The Eyes of the Dragon (11 page)

Read The Eyes of the Dragon Online

Authors: Stephen King

“My fathers's

name

!” Thomas gasped.

name

!” Thomas gasped.

“Oh, that's nothing! Look over here! Pirate treasure, Tommy!”

He showed Thomas a pile of booty from the encounter with the Anduan pirates some twelve years ago. The Delain Treasury was rich, the few treasureroom clerks old, and this particular heap hadn't been sorted yet. Thomas gasped at heavy swords with jeweled hilts, daggers with blades that had been crusted with serrated diamonds so they would cut deeper, heavy killballs made of rhodochrosite.

“All this belongs to the Kingdom?” Thomas asked in an awed voice.

“It all belongs to your

father

,” Flagg replied, although Thomas had actually been correct. “Someday it will all belong to Peter.”

father

,” Flagg replied, although Thomas had actually been correct. “Someday it will all belong to Peter.”

“And me,” Thomas said with a ten-year-old's confidence.

“No,” Flagg said, just the right tinge of regret in his voice, “just to Peter. Because he's the oldest, and he'll be King.”

“He'll share,” Thomas said, but with the slightest tremor of doubt in his voice. “Pete

always

shares.”

always

shares.”

“Peter's a fine boy, and I'm sure you're right. He'll

probably

share. But no one can

make

a King share, you know. No one can

make

a King do anything he doesn't want to do.” He looked at Thomas to gauge the effect of this remark, then looked back at the deep, shadowy treasure room. Somewhere, one of the aged clerks was droning out a count of ducats. “Such a lot of treasure, and all for one man,” Flagg remarked. “It's really something to think about, isn't it, Tommy?”

probably

share. But no one can

make

a King share, you know. No one can

make

a King do anything he doesn't want to do.” He looked at Thomas to gauge the effect of this remark, then looked back at the deep, shadowy treasure room. Somewhere, one of the aged clerks was droning out a count of ducats. “Such a lot of treasure, and all for one man,” Flagg remarked. “It's really something to think about, isn't it, Tommy?”

Thomas said nothing, but Flagg had been well pleased. He saw that Tommy

was

thinking about it, all right, and he judged that another of those poisoned caskets was tumbling down into the well of Thomas's mindâ

ker

-

splash!

And that was indeed so. Later, when Peter proposed to Thomas that they share the expense of the nightly bottle of wine, Thomas had remembered the great treasure roomâand he remembered that all the treasure in it would belong to his brother.

Easy for you to talk so blithely of buying wine! Why not? Someday you'll have all the money in the world!

was

thinking about it, all right, and he judged that another of those poisoned caskets was tumbling down into the well of Thomas's mindâ

ker

-

splash!

And that was indeed so. Later, when Peter proposed to Thomas that they share the expense of the nightly bottle of wine, Thomas had remembered the great treasure roomâand he remembered that all the treasure in it would belong to his brother.

Easy for you to talk so blithely of buying wine! Why not? Someday you'll have all the money in the world!

Then, about a year before he brought the poisoned wine to the King, on impulse, Flagg had shown Thomas this secret passage . . . and on this one occasion his usually unerring instinct for mischief might have led him astray. Again, I leave it for you to decide.

26

T

ommy, you look down in the dumps!” he cried. The hood of his cloak was pushed back on that day, and he looked almost normal.

ommy, you look down in the dumps!” he cried. The hood of his cloak was pushed back on that day, and he looked almost normal.

Almost.

Tommy

felt

down in them. He had suffered through a long luncheon at which his father had praised Peter's scores in geometry and navigation to his advisors with the most lavish superlatives. Roland had never rightly understood either. He knew that a triangle had three sides and a square had four; he knew you could find your way out of the woods when you were lost by following Old Star in the sky; and that was where his knowledge ended. That was where Thomas's knowledge ended, too, so he felt that luncheon would never be done. Worse, the meat was just the way his father liked itâbloody and barely cooked. Bloody meat made Thomas feel almost sick.

felt

down in them. He had suffered through a long luncheon at which his father had praised Peter's scores in geometry and navigation to his advisors with the most lavish superlatives. Roland had never rightly understood either. He knew that a triangle had three sides and a square had four; he knew you could find your way out of the woods when you were lost by following Old Star in the sky; and that was where his knowledge ended. That was where Thomas's knowledge ended, too, so he felt that luncheon would never be done. Worse, the meat was just the way his father liked itâbloody and barely cooked. Bloody meat made Thomas feel almost sick.

