The Essential Book of Fermentation (21 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

Milking dilates the teat canal, so the workers wash the teats with a combination of iodine solution and emollient to protect against infection and aid healing. At first, Liam said, the farm had problems with mastitis, which is usually cured by antibiotics on nonorganic farms. But on their visits to sheep farms in Tuscany and on Sardinia, they noticed that at the bottom of the teat cups the farmers had made a small hole in the evacuation tube that carries the milk from the animal to the tank. When they returned to California they punched similar holes in their tubes. Liam showed me how, when he held his finger over the holes he’d punched in his evacuation tubes, the suction surges of the milking machine would produce little back spurts that drove milk back into the teats. That was causing most of the mastitis, and the problem was solved by the simple measure of puncturing the suction tube so air from the hole would prevent the back-surge from reentering the teat.

The milk flowed from the cups to a pipe that carried it to a tank where it was cooled to 35ºF. The milk was kept in the tank until there was six days’ accumulation (later, in the high milk season in summer, it would be three days’ accumulation)—about 120 to 140 gallons. Now, I grew up next to a dairy farm, so I asked the obvious question: “What happens when you have a power outage and the milking machines don’t work?” The answer: “We milk a hundred and twenty-five ewes by hand twice a day.” I whistled a long “Whew!” But Liam said, “We visited a farm near Siena, Italy, where four hundred ewes were milked twice a day by hand.” I got uncomfortable just thinking about that, but Liam said the Siena farm was within a year of acquiring modern dairy equipment. “Most dairies in Italy have better equipment than we do, due to government support,” he said. The first group of sheep was now finished being milked, and the ewes ran out as another group filed in for their corn, their udders swinging fat and full behind and beneath them.

Before we went to the cheesemaking room, Liam gave me a taste of fresh, raw sheep’s milk. It was a beautiful light cream color, shiny and slightly viscous rather than pure white and watery with a slight bluish tinge like cow’s milk. It tasted smooth and creamy, too—delicious! “Sheep’s milk is like goat’s milk—it’s naturally homogenized. And it’s rich, about 6 percent butterfat and 5 percent protein, compared to a Holstein cow’s 4 percent butterfat and 3 percent protein—so the sheep’s milk shows that richness in the mouth,” Liam said. Bellwether’s cow’s milk is all from their neighbor’s Jersey herd, and Jersey milk is 5 percent fat and 4 percent protein, which, like sheep’s milk, makes a rich, flavorful cheese.

As he filled fourteen ten-gallon cans with the proceeds of six days’ milking, then washed everything down, Liam said that people are looking for raw milk cheese now: “It has a greater perceived value.” He talked about cheese as milk preservation. “It’s a traditional way of extending the time you can use milk. You can dry milk to a powder. You can sour it, and you can salt it. The souring with bacteria is particularly important. In raw milk, the balanced blend of natural bacteria prevents growth of strains that produce toxins.” From my research, I realized he was talking not only about lactobacilli turning lactose into lactic acid, but also about bacteriocins, compounds from beneficial bacteria that inhibit pathogenic bacteria. “The FDA is looking at one bacteriocin for its possible medical use,” he said. He wasn’t sanguine about the future of raw milk cheese, though. “It’s an inspector’s job to be proactive. When you have someone who’s employed to look out for the public safety, once they solve one problem, they have to go on to the next, which leads to zero tolerance for any possible danger, whether it’s warranted or not,” he said.

The cheesemaking room at Bellwether was once a room where young calves were kept in tight confinement, fed milk, and raised only long enough for them to produce the white, milk-fed veal prized by some Italian restaurants. The practice is increasingly recognized as cruel. Most of today’s veal is raised on pasture or in more humane conditions in barns. Certainly cheesemaking is an infinitely more benign use for this room, especially after seeing those happy ewes eager to file in for their morning corn and milking.

The room contains all stainless-steel equipment, bright overhead lights, and thick plastic sheeting on the walls so everything can be hosed down and cleaned after use. The equipment includes a double sink, stainless-steel tables, a stainless-steel pasteurizer with a digital readout (all Bellwether’s cow’s milk cheese is pasteurized), a tank with a hot water jacket used to warm the milk before turning it into cheese, and a 160-gallon-capacity tank where the sheep’s milk is curdled. This large tank sits up on a grillwork catwalk and has a lever that allows the cheesemaker to lower the front end so all the curds and whey will run down toward a valve inserted at the bottom of the front end and the tank can be completely emptied. As Liam’s workers poured the ten-gallon cans into the warming tank, I asked Liam where he’d learned how to make cheese.

