this bank on July fifth with twenty thousand dollars in cash, Mr.

Anderson. She put a thousand of that into a checking account and the remainder

into this box. The dates on this slip of paper show exactly when she took cash

from the box and transferred it to the checking account. She knew the rules,

Mr. Anderson. She knew that twenty grand deposited in one lump would bring a

call to the police. This way was a lot safer.”

“We’d

better get a list of these serial numbers,’ Meyer said.

“Would

you have one of your people do that for us, Mr. Anderson?”

Anderson

seemed ready to protest. Instead, he looked at Carella, sighed, and said, “Of

course.”

The serial

numbers didn’t help them at all. They compared them against their own lists,

and the out-of-town lists, and the FBI lists, but none of those bills was hot.

Only

August was.

* * * *

5

Stewart City hangs in the hair

of Isola like a jeweled tiara. Not really a city, not even a town, merely a

collection of swank apartment buildings overlooking the River Dix, the

community had been named after British royalty and remained one of the most

exclusive neighborhoods in town. If you could boast of a Stewart City address,

you could also boast of a high income, a country place on Sands Spit, and a

Mercedes Benz in the garage under the apartment building. You could give your

address with a measure of snobbery and pride

— you were, after all,

one of the elite.

The

dead girl named Claudia Davis had made out a check to Management Enterprise,

Inc., at 13 Stewart Place South, to the tune of $750. The check had been dated

July nine, four days after she’d opened the Seaboard account.

A cool

breeze was blowing in off the river as Carella and Hawes pulled up.

Late-afternoon sunlight dappled the polluted water of the Dix. The bridges connecting

Calm’s Point with Isola hung against a sky awaiting the assault of dusk.

“Want

to pull down the sun visor?” Carella said.

Hawes

reached up and turned down the visor. Clipped to the visor so that it showed

through the windshield of the car was a hand-lettered card that read POLICEMAN

ON DUTY CALL

— 87TH PRECINCT. The car, a 1956 Chevrolet, was Carella’s own.

“I’ve

got to make a sign for my car,” Hawes said. “Some bastard tagged it last week.”

“What

did you do?”

“I went

to court and pleaded not guilty. On my day off.”

“Did

you get out of it?”

“Sure.

I was answering a squeal. It’s bad enough I had to use my own car, but for Pete’s

sake, to get a ticket!”

“I

prefer my own car,” Carella said. “Those three cars belonging to the squad are

ready for the junk heap.”