The Essential Book of Fermentation (2 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

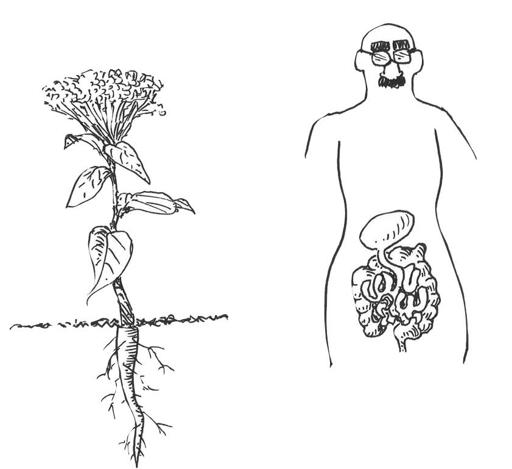

Then I had an epiphany—one of those visions that throws such a strong light on a subject that it changes the way you look at the world forever. I thought of a plant root and how at the small tips of the root, microscopic root hairs extend out into the soil to absorb the nutrients that microorganisms produce there. And then I thought of a human intestine and how it’s lined with microscopic villi—tiny projections much like root hairs—that point inward into the intestine and absorb nutrients from the decomposing elements of last night’s dinner.

I got it! An intestine is a root turned inside out! It carries its soil within it. This is the adaptation that eons ago separated animals from plants. It’s as if animals learned how to pull their roots out of the soil and turn them inside out so that they could walk around instead of being anchored to one spot.

This was an important insight for me, both in my job communicating the value of organic culture to a million readers and to me personally, as it showed me the way forward to a healthy diet. Practicing organic agriculture and eating fermented foods both result in health—organic agriculture yields a healthy farm ecosystem, and fermented food yields health in the gut ecosystem. The same processes are at work, with the same and similar microorganisms in many cases giving the same result: healthy food and healthy people.

The key here is the concept of an ecosystem: a network or web of interconnected and interdependent life forms that support one another. The study of ecology is a relatively new science, with many fathers and mothers, perhaps none as important as Howard Thomas Odum and his brother Eugene, who first synthesized many loosely affiliated ideas into the study of ecosystem ecology, which then developed into the science of ecology. Of course, pieces of the puzzle had been formulated as long ago as ancient Greece, where Aristotle and Theophrastus studied animals and their relationships. Darwin’s ideas were an important advance, and many others developed insights that finally clicked into place in the 1960s when the culture at large became concerned with the environment, and the science of ecology was born in its modern form.

The key concept is that everything is in some way connected to everything else, or as Francis Thompson, the British poet, put it:

All things by immortal power,

Near and Far

Hiddenly

To each other linked are,

That thou canst not stir a flower

Without troubling of a star.

This transcendental thought is not only undergirded by the study of ecology, but also by quantum mechanics, where two discrete atomic particles can affect each other simultaneously at a distance, with no apparent connection between them.

A second key concept is that when it comes to the health of an ecosystem, the more varied the life forms in it, the healthier it is, and that health is defined by the system’s stability; that is, its resistance to abrupt dislocation and change, as by a disease sweeping through, or by the sudden population explosion of a single species that swamps other members of the ecosystem. Rabbits overran Australia because there were no foxes or other predators to keep them in check. The phylloxera louse that attacks the roots of European varieties of grapevines nearly wiped out the French vineyards in the late nineteenth century, which were saved only when phylloxera-resistant native American grape rootstock was rushed to France and the European vines were grafted on it. Deadly lionfish escaped their aquariums in Florida not long ago, and now are found in the Atlantic all along the East Coast of the United States, again because their natural predators did not colonize the Atlantic with them. In a healthy ecosystem, there are adequate numbers of predators and prey, making the system stable. In any indigenous ecosystem, predators and prey have coevolved. The prey are a trophic niche that calls forth a predator to fill it. The ultimate prey animal is the plant-eating rodent—mouse, shrew, vole, rabbit, gopher, and many others—and predators from raptors to foxes to cats use rodents for food. This great diversity helps the stability of the ecosystem in which these animals are found. If an epidemic of disease knocks out an area’s foxes, raptors and cats will take up the slack. Diversity means that natural backup systems are in place, if and when needed.

A third concept is that ecosystem diversity is enhanced by recycling of the system’s nutrients by the fermentative process. In the wild, this happens naturally as each year’s tree leaves and herbaceous plants decay into the soil. In a forest managed for timber or firewood, cutting down the trees and carting them away without returning nutrients to the soil will eventually produce depleted soil that’s prone to erosion and wind damage and becomes increasingly devoid of life. The need for recycling is even more urgent on a farm. One of the big problems with conventional farms is that little waste is recycled. Soil becomes simply a means of propping up crops. Fertilizers are applied as soluble nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium compounds made in factories.

On the organic farm, however, farm wastes and manures are composted. What nutrients and elements are taken off the land and sold as farm products are more than replaced by the sheer proliferating biomass of microbes produced in the composting process. Finished compost has much more fertilizing power than the raw ingredients that went into the compost pile.

And so, in the human gut, the nutrients that are eliminated from your body in bowel movements are more than compensated for by the healthy ecosystem that digests the raw materials (your food). The gut is an internalized composting facility, feeding you exactly what nature intends for your health, when you need it, and in the forms that will do you the most good. Like any healthy ecosystem, the presence of a diverse mix of bacteria and yeasts is stable and disease-resistant, and in fact goes further in its protective function by bolstering your immune system.

