The Eternal Flame (45 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Fiction

“I’m too tired for anything else,” Carla admitted. The news that Carlo’s best attempts to end the famine now involved the prospect of inserting signals from a mating arborine into women’s bodies had crushed whatever small hope she’d once had that she might free herself from the hunger daze. “Maybe someone will look at the rebounder again when the politics is right.”

“Forget about the politics,” Patrizia said blithely. “You won’t need to go begging for sunstone if you can make this work in an ordinary solid.”

“We’ve looked at every kind of clearstone in the mountain,” Carla protested. “Are you going to try cooking up something new?”

“Not exactly,” Patrizia replied. “But I just read Assunto’s paper on multi-particle waves and the Rule of One.”

Carla hesitated, turning the non sequitur over in her mind in the hope that a connection would become apparent.

It didn’t.

“Go on,” she said.

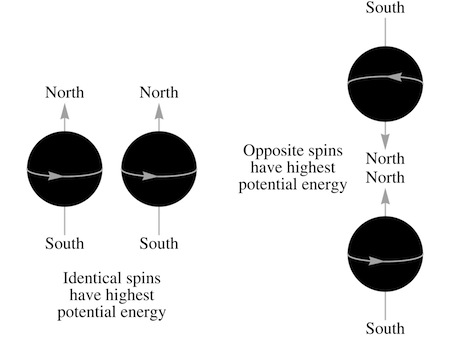

“According to Nereo’s theory,” Patrizia began, “if you take two tiny spheres with source strength and set them spinning, one beside the other, if the ‘north poles’ are sufficiently close they’ll try to repel each other. That means the system will have its highest potential energy if you force those poles together. The circumstances in which that happens will depend on both the directions in which the spheres are spinning and their relative positions.”

She sketched two examples.

“It’s an odd effect, isn’t it?” Carla mused. “Two positive sources attract, close up, but the poles of these spheres work the other way: like repels like.”

“It’s strange,” Patrizia agreed. “And I can’t claim that it’s ever been verified directly. Still, everything we know suggests that it’s true—and that it ought to apply to spinning luxagens, in addition to the usual attractive force.”

Carla said, “I wouldn’t argue with that.” They’d found that the energy of a single luxagen in a suitably polarized field depended on its spin, and there was no reason to think that the analogy would suddenly break down when it came to two spinning luxagens side by side.

Patrizia continued. “The Rule of One won’t let you have two luxagens with identical waves and the same spin—but that still leaves open the question of what happens to the spin when the waves themselves are different. If you take this pole-to-pole repulsion into account for two luxagen waves in the energy valley of a solid, on average it gives a higher potential energy when the spins are identical. So if the spins start out being different the system will emit a photon and gain the energy to flip one of the spins and make them the same. In other words, though the paired luxagens with identically shaped waves

must

have opposite spins, the unpaired ones ought to end up with their spins aligned!”

Carla wasn’t sure where this was heading. “The energy differences from these pole-to-pole interactions would be very small, and we probably don’t have the wave shapes exactly right. Do you really think this is a robust conclusion?”

Patrizia said, “I don’t, which is why I didn’t raise it with you before. But then I read Assunto’s explanation for the Rule of One, and that changes everything.”

“It ruins the effect?”

“No,” Patrizia replied. “It strengthens it enormously!”

Carla was bewildered. “How?”

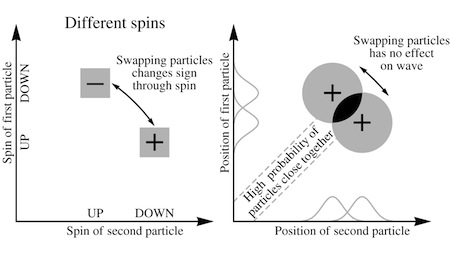

Patrizia buzzed with delight. “This is the beautiful part. Assunto claims that for any pair of luxagens we need the overall description to

change sign

if we swap the particles. If the spins are identical, in order to satisfy that rule you need to subtract the swapped versions of the waves. But if the spins are different, you use the spins

instead of

the waves to do the job of changing the overall sign when you swap the particles. So in that case, you find the positions of the luxagens by

adding

the swapped versions of the waves.”

She sketched an example.

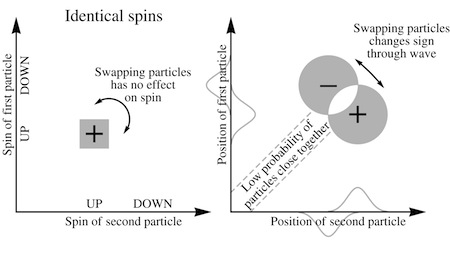

“By adding the waves,” she said, “you end up with a high probability of the luxagens being close to each other. Now compare that with the case where the spins are the same and you need to subtract the waves to get the change of sign. There’s a much lower probability of the luxagens coming close.”

“All from the spins,” Carla marveled. “And by changing the distance between the luxagens…”

“You change their potential energy,” Patrizia concluded. “Not from the weak, pole-to-pole repulsion, but from the attractive force between the luxagens. Through Assunto’s rule, having identical spins forces the average distance between the luxagens to be greater, which means a higher potential energy. So we’re back at the original conclusion: unpaired luxagens really

should

be spinning in the same direction.”

Carla paused and ran through the whole analysis again in her head; there were just enough twists in the argument that she was afraid they might have lost track of one of them and proved the opposite of what they’d thought they’d proved. “That does makes sense,” she concluded. “But what does it have to do with the rebounder?”

