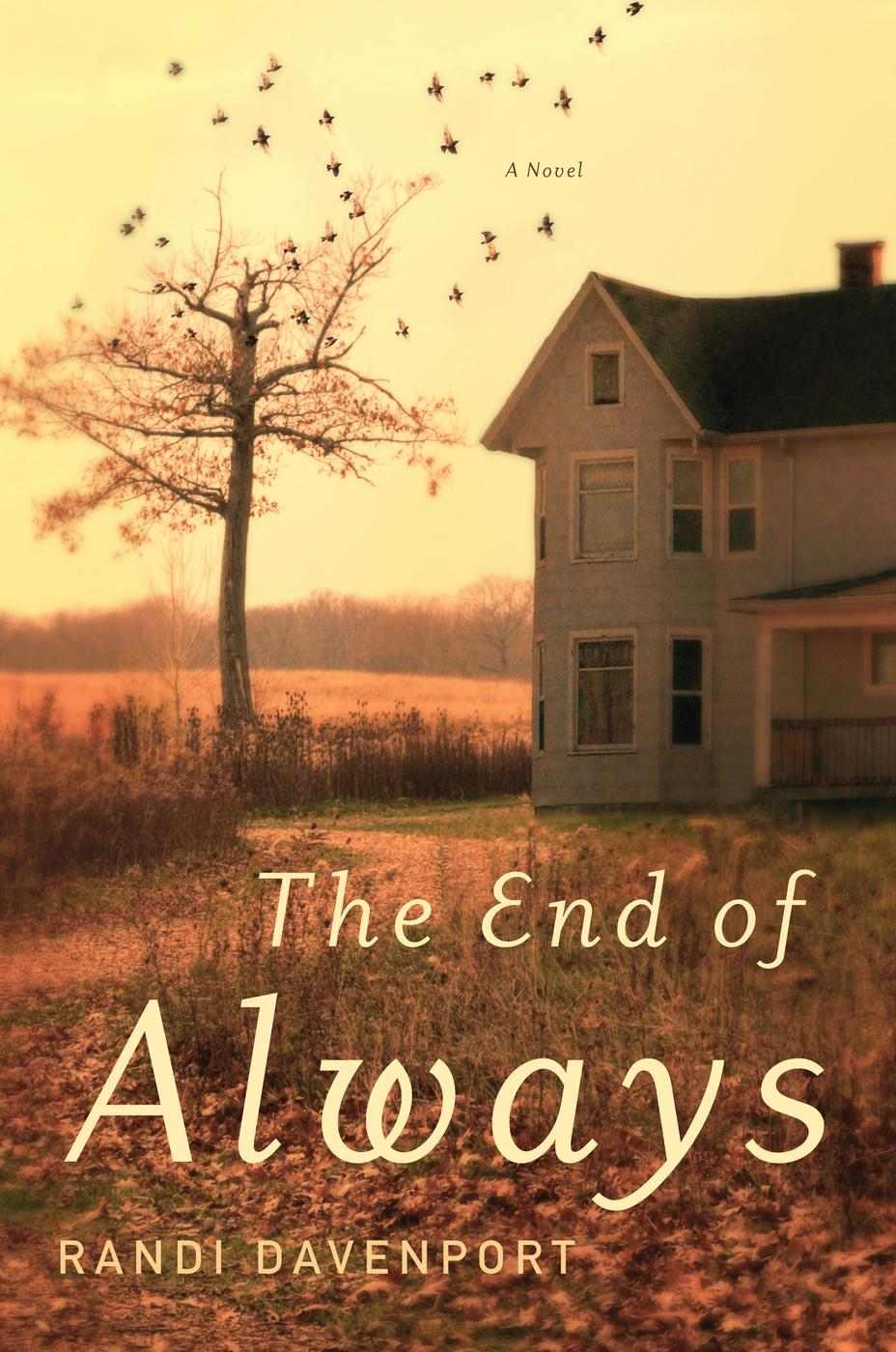

The End of Always: A Novel

Read The End of Always: A Novel Online

Authors: Randi Davenport

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For all the Reehs women everywhere

All the greatest things are simple, and many can be expressed in a single word: Freedom; Justice; Honour; Duty; Mercy; Hope.