“My lunch didn't agree with me, that's all,” he said to Flagg.

“Well, I know just the thing to cheer you up,” Flagg said. “I'll show you a secret of the castle, Tommy my boy.”

Thomas was playing with a buggerlug bug. He had it on his desk and had set his schoolbooks around it in a series of barriers. If the trundling beetle looked as if he might find a way out, Thomas would shift one of the books to keep him in.

“I'm pretty tired,” Thomas said. This was not a lie. Hearing Peter praised so highly always made him feel tired.

“You'll like it,” Flagg said in a tone that was mostly wheedling . . . but a little threatening, too.

Thomas looked at him apprehensively. “There aren't any . . . any bats, are there?”

Flagg laughed cheerilyâbut that laugh raised gooseflesh on Thomas's arms anyway. He clapped Thomas on the back. “Not a bat! Not a drip! Not a draft! Warm as toast! And you can peek at your father, Tommy!”

Thomas knew that peeking was just another way of saying spying, and that spying was wrongâbut this had been a shrewd shot all the same. This next time the buggerlug bug found a way to escape between two of the books, Thomas let it go. “All right,” he said, “but there better not be any bats.”

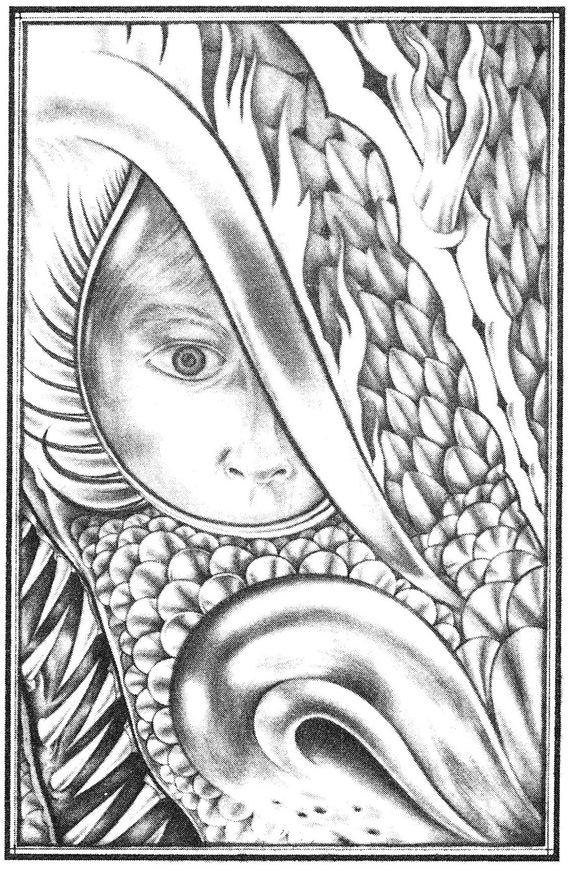

Flagg slipped an arm around the boy's shoulders. “No bats, I swearâbut here's something for you to mull over in your mind, Tommy. You'll not only see your father, you'll see him through the eyes of his greatest trophy.”

Thomas's own eyes widened with interest. Flagg was satisfied. The fish was hooked and landed. “What do you mean?”

“Come and see for yourself,” was all he would say.

He led Thomas through a maze of corridors. You would have become lost very soon, and I probably would have gotten lost myself before long, but Thomas knew this way as well as you know your way through your own bedroom in the darkâat least he did until Flagg led him aside.

They had almost reached the King's own apartments when Flagg pushed open a recessed wooden door that Thomas had never really noticed before. Of course it had always been there, but in castles there are often doorsâwhole wings, evenâthat have mastered the art of being

dim.

dim.

This passage was quite narrow. A chambermaid with an armload of sheets passed them; she was so terrified to have met the King's magician in this slim stone throat that it seemed she would happily have shrunk into the very pores of the stone blocks to avoid touching him. Thomas almost laughed because sometimes he felt a little like that himself when Flagg was around. They met no one else at all.