Patrizia said, “In an optical solid we could use the polarization of the light to create the kind of field where each luxagen’s spin affects its energy—splitting the usual energy levels by a very small amount. The tiny jump between those closely spaced levels would be a perfect match for the tiny shift in energy for photons rebounding from an imperfect mirror. I’m sure we could have made that work—but wouldn’t it be better to do it in an ordinary solid?”

Carla understood the connection now. “Enough luxagens all spinning in the same direction ought to produce a similar kind of polarized field within an ordinary solid. But we never saw any sign of it in the spectra of the clearstone samples.”

Patrizia adjusted her grip on the rope. “The spins

within each valley

ought to be aligned—but once you go any further, the waves overlap far less and the force between the luxagens starts cycling back and forth between attraction and repulsion. So we can’t rely on Assunto’s rule to produce any kind of long-range order. Beyond a certain point, the directions of the spins will just vary at random—producing fields with random polarizations that largely cancel each other out.”

“Right.” Carla hesitated. “Which is unfortunate, but what can we actually do about it?”

“Maybe nothing,” Patrizia conceded. “But there’s one thing we could try. If the geometry, the energy levels and the number of unpaired luxagens are all favorable… I think we could ‘imprint’ the regularity of an optical solid onto a real solid. The field pattern traveling through the optical solids we’ve made so far isn’t moving all that rapidly. There’s no reason we couldn’t shoot a real solid through the light field at the same speed; that way it would experience a fixed pattern. If we can expose the material to an ordered, polarized field for long enough, we might be able to achieve a long-range alignment between all the unpaired spins.”

Carla was speechless. Patrizia had produced her share of follies—and it was possible that this was one of them—but nobody else on the

Peerless

could have thought up this magnificent, audacious scheme.

“If we can identify a good candidate for imprinting,” Patrizia continued, “the hard part will be obtaining flawless crystals. This can only work if the geometry is almost perfect, otherwise the fields from the luxagens in different valleys will slip out of phase. But if we start with small granules, and pick out the ones that look homogeneous—”

“Like Sabino when he measured Nereo’s force?” Carla interjected.

“Exactly.” Patrizia was growing anxious to hear a verdict. “So you agree that it’s worth trying?”

Carla said cautiously, “I can’t see anything that rules it out. But we need to look at the whole thing more closely; we need to study the dynamics of these unpaired luxagens in an external field—”

Patrizia gave a triumphant chirp. “When do we start?”

Carla had no more classes to teach for the day, and she doubted she’d be able to concentrate on anything else until it was clear whether or not this offered a real chance to salvage the rebounder. “What’s wrong with now?”

A woman called out brusquely from the doorway, “Do you know where Carlo is?” It was his colleague, Amanda.

“Not this instant,” Carla replied. “He said he was going to see Silvano this morning, but the meeting’s probably over by now.”

Amanda said, “You need to find him.”

She wasn’t being rude, Carla realized. She was distressed.

“What’s going on?” Carla asked her gently.

“Some men tried to grab me outside my apartment,” Amanda replied. “And now I can’t find Macaria or Carlo anywhere.”

“What men?”

“There were four of them, all wearing masks. Someone helped me fight them off, then they ran away.”

Carla felt her whole body grow tense. “You think this is about the arborine experiments?”

Amanda said, “Yes.”

Patrizia turned to Carla. “I heard people talking about that this morning. I thought it was nonsense, I just ignored it.”

“What were they saying?”

“That Carlo had created an influence that could force women to give birth.” Patrizia’s tone was scornful. “All he had to do was point a light at your skin!”

“That’s not true,” Amanda assured her. She gave a quick account of the actual procedure.

Patrizia looked dazed. “You’re saying I could have a child and

go on living?

”

“We’ve only tested it on arborines,” Amanda stressed.

“But once you’re sure that it works on people—?”

“It still won’t be a simple thing,” Amanda replied. “It would require surgery before and after the birth.”

“And the number of children?” Patrizia asked her.

Amanda said, “One. Always one at a time.”

Carla broke in. “I should go and see Silvano, and try to retrace Carlo’s movements from there.”

“I’ll come with you,” Amanda offered.

“What about Macaria?”

“I’ve already spoken to her co. He’s gathered some friends and started his own search.”

“I’ll come too,” Patrizia said. “Until we find Carlo, my hands are your hands.”

Carla was moved by this vow of solidarity, but as they headed out into the corridor she realized that it came from something more than friendship. Patrizia was not at all dismayed by what Carlo had done. Once the shock had worn off she had shown every sign of welcoming the news.

There were women who would embrace this bizarre intervention.

Carlo was not in danger from some confused rabble who’d taken the rumors Patrizia had heard seriously. He was in danger from every man who’d heard the truth about the technology, and feared that his co would use it to dispense with him entirely.

“Carlo hasn’t been here,” Silvano insisted, turning to shout a curt reprimand into the children’s room. “What’s this about?”

Carla let Amanda explain most of it: the arborine experiments, Tosco’s reaction, the attempt to abduct her, her two missing colleagues. Silvano took the first revelation with admirable poise, but Carla judged that he was not quite so unfazed as to be hiding prior knowledge of the matter.

Patrizia recounted the rumors she’d heard of a new influence. Silvano seemed paralyzed for a moment, but then he said, “I’m going to call an emergency meeting of the Council. I’ll ask both Tosco and Amanda to give evidence, so we get both sides of this.” He must have seen the growing distress on Carla’s face; he said, “I’m sure we’ll find Carlo unharmed, very soon. You should put a report out through the relay. What the Council can do is promulgate statements dismissing the rumors, and warning people against taking any kind of action against the researchers.”