Look to the organic garden for a clear outward depiction of what goes on inside you. There are no “bad” insects and “good” insects—only a healthy mix of plant-eating insects and insect-eating insects. Garden plants actually grow better when nibbled by insects because the nibbling stimulates the production of plant hormones, which support better growth and greater production of fruits and seeds. And the nibblers provide food for the insect eaters, and so the system is balanced and healthy. Now if you poison the insects, it’s the insect-eating bugs that are most susceptible to the pesticides. These chemicals reduce the system’s diversity in a selective way, killing off the most susceptible insects first. This makes it much more likely for plant eaters to proliferate and cause problems. And so it is with the use of antibiotics. If you are really being overwhelmed by an infection, antibiotics can be a lifesaver. But the routine use of antibiotics or their presence in your food will damage your intestinal ecosystem, making it much more likely for one or another pathogen to proliferate in your gut and cause further illness. The best way to prevent that is to maintain healthy gut ecology to begin with, or, if you must take an antibiotic, drink kefir and kombucha, eat fermented vegetables, and replenish the gut dwellers as fast as the antibiotics can kill them off.

These correspondences are manifold. The web of life is complicated in that picking that flower does indeed trouble that star. Consequences are hard to predict because the system is so complex. But that doesn’t mean it’s fruitless to try.

Let’s take a look at a rigorous and peer-reviewed scientific study to see if organic agriculture really works, and if it’s validated, what that might mean for our ingestion of probiotic foods. One such study was done in 2010 on a multi-university level that included private and public teams of scientists.

1

They found that the organic farms had strawberries with longer shelf life, greater dry matter (meaning that when the water was removed, there was more substance to the berries), and higher antioxidant activity and concentrations of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and phenolic compounds, but lower concentrations of phosphorus and potassium. “In one variety,” the scientists reported, “sensory panels judged organic strawberries to be sweeter and have better flavor, overall acceptance, and appearance than their conventional counterparts.” The organic farm soils had more biodiversity, took more nitrogen from the air and fed it to the plants, and degraded residual chemical pesticides; that is, the soils were healthier.

Here are the paper’s conclusions in its own words:

“Our findings show that the organic strawberry farms produced higher quality fruit and that their higher quality soils may have greater microbial functional capability and resilience to stress.”

You’ll have to forgive me a personal note here. After listening to apologists for the chemical agriculture industry deride organics for the last forty years, after hearing that half the population would have to starve if we went organic, and that there are no studies that show organic crops are in any way superior to those grown conventionally, I must say that this one study—joined by many, many others—should silence the critics. But of course it won’t. Press releases from agribusiness flacks and hacks continue.

The “strawberry fields” study implies something else: that just as a diversity of microbes is important in promoting positive health, so is diversity in foodstuffs. Our government suggests we eat at least three to five different kinds of fruits and vegetables a day. Many European countries suggest from seven to nine of these foods, and in Japan, citizens are advised to eat eleven or more different foods each day. It’s not the quantities that count, it’s the diversity of foods that produce a well-rounded diet. The food diversity supplies many different nutrients and substances that not only feed us directly, but that also stimulate a diversity of microbes in the gut, with each tasked to disassemble a different food.

Just as compost—a veritable seething pile of microscopic life—is the beating heart that feeds nutrients to the healthy organic garden, so is our intestine an internalized compost pile that feeds nutrients to our bodies.

The point of this book is that the same natural energies, processes, laws, tendencies, and holistic approaches to food production that reveal the superiority of organic agriculture are applicable to nutrition as augmented by fermented foods. In both cases, it’s working with nature’s ecosystems of microbes that produces the amazing results.

Our body is like a garden that needs organic care to thrive. That means avoiding toxic chemicals in our food, but it also means avoiding antibacterial soap when we wash. Scientists today are finding that the steep rise in autoimmune diseases among children may be due in large part to the fact that kids today spend a lot more time indoors with their computers and video games, are washed with antibacterial soaps, have their hands wiped frequently with hand sanitizer, and are watched over by parents who are concerned about ill effects from germs.

But this approach is backward. The scientists now say that it’s a lack of exposure to a wide variety of microbes that leads to compromised and underdeveloped immune systems; that the immune system needs lots of contact with germs to develop a diverse immune response. There was a time, not long ago, when kids got plenty dirty playing outside or working and helping around the family farm. The world outside is absolutely alive with microbes everywhere. In the organic garden, microbes are cherished, put to work recycling nutrients; they are like a flame in the soil, with the gardener heaping more fuel on this living fire with every shovelful of compost. The same approach to what we eat translates into a world of good health for us, and the way to that result is through the ingestion of fermented and fermenting foods.

And so our health is in some measure predicated on the health of our gut ecology, just as plant health is predicated on the health of soil ecology. It seemed right then and still seems right that nature builds the health of her advanced children (large plants and animals) on the strong ecological health of her smallest creatures: the fungi, yeasts, bacteria, actinomycetes, and other microorganisms that decompose organic matter. They are, after all, the destiny and source of all life.

Shakespeare, of course, said it all centuries ago when the friar in

Romeo and Juliet

remarks:

What’s Nature’s mother is her tomb.

What is her burying grave, that is her womb.

Introduction