“I took short courses at Cal Poly,” he said. “Knowing the science helps you understand the process.” He said that there are a lot of factors that influence the texture, aroma, and flavor of the finished cheese. “Most of the flavor in cheese comes from the enzymatic breakdown of protein. First the bacteria convert lactose to lactic acid, then they go for the protein. The fat takes longer to break down, but it is eventually converted, too” (to short-chain fatty acids; some scientists contend that it is these fatty acids that contribute the majority of the flavor of a cheese, but others agree with Liam that it’s the conversion of protein to free amino acids that creates the yummy flavors we love so much). “The cheese flavors are dependent on what kind of starter bacteria you use, the type of rennet, the amount and kind of proteins in the milk, the type of sheep, the temperature of the milk, the moisture content of the cheese, the temperature of the ripening room, the strains of wild bacteria and yeasts that are in the milk, and the natural flora that’s on the equipment and around the dairy—it’s very complex and there’s no way to know all the variables. But we try for consistency,” Liam said.

First the 140 gallons of sheep’s milk went into the warming tank, where it was warmed to about 100ºF. While this was happening, Liam sanitized the cheesemaking tank with a chlorine and water solution. “Before electricity, people used to warm milk over a fire. They still do that in places like Sicily. Or they use the milk warm from the animal.”

Cindy Callahan came into the room to help with the actual cheesemaking. She’d been a nurse and then a lawyer in San Francisco, where her late husband, Ed, had been a physician. What started in 1990 as a little local cheesemaking operation soon became well known in the wine country. At first Bellwether cheeses were sold at farmers’ markets, and the Callahans got lots of enthusiastic, positive feedback about their cheese. “Now we’ve got a tiger by the tail with this business,” Cindy said. “We’ve filled every inch of this building. We’ve invested a lot of money in equipment. Do you realize how much cheese you have to make to support all this?” Despite her protestations, she’s obviously proud of Bellwether’s success.

The sheep’s milk was now pumped from the warming tank into the large tank up on the grillwork. “Now we add the starter culture,” Liam said, and tore open a foil package and shook the contents—a freeze-dried, cheese-colored powder that smelled like toast (Liam says like potato chips)—onto the surface of the glistening, creamy milk. It reminded me of the Vermeer painting of the kitchen maid pouring thick, creamy milk from a crockery pitcher into a bowl. The culture is a mesophilic culture called MM 100. It’s made in France and sold by the Dairy Connection, a supplier of cheesemaking cultures based in Middleton, Wisconsin. It contains three strains of lactococcus bacteria—

Lactococcus lactis

subsp.

lactis

,

Lactococcus lactis

subsp.

cremoris

, and

Lactococcus lactis

biovar

diacetylactis

. The first two are the main lactic acid–producing bacteria used by the cheese industry, whereas the latter strain adds aroma to the finished cheese. As Liam stirred the starter culture into the milk, he said that he keeps the temperature of the milk in the upper nineties, near one hundred, as it’s about to be made into cheese. “This is the upper range of the starter culture’s comfort,” he said. “Most cheesemakers who use the mesophilic culture keep their milk in the high eighties or lower nineties. I saw them doing it in Italy at the higher temperature, and it worked out fine. It’s worked out for us, too.”

We now had to wait twenty minutes before the coagulant would be added. Liam and the workers used the time to clean and wash the warming tank and hoses and wash down the floor.