—Winston Churchill

W

hen my father came to America, he brought my mother and my sister Martha to Waukesha, Wisconsin, where I was born and grew up. Then as now, the town stood on a vast tableland of grass west of a lake so broad you could not see from coast to coast. Indians were here first, and the value of this land to the Menominee came from its proximity to the lake, which also made it a gathering place and later a trading town. Eventually, the place was overrun with traders who bartered with the Menominee for furs and skins and anything else they thought they could get for cheap. The traders all seemed to believe that prosperity came with opportunity, but like all men, the traders meant their own prosperity, their own opportunity. This is the American way.

A long trolley line ran through the middle of town and then on to Milwaukee, but in those days Waukesha was not so big that you could not walk the length of it if you had to. The richest people lived in houses on the limestone bluffs that overlooked the river. We lived on the other side of town in a plain house on a plain street. We had a kitchen at the back and a sitting room in the front and a little room next to that that I used as a bedroom even though it was just big enough to get a bed into and only had room for one window on the wall. In between our house and the houses on the bluffs lay the town center. This was where the business of the county was conducted, where ledgers and accountings and sales and foreclosures were kept and practiced and written and traded by men in dark suits and white shirts, their trousers held up by suspenders that fastened at the waistband of their pants with buttons made out of mother-of-pearl.

Once you got outside of Waukesha, there was farmland. You might see a farmer with his plow, the furrows opening up like rounded slits in the ground and falling away behind the blade as the axle passed over. Just beyond the farmland came the forest. This was my land. This was where I walked. Up under the trees where the earth seemed to curve away and the sky opened over me like a bell. That was where I could breathe. That was where I could think. That was where I felt free.

When he arrived in Waukesha in 1888, my father had every intention of buying land.

Land.

This was my father’s word for our future. There was no land for him on Rügen, only emperors who came and went, dividing and redividing the country to suit their own interests. Every so often, the island changed hands. It was a fierce land of fierce people, and I believe a good part of my temperament does come from the character of the place, even if I have never set eyes on it. Rügen belonged to the far north and along with its almighty determination apparently had enchantments entirely its own.

Martha insists that she has no memory of the trip over the ocean, but this is not the only thing for which Martha claims amnesia, so you will forgive me if I do not entirely believe her. Willie and Hattie and Alvin and I were born here, which made us Americans. I often felt that we stood on the other side of a line my mother and father and sister could not see and did not know existed. When I was small, my father would open his atlas to show me the route they had taken, but all I saw was a flat blue page printed with the word

Atlantic

and the gnarled edge of Europe, which did not appear any more real to me than a page in a book, which is not the same as a country where someone could actually live. America, on the other hand, was the land beneath my feet. I walked America every day.

The year I turned seventeen, summer burned like fire. Heat lingered even after sunset and the air did not cool, not even in the blue shadows under the trees where the ground went black. The lake turned brown at the shore and the stones on the beach burned hot and branches lost in storms were cast up on the rocks, where they went white and then fell to dust. It did not rain and the creeks faded and the Fox River shrank between its banks.

One night in August, I swept the back porch and watched dry lightning flare over the horizon. Behind me, Martha clattered the supper dishes as she put them away. Then she came outside and stood next to me and wiped her forehead with the back of her arm. “It’s so hot,” she said. “I don’t think I can stand any more.”

We stood and watched the lightning.

“How is he?” I asked.

“Mother thinks he’s better.” But she sighed deeply and pushed her hair back from her temples, a gesture so quiet and oblique I knew she disagreed.

“Isn’t that good?”

She didn’t reply but only watched the sky. It paled and went dark and paled and went dark. From far away came the low rumble of the interurban.

“I’m not just going to stand here,” I said.

