The Eternal Flame (13 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Fiction

“Rocket fuel or rock, you win either way?” Carla was finding the whole thing amusing. “I can see the posters already.”

When they’d left the apartment, Carlo turned to her. “You think there’s a chance we’ll end up farming the Object?”

“Anything’s possible,” she said. “Though if the whole thing’s as inert as calmstone and we end up relying on it, the fuel problem won’t just be unsolved, it will be doubled.”

“Yeah.” As a child, when he’d first understood that the

Peerless

had been loaded up far beyond its capacity to return, Carlo had railed against the ancestors—and now here was Silvano, contemplating doing exactly the same thing. “Do you want to run for the Council on a No Expansion platform? ‘Forget about a bigger harvest, people! There’s no point getting used to a mountain of extra food, when we have no way to decelerate a mountain of extra rock!’”

Carla buzzed wryly. “Maybe not. I can’t really blame Silvano, though. He doesn’t want his son to have to do what he did.” When Carlo didn’t reply she glanced across at him. “Your solution would be better, but it’s harder for most of us to believe in. We all know that a flying mountain can be turned into a farm, but for well-fed women to start having two children sounds more like turning people into voles.”

“Western shrub voles, to be precise,” Carlo replied. “They’re the biparous ones. But they have no males, so that doesn’t really help—breeding still doubles their numbers. As far as anyone knows, there’s never been an animal population that was stable in the absence of predation, famine or disease.”

“Don’t get discouraged,” Carla said, reaching over and putting a hand on his shoulder. “That’s just the history of life for the last few eons. It’s not as if it’s a law of physics.”

14

T

amara woke in the clearing as the wheatlight was fading. She brushed the straw and petals off her body, then lay still for a while, luxuriating in the sensation of the soil against her skin. She was spoilt as a farmer’s co, she decided; she didn’t know how anyone could sleep in the near-weightlessness of the apartments. She’d never had any trouble doing her work in the observatory, and she often spent the whole day close to the axis, but having to be held in place by a tarpaulin every night, trying to cool yourself in an artificial bed’s sterile sand, struck her as the most miserable recipe for insomnia imaginable.

She rose to her feet and looked around. Tamaro was standing a short distance away; her father was up, but she couldn’t see him.

“Good morning,” Tamaro said. He seemed distracted, the greeting no more than a formality.

“Good morning.” Tamara stretched lazily and turned her face to the ceiling. Above them, the moss was waking; in the corridors the same species shone ceaselessly, but here it had learned to defer to the wheat. “Have you been up long?”

“A lapse or two,” he replied.

“Oh.” She’d half-woken much earlier and thought she’d sensed his absence—in the yielding of the scythe when she’d brushed an arm against it—but she hadn’t opened her eyes to check. “I should get moving,” she said. She had no urgent business to attend to, but when Tamaro was distant like this it usually meant that he was hoping she’d leave soon, allowing him to eat an early breakfast. That was probably what her father was doing right now.

He said, “Can I talk to you first?”

“Of course.” Tamara walked over to him.

“I heard about Massima,” he said.

“Yeah, that was a shame.”

“You never mentioned it.”

Tamara buzzed curtly. “It wasn’t that much of a shame. I would have been happy to have her with us, but it won’t affect the mission.”

Tamaro said, “She must have decided that it wasn’t worth the risk.”

“Well, that was her right.” Tamara was annoyed now. Did he really think he could compare her to Massima? “Since she was only ever going to be a spectator, I don’t blame her for setting such a low threshold.”

“Do I have to beg you not to go?” he asked her. He sounded hurt now. “Have you even thought about what it would mean to me, if something happened to you?”

Tamara reached down and squeezed his shoulder reassuringly. “Of course I have. But I’ll be careful, I promise.” She tried to think back to what Ada had said, the way of putting it that had won over her own co. “We were born too late to share the thrill of the launch, and too early to take part in the return. If I turn down an opportunity like this, what’s my life for? Just waiting around until we have children?”