Faintly, from below them, he could hear dogs barking, and that gave him a rough idea of where he was. The only dogs inside the castle proper were his father's hunting dogs, and they were probably barking because it was time for them to be fed. Most of Roland's dogs were now almost as old as he was, and because he knew how the cold ached in his own bones, Roland had commanded that a kennel be made for them right here in the castle. To reach the dogs from his father's main sitting chamber, one went down a flight of stairs, turned right, and walked ten yards or so up an interior corridor. So Thomas knew they were about thirty feet to the right of his father's private rooms.

Flagg stopped so suddenly that Thomas almost ran into him. The magician looked swiftly around to make sure they had the passageway to themselves. They did.

“Fourth stone up from the one at the bottom with the chip in it,” Flagg said. “Press it. Quick!”

Ah, there was a secret here, all right, and Thomas loved secrets. Brightening, he counted up four stones from the one with the chip and pressed. He expected some neat little bit of jiggerypokeryâa sliding panel, perhapsâbut he was quite unprepared for what did happen.

The stone slid in with perfect ease to a depth of about three inches. There was a click. An entire section of wall suddenly swung inward, revealing a dark vertical crack. This wasn't a wall at all! It was a huge door! Thomas's jaw dropped.

Flagg slapped Thomas's bottom.

“Quick, I said, you little fool!” he cried in a low voice. There was urgency in his voice, and this wasn't simply put on for Thomas's benefit, as many of Flagg's emotions were. He looked right and left to verify that the passage was still empty. “Go! Now!”

Thomas looked at the dark crack that had been revealed and thought uneasily about bats again. But one look at Flagg's face showed him that this would be a bad time to attempt a discussion on the subject.

He pushed the door open wider and stepped into the darkness. Flagg followed at once. Thomas heard the low flap of the magician's cloak as he turned and shoved the wall closed again. The darkness was utter and complete, the air still and dry. Before he could open his mouth to say anything, the blue flame at the tip of Flagg's index finger flared alight, throwing a harsh blue-white fan of illumination.

Thomas cringed without even thinking about it, and his hands flew up.

Flagg laughed harshly. “No bats, Tommy. Didn't I promise?”

Nor were there. The ceiling was quite low, and Thomas could see for himself. No bats, and warm as toast . . . just as the magician had promised. By the light of Flagg's magic finger-flare, he could also see they were in a secret passage which was about twenty-five feet long. Walls, floor, and ceiling were covered with ironwood boards. He couldn't see the far end very well, but it looked perfectly blank.

He could still hear the muffled barking of the dogs.

“When I said be quick, I meant it,” Flagg said. He bent over Thomas, a vague, looming shadow that was, in this darkness, rather batlike itself. Thomas drew back a step, uneasily. As always, there was an unpleasant smell about the magicianâa smell of secret powders and bitter herbs. “You know where the passage is now, and I'll not be the one to tell you not to use it. But if you're ever

caught

using it, you must say you discovered it by accident.”

caught

using it, you must say you discovered it by accident.”

The shape loomed even closer, forcing Thomas back another step.

“If you say

I

showed it to you, Tommy, I'll make you sorry.”

I

showed it to you, Tommy, I'll make you sorry.”

“I'll never tell,” Thomas said. His words sounded thin and shaky.

“Good. Better yet if no one ever sees you using it. Spying on a King is serious business, prince or not. Now follow me. And be quiet.”

Flagg led him to the end of the passageway. The far wall was also dressed with ironwood, but when Flagg raised the flame that burned from the tip of his finger, Thomas saw two little panels. Flagg pursed his lips and blew out the light.

In utter blackness, he whispered: “Never open these two panels with a light burning. He might see. He's old, but he still sees well. He might see something, even though the eyeballs are of tinted glass.”

“Whatâ”

“

Shhhh!

There isn't much wrong with his ears, either.”

Shhhh!

There isn't much wrong with his ears, either.”

Thomas fell quiet, his heart pounding in his chest. He felt a great excitement that he didn't understand. Later he thought that he had been excited because he knew in some way what was going to happen.

In the darkness he heard a faint sliding sound, and suddenly a dim ray of lightâtorchlightâlit the darkness. There was a second sliding sound and a second ray of light appeared. Now he could see Flagg again, very faintly, and