Martha did not look at me. “Do what you want,” she said.

At the top of the stairs, yellow light made a slit in the dark hallway. I tapped on the bedroom door and then leaned against it and stood in the doorway. My mother lay on the bed with Alvin stretched out on her chest. Even from across the room I could see that his pulse beat in his temple like something inside of him was desperate to get out.

My little brother carried a name my father had picked out. He thought the name had a certain ring of newness to it, a certain American sound. My mother thought it sounded like the name you give to a horse. But she had to live with the choice. We all had to live with my father’s choices. He ran our household like he was the king and we were his subjects. His hand had the final say, and there was no word more certain to compel our obedience.

When Alvin first got sick, my mother thought he was teething. She rubbed whiskey on his gums to settle him. But a fever came on, and my mother had spent most of the day before walking Alvin up and down or trying to get him to sleep or laying wet rags on his head. By this morning he merely slumped in her arms and stared up at us with a hard sparkle in his eyes. Now his eyes were closed, and he did not even seem sweaty in the heat but lay as still as the toy babies they sold at the dry-goods store. My mother rubbed his back.

“Is he better?” I asked.

Before my mother could answer, Alvin made a guttural sound and began to fling himself up and down like a fish fighting a line. My mother cried out. After that, the only sound in the room came from the small whumps Alvin made as he pounded his head against my mother’s chest. When he finally went still, my mother touched his forehead and listened for his breath. It came in harsh, shallow waves. “Tell Martha run and get the doctor,” she said then. “I do not know what else to do.”

My mother had already buried one son, her first child, who died before he was a year old. She and my father had left him behind when they left Rügen. When she told us about him, he was so far away and never to be seen that it seemed he had never existed at all. Then, the summer Willie turned fourteen, my father sent him out to work. My father told us that work in a mining camp would turn Willie into a man. What it really did was turn Willie into someone we never saw again. The day he left, he packed a comb and a clean shirt and set out from our front porch. I watched him until he disappeared, but he never looked back and certainly did not look back at me, even though I had been closest to him and had often lain awake at night while he sat on the edge of my bed and talked to me about how things would be different when he grew up. His house would not be like this one. He would get away and stay away. I could count on that. Later, when he did not write and did not return, I told myself he must be out there somewhere. But I felt a hard hurt whenever anyone said his name and then a kind of flattening, as if the mystery of what had happened to him had to be turned into a sheet of paper that I could fold and put away.

The doctor rolled his cart into our drive and tied off his horse, which stood blowing and swatting flies at the fence rail. He called to Martha to hold on, for he’d be right there to help her down. Then he came toward me out of the dark with a cheerful expression on his face. “Hot as Hades,” he said as I led him upstairs. “I don’t believe it can get any worse than this.” But then I pushed the bedroom door open and he saw Alvin and he did not sound so jovial after that.

“Elise,” he said. “You just lie still. There’s no point in moving that child. Let’s see if we can’t get a good look at him where he is.” He sat on the edge of the bed with the tubes of his stethoscope protruding from his ears. He moved the silver disc across Alvin’s back and curved his palm around the back of Alvin’s neck and let his hand rest there. “Not an exact measurement,” he told my mother. “But I find it usually gives me a good idea.”

Martha and I stood shoulder to shoulder in the doorway. I watched the doctor as he touched Alvin and then I watched Alvin, who did nothing but lie on my mother’s chest and did not even open his eyes. He seemed to be disappearing by the second, and I wondered how long it would be before he vanished entirely. Even now, he did not seem to be Alvin but instead seemed to be the memory of Alvin, still tethered among us, but who knew for how much longer. My stomach lurched at the thought and I looked at my mother, who was now openly weeping, and my throat closed and then I felt tears come to my eyes.