Bellwether uses chymosin, the same enzyme as the rennet in calves’ stomachs. But actual calf rennet is not legally sold in the United States, and so the analog chymosin, laboratory-made, is used. Liam took a pipette and mixed exactly 70cc of pure chymosin in a quart of distilled water. “This is a powerful enzyme,” Liam said. “If I’d put it straight into the milk, it would immediately form a hard clump, so I have to dilute it. They make this enzyme in a laboratory, but I think the natural is better. In Sardinia, I saw them making the traditional cheese called Fiore Sardo. There was a bucket of salt on the farmhouse floor with calves’ stomachs in it. It had a distinct smell—not unpleasant but unique. Even though the cheese was aged and smoked for a month, I could taste in the cheese what I’d smelled in that bucket. Here in the States adding the coagulant is just a production step, but elsewhere it’s crucial to the flavor of the cheese. I don’t mind using chymosin, though. I think the milk flavors come through better.” He poured the diluted enzyme into the milk and quickly stirred it through the vat. “You can vary the amount of enzyme—more gives you a firmer curd, less gives a softer curd. But all three of our sheep’s milk cheeses will be made from this same vat. The difference comes from the ripening process and with our Pepato, the addition of peppercorns.”

We now had to wait for thirty minutes as the coagulant worked. I asked Liam what he does with the whey—the liquid that separates from the curd and is drained off. “We use that for ricotta,” he said. “We make ricotta from both sheep’s and cow’s milk whey—they’re very similar, although there’s a slight flavor difference. Ricotta was invented only a hundred years ago, you know. In Italy, they don’t make cow’s milk ricotta. They feel sheep’s milk is superior.” In Italy, whether whey goes to ricotta or not depends on the traditions of the place. Around Parma, Italy, for instance, whey from the making of the famous Parmigiano-Reggiano, one of the world’s great cheeses, is fed to the pigs that yield Parma hams and prosciutto, another of the world’s great foods.

“Ricotta isn’t hard to make,” Liam says. “We raise the temperature of the whey to 180 degrees, add salt, and acidify it with vinegar, then the solids precipitate out. We drain the solids and we’ve got ricotta.”

Ricotta,

by the way, is Italian for “recooked,” which is how the cheese is made.

While we were waiting for the chymosin to work, Liam and Cindy showed me the cold ripening room. Ripening rooms are used in lieu of caves in the earth, which naturally have the right conditions of temperature and humidity and are often used in places where cheesemaking is an ancient art and the caves were long ago devoted to ripening the local cheeses. The air in this ripening room was moist, the temperature was about 45 or 50ºF, and the wooden slat shelves were filled with round, inviting-looking, ripening cheeses. The youngest were creamy white. “These are our San Andreas and Pepatos,” Liam said. The San Andreas, named after the famous fault that caused the San Francisco quake of 1906 and which runs pretty much right under Bellwether Farms, is a smooth, full-flavored sheep’s milk cheese aged for two months. The Pepato is a similar cheese but with whole black peppercorns added. The oldest cheeses in the room, aged there for four months, were a dark gold. These were extra-aged Carmodys, named for the lane on which the farm is located, made from Jersey cow’s milk, with a smooth texture and a wonderful buttery flavor that Liam says is his take on the northern Italian Tomme. Much of the batch of milk that Liam was working with that day would be made into Toscano—a traditional hard Italian-style cheese aged four months, with nutty and fruity overtones to its strong buttery taste. In 1996, the American Cheese Society’s annual judging named Bellwether Toscano the Best Aged Sheep’s Milk Cheese in the country, and one taste tells you why.

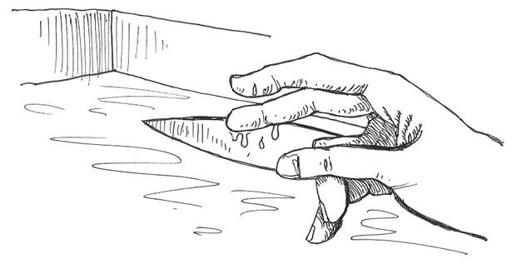

“That’s called a clean break.”

After thirty minutes, Liam and I climbed up on the grillwork and he patted the surface of the milk with the flat of his hand. It appeared rubbery, as though it had solidified. He took two fingers and slid them into the curd, then drew them up and out. The curd parted easily and cleanly and clear whey filled the slot he’d opened. “That’s called a clean break,” he said. “That’s what you look for. If the cheese isn’t set, the whey will still be milky.” He showed me another way to tell whether the curd is properly set. “Some cheesemakers do this.” He laid his hand, palm down and flat, on top of the curd where it met the vertical metal side of the vat. Exerting just a little sideways pressure, he moved his hand away from the metal side, gently pulling the curd from the metal. Again it came away cleanly, with clear whey in its wake.