The End of Dieting: How to Live for Life (10 page)

Read The End of Dieting: How to Live for Life Online

Authors: Joel Fuhrman

Take, for instance, the thorny issue of EPA and DHA supplementation within the low-fat vegan community. EPA and DHA, two long-chain fatty acids, are essential to fetal development, cardiovascular function, and the prevention of dementia. The only problem is that the richest source of EPA and DHA is fatty fish. While it’s perfectly reasonable—and perfectly healthy—to avoid fatty fish for a number of reasons, there are still a number of health benefits to including omega-3 fatty acids in our regular diet. Most advocates of a low-fat vegan diet refute this view and resist findings that may contradict their opinions, as if their minds are already closed. It almost seems that they are resistant to recognizing that many people may need a source of DHA fat, because that would mean that a vegan diet is not the best natural diet for man. For some in this community, it looks like their philosophical preferences cloud their judgment of the available evidence. When there are only a limited number of long-term trials available, we have to rely more on clinical evidence and be cautious so all people’s individual health needs are considered.

While EPA acts to increase cerebral blood flow via eicosanoids (messengers in the nervous system), DHA increases membrane fluidity, which enables membrane function and signaling properties. DHA

also increases the growth of neurons and the uptake of glucose in the brain, important steps in neurotransmission, and helps promote neuronal survival while protecting the brain from degeneration.

Cognitive decline in the elderly is often marked by a decrease in plasma DHA levels. A report from the Framingham Heart Study, for instance, showed that people with plasma DHA levels in the top quartile of values had a significantly lower risk (47 percent) of developing all-cause dementia than those in the bottom quartile.

29

Other studies have corroborated this, demonstrating a linear relationship between the intake of DHA and EPA and the prevention of cognitive decline.

30

Similarly, patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease show a lower content of DHA in the gray matter of the frontal lobe and hippocampus of the brain than patients who don’t have Alzheimer’s.

31

Epidemiological and animal studies also suggest that omega-3 fatty acids protect against cognitive decline.

32

At the same time, a two-year study demonstrated that DHA and EPA supplementation improved memory.

33

These findings were corroborated in another randomized placebo-controlled trial with subjects who had habitually low intakes of fish and seafood.

34

Over a six-month period, the participants consumed either 1 gram of DHA per day or a placebo. Their cognitive performance was tested before and after the intervention. Those taking DHA supplements improved their memory and cognitive reaction times.

More recently, DHA has been linked to depression. Vegans with strikingly low levels of omega-3 EPA and DHA, for instance, are more at risk for depression, postpartum depression, and/or neurological decline later in life. A large study of eight hundred suicides, for example, found that the likelihood of suicide was 62 percent higher in people with low levels of DHA. What’s more, a 14 percent increase in the risk of suicide death came with each standard deviation below normal DHA levels.

35

Interventional studies of people with major depression have shown omega-3 fatty acids to be effective in fighting depression.

36

Having served as the primary physician since the early 1970s for this community of vegans eating a healthy, whole food–based diet, as well as raw food vegans since the early 1990s, I am in a unique position to point out how such a rigid ideology can sometimes prevent someone from reaching optimal health. Some people even refused to take vitamin B

12

, a separate but serious issue, resulting in the death of some staunch philosophical naturalists. However, this experience enabled me to observe and investigate the cause of neurological problems that developed in this community that were not secondary to B

12

deficiency, by checking their level of omega-3 fatty acids.

A pattern emerged in those with later-life neurological decline: when I then checked their DHA levels, they were either extremely low or undetectable. I have since tested blood levels of scores of vegans and found similar deficiencies in many, even if they were consuming adequate amounts of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), the short-chain omega-3 fatty acid found in appreciable quantity in walnuts, hemp and chia seeds, flaxseeds, and soybeans.

On its own, ALA is an inefficient source of DHA because its effect depends on its conversion first to EPA and then to DHA. This conversion varies considerably from person to person. Vegans who consume adequate sources of ALA still regularly exhibit low levels of EPA and, in particular, DHA. A trial of 165 nonsupplemented healthy vegans demonstrated this clearly.

37

Their mean red blood cell omega-3 index was 3.7, which indicated that the majority of the group suffered from suboptimal levels.

More concerning was that 27 percent showed levels below 3, a more serious deficiency, and 8.5 percent of participants showed an index below 2.5, a severe and potentially dangerous deficiency. Some people point to the dangers of high-dose supplementation with fish oil or of eating too much fish as reasons to not recommend any such supplements. It’s important to always remember that as with any nutrient, both too little and too much can be harmful. Recognizing the

potential risk of excess and avoiding excess is not a justification for remaining deficient.

Even though the existing science is not yet 100 percent definitive on the clinical implications of these deficiencies, enough evidence exists to show that EPA and DHA are semi-essential nutrients. I believe that people who abstain from eating fish, for whatever reason—personal, health, or ideological—should supplement their diets with low doses of EPA and DHA, or at least have a blood test to make sure that no significant deficiency exists. Ignoring this could place a person at significant risk later in life. Which is why I recommend that, if you cannot assure adequacy with blood work, non-fish eaters, vegans, and flexitarians take a low-dose algae supplement of about 200 milligrams of EPA and DHA per day, with at least 100 milligrams from the DHA component, to help prevent cognitive decline. As an alternative, I recommend one purified fish oil supplement every other day. A low-dose supplement can prevent deficiency and effectively raise red blood cell membrane fatty acid balance as measured with blood tests.