“Did I ever put pressure on you to have children?” Tamaro demanded indignantly.

“That’s not what I meant.”

“I’ve always been happy for you to work!” he said. “You won’t hear a word of complaint from me, just so long as you do something safe.”

Tamara struggled to be patient. “You’re not listening. I need to do

this

. Part of it’s the chance to help the chemists fix the fuel problem—and that in itself would be no small thing. But flying the

Gnat

is the perfect job for me: for my skills, my temperament, my passions. If I’d had to spend my life watching rocks like this pass by in the distance, I would have made the best of it. But

this

is a chance to do everything I’m capable of.”

Tamaro said coldly, “And you’d risk our children, for that?”

“Oh…” Tamara was angry now; she’d never imagined he’d resort to anything so cheap. “If I die out there, you’ll find yourself a nice widow soon enough. I know most of them have sold their own entitlements, but you’ll have mine, won’t you? You’ll be the definition of an irresistible co-stead.”

“You think this is a joke?” Tamaro was furious.

“How was I joking? It’s the truth: if I die, you’ll still get to be a father. So stop sulking about it, as if you have more at stake here than I do.”

He stepped away from her, visibly revolted. “I’m not fathering children with someone else,” he said. “The flesh of our mother is the flesh of my children; however long you might borrow it, it’s not yours. Least of all yours to endanger.”

Tamara buzzed with derision. “What age are you living in? I can’t even look at you, you buffoon!” She pushed past him onto the path and headed out of the clearing, half expecting him to start following her and haranguing her, but each time she stole a glance with her rear gaze he was still standing motionless where she’d left him.

When he vanished from sight behind a bend in the path, Tamara felt a strange, vertiginous thrill.

Was she leaving him?

At the very least, she wouldn’t be coming back to the farm until he sought her out and apologized. She could sleep in the office next to the observatory—in a bed without gravity, but she’d survive.

As she strode along between the dormant wheat-flowers, she began to feel a twinge of guilt. She wanted Tamaro to understand what the

Gnat

meant to her, but she didn’t want to bludgeon him into acquiescence. If he was afraid of losing his chance to be a father, the threat of desertion would be even more distressing than the prospect of her death: her children, not his, would inherit the family’s entitlement. What kind of fate was she prepared to force upon him? The choice between a lonely death and… what? Hiding the children he had with some widow? Stealing grain for them from his own crops, until the auditors finally caught him? He needed to grow up and accept her autonomy, but there were limits to how ruthless she was willing to be. She still loved him, she still wanted him to raise their children. Whatever they’d both said in the heat of the moment, she couldn’t imagine anything changing that.

Tamara thought of turning back and trying to effect a speedy reconciliation, but then she stiffened her resolve. It would be painful for both of them to pass the day with this quarrel hanging over them, but she had to let Tamaro feel the sting of it. Maybe their father would talk some sense into him. As often as he’d taken Tamaro’s side, Erminio knew how stubborn his daughter could be. If he’d overheard the morning’s conversation, what counsel could he offer his son but acceptance?

She came to the farm’s exit and seized the handle of the door in front of her without slowing her pace. The handle turned a fraction then stuck; she walked straight into the door, pinning her outstretched arm between the slab of calmstone and her advancing torso.

She cursed and stepped back, waited for the pain in her arm to subside, then tried the handle again. On the fourth attempt she understood: it wasn’t stuck. The door was locked.

The last time she’d seen the key, she’d been a child. Her father had shown her where it was kept in one of the store-holes, a tool to be wielded against fanciful threats that sounded like stories out of the sagas: rampaging arborines who’d escaped from the forest to conquer the

Peerless

, or rampaging mobs driven mad by hunger, coming to strip the grain from the fields.

It was possible, just barely, that Tamaro had run ahead of her by another route. But he would have had to cut through the fields, and he could not have done it silently.