The doctor said that Alvin’s illness was not uncommon. You often saw it in the summertime among children whose mothers fed their children things they should not have fed them, meat that had been cooked but not put on ice, something left over from breakfast. He wished these women would do a better job, but what was he to do about it? There was nothing he could do. And where Alvin was concerned, the illness would have to run its course. It would have the predictable result, and my mother should expect that by morning. Then he put his stethoscope back in his bag and told me he’d left his hat on the kitchen table and he could pick it up as I showed him out. He’d send a bill next week.

After the doctor left, my mother remained on her bed with Alvin still stretched out on her chest. But the doctor was wrong and Alvin did not die by morning. He lay like that for another half a day, and Martha and I took turns bringing my mother water so she could drink. Hattie sewed a little doll from leftover felt and tried to interest Alvin in this, as if a toy would pull him from the place he’d gone. When he died, we were all in the room together. We heard the rattle of his breath and then the silence that followed.

My mother laid Alvin in his crib and then she put on a hat and walked into town, where she hired a photographer to take his picture. She insisted that his eyes be left open until the picture was done. The man stood my brother in his box against the wall, and my father stood in the doorway next to it, his hat in one hand, his other hand in the pocket of his trousers. In the picture, this was how he appeared, as if only part of a man, his head missing and his dark legs disappearing, his suspenders loose over his unruly white shirt. Martha was nineteen that day and Hattie was twelve. My mother was thirty-eight. After that, with Willie gone and Alvin dead, my father was left alone with daughters and a wife, a house full of women he could do with as he pleased.

The only one to follow my parents from Rügen was my mother’s brother Carl, who sailed from Hamburg on a ship called the

California

the year after my parents left. He was a tall man with red hair and a red mustache. I had no trouble picturing him on deck, his hair blowing and spray rising from the sea. When he got here, he took a job at a dairy. When he grew tired of that, he went to work on a farm, and when he wearied of that, he made a bed of blankets on the floor and lived in our front room. He left his work boots on the front porch until someone stole them and my mother had to appeal to my father for money to buy a new pair. Not long after that, he took a job at a machine shop and moved into a boardinghouse in Milwaukee.

My father disliked Carl but I could not understand why. I loved Carl. He did card tricks. He brought gifts for my mother when he came to see her. A bottle of lavender water. A pair of beautiful white lace gloves, which she kept in a box and took out to look at but never wore. But if Carl tried to give us paper dolls or jacks, my father would take the toys away and give them back to us on our birthdays, with a card made out of a piece of folded newspaper and signed with his own name.

My father was not a godly man. To my knowledge, he never set foot in a church after the day he married my mother. Instead, he worshipped at the altar of socialism, that font of good wisdom that poured over Waukesha and brought us laws about clean water and education, which I suppose can be said to have done some good in the end. My father, for his part, talked about the rise of the workingman the way someone devout in other ways talked about Jesus. My father had his heart set on the idea that men live in chains.

The word

land

seems to have a simple definition but it can mean more than the obvious thing. It can mean the ground under your feet, the place you walk, the place you pitch your tent or build your house or find at the edge of a body of water that would otherwise take you whole. But it can also be the place you come to, the way my parents landed in Waukesha. For my father, land was the one thing he wanted above all else. For him,

land

was the word for desire. What he would not do for land, he would say. Practically nothing at all. He could already see the cows lined up at the barn at milking time. The buckets he would decant into a tank. All of us at work to make sure he turned out rich. A dream of land that he was sure would turn solid under his feet: a white farmhouse, a bank of raspberry bushes, a stream that never ran dry.

But when my father got here, he found that he was more than half a century too late. The towns and cities were not settlements but places with buildings made of brick and stone and farms already developed. The small amount of cash that he carried was not sufficient to buy. His first job in Waukesha was in a flour mill where the miller still spoke German. When my father had learned some English, he moved on to an ironworks where the fires from the foundry singed the hair from his face and the hair just over the tops of his ears. It grew back but he did not know that it would. For a time he raged about working conditions that permitted a man to be scorched like that, right down to the skin. Then he took a job as a barman at a saloon on St. Paul Street. He worked nights and came home at dawn to a house he rented from a man who owned three hotels and a livery stable.