38

Some thought leaders in the vegan community disagree with and adamantly discourage following even this conservative recommendation, ignoring the nutritional and dietary needs of individuals who don’t fit into their one-size-fits-all rigid dietary paradigm. But there is simply no good reason to blindly adhere to an extremely low-fat vegan diet. No human population in the history of the earth has lived on an extremely low-fat vegan diet or any diet so radically low in fat. Science has shown that such a diet is far from ideal and can sometimes lead to disease. At the very least, it might prevent achieving optimal health and longevity, the ultimate goal of any diet style.

Yet many in this community are passionately attached to the “wisdom” of their preferred superstar doctors or to their desire to support animal rights or other altruistic advantages of a vegan diet. They have embraced leaders in the movement because of the reputations of those leaders and their support of veganism, but the fact

remains: nuts and seeds are important for protection against cancer and a heart disease–related death.

39

Inevitably, this extreme anti-fat dietary position will fade out of favor with time, as most incorrect dietary patterns usually do. More and more nutritional scientists are recognizing that fat isn’t always the villain it was once made out to be.

Just Eat

The bottom line is that you needn’t adopt any extreme fad diet; instead, eat lots of natural plant foods. Forget fat. Forget carbohydrates. Don’t worry about carbohydrate-to-protein ratios and—for your own sake—please ditch the diets. We need to stop the low-fat extremism, high-protein extremism, low-carb extremism, high-carb extremism, and high-fat extremism (believe it or not, this is gaining popularity too). None of this is constructive to solving our nation’s confusion and dietary quagmire.

Good nutrition meets, without excess, your macronutrient needs (fat, carbohydrate, and protein—the three sources of calories) and provides for sufficient micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals—the parts of food that don’t contain calories). A broad range of macronutrients in your diet is acceptable, provided that you’re not overloading on calories—particularly empty calories that keep you locked in the vicious cycle of food addiction, toxic hunger, and overeating.

Health is the first consideration; weight is secondary. Focusing on health and a better quality of life is the only consistent way to maintain a favorable weight. To achieve an optimal amount of phytonutrients and other micronutrients, all you have to do is eat a large amount of vegetables every day. When you eat lots of vegetables, especially green vegetables, you meet your body’s need for fiber and micronutrients without having to consume too many calories. To balance

out your diet and fill your daily caloric needs, choose an assortment of other foods that have protective health benefits—foods such as tomatoes, berries, beans, seeds, and mushrooms. Eat more fruits, beans, squash, peas, lentils, soybeans, nuts, and seeds. And less bread, potato, and rice—especially white rice.

Stop looking for diets and just eat as healthfully as possible. You know what healthful eating means, and if you eat healthfully enough, you won’t need to diet. No matter how popular they are, diets simply don’t work. So don’t diet. Eat only for health. It is important to thoroughly understand how harmful diets are for you and your health, which is the subject of the next chapter.

I

f we all understood that the secret to superior health and a long life was a steady diet of healthy greens and colorful vegetables, beans, walnuts, seeds, and fresh fruit, would the diet industry even exist? Our collective dietary ignorance is the only thing keeping that industry alive. If people understood the basic principles of nutritional excellence, they would understand that they need to eat healthfully, and by doing so they would achieve their ideal weight and never feel compelled to diet again. They wouldn’t jump from one popular diet book to another looking for a quick fix. They wouldn’t have to.

When you lose weight and gain it back again, you only end up fatter than before. And this regained weight is harder to lose. Even worse, all this new extra weight makes you more susceptible to disease than before you started dieting. In other words, unless you keep off the fat you lost, you’re in danger.

Cycling your weight up and down takes a toll on the body. When you lose weight, you lose both fat and muscle. When you put weight back on, however, you put it back on mostly as fat. Muscle takes longer to restore—and that’s only from consistent, rigorous exercise. A 1993 study examined the correlation between weight cycling and obesity in rats. Researchers restricted the caloric intake of one group of rats and kept a second group of rats on their regular diet. When they put the first group back on its regular diet, the rats in that group ended up with more body fat than the rats that were fed the same number of calories as part of their regular diet.

1

The consistency of caloric intake made for a leaner rat, while the fluctuation of calories led to a fatter rat.

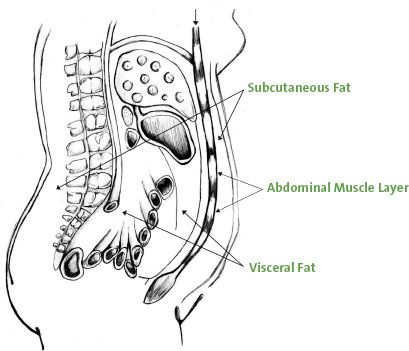

The same holds true for humans. When we cut back our calories dramatically in the hopes of losing weight and then increase them once we reach our “goal weight,” our lipogenic enzymes, the enzymes that store fat, shoot up. Such weight cycling is particularly harmful. It leads to more abdominal fat and visceral fat, the two types of body fat that place people at the highest risk of diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

2

Visceral fat is the fat under your abdominal wall. It surrounds your internal organs, engulfing your liver, intestines, kidney, pancreas, and heart with fat. Subcutaneous fat, on the other hand, is directly under your skin. It’s the fat you can pinch. Visceral fat, which is deeper inside your belly, is associated with a number of serious health concerns, including high blood pressure, insulin resistance, diabetes, and heart disease. When you diet, you lose subcutaneous fat. But when you go off the diet and gain weight, you put on more visceral fat. It takes years to get rid of visceral fat. And it’s almost never accomplished by crash dieting. Losing visceral fat requires a permanent commitment to healthy eating and healthy living through regular exercise.