So either he’d locked the door before she’d even risen that morning, before they’d exchanged a word, or Erminio really had been listening to them—and far from resolving to plead her case with Tamaro, he’d decided that the way to fix this problem was to keep her on the farm by force.

“You arrogant pieces of shit!” Tamara hoped that at least one of them was lurking nearby to overhear her.

Angry as she was, she was struck by one ground for amusement and relief:

better that they try this stunt now than on the launch day.

If they’d caught her by surprise at the crucial time it would not have been hard to keep her confined for a few bells. Once she’d failed to show up, Ada and Ivo would have had no choice but to leave without her, and her idiot family would have got exactly what they’d wanted. But apparently they couldn’t bear to defer the pleasure of punishing her.

Tamaro was coming down the path toward her.

“Where’s the key?” she demanded.

“Our father’s taken it.” He nodded toward the door, implying that Erminio was outside, beyond her reach.

“So what’s the plan?”

“I gave you chance after chance,” he said. “But you wouldn’t listen.” He didn’t sound angry; his voice was dull, resigned.

“What do you think is going to happen?” she asked. “Do you know how many people are expecting me to turn up for meetings in the next three days alone? Out of all those friends and colleagues, I promise you someone will come looking for me.”

“Not after they hear the happy news.”

Tamara stared at him. If Erminio was out there telling people that she’d given birth, this had gone beyond a private family matter. She couldn’t just forgive her captors and walk away, promising her silence, when the very fact of her survival would show them up as liars.

“I’ve burned all your holin,” Tamaro told her. “You know I’d never try to force myself on you, but what happens now is your choice.”

She searched his face, looking for a hint of uncertainty—if not in the rightness of his goals, in his chance of achieving them. But the man she’d loved since her first memory of life seemed convinced that there were only two ways this could end.

Either she’d agree to let him trigger her, and she’d give birth to his children—taking comfort in the knowledge that he’d promised himself to them.

Or she’d stay here, without holin, until her own body betrayed her. She’d give birth alone, and her sole victory would be to have cheated her jailer and her children alike of the bond that would have allowed them to thrive.

15

T

he hiss from the sunstone lamp rose in pitch to an almost comical squeak. Carla could hear the remaining pellets of fuel ricocheting around the crucible, small enough now that the slightest asymmetry in the hot gas erupting from their surface turned them into tiny rockets. A moment later they’d burned away completely and the lamp was dark and silent.

Onesto walked over to the firestone lamp and turned it up, then went back to his desk.

The workshop looked drab in the ordinary light. Carla punctured the seal of the evacuated container, waited for the air to leak in, then tore away the seal and retrieved the mirror. After she’d inspected it herself she handed it to Patrizia, who surveyed it glumly.

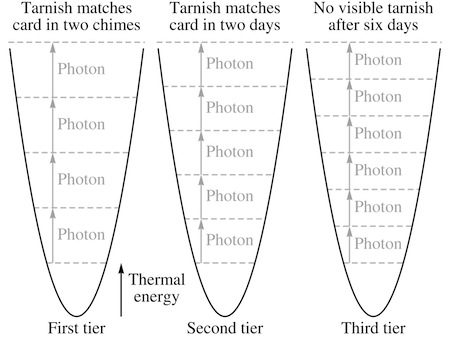

It had been obvious for the last few days that the tarnishing wasn’t proceeding in the manner they’d predicted. The first tier had matched the reference card placed beside the mirror after a mere two chimes’ exposure; the second tier had taken two days. That alone showed that the time to create each photon couldn’t be the same in each case. But Patrizia’s idea that the time might be proportional to the period of the light couldn’t explain what they were seeing, either. For two near-identical hues on either side of the border between the second and third tiers, the period of the light was virtually the same—but while the fifth photon needed to complete the tarnishing reaction in the second tier had only taken two days to appear, after waiting more than twice as long for one more photon, the third tier remained pristine.

Carla sketched the results on her chest. “The photon theory can explain the frequencies where we switch from one tier to the next. But how do we make sense of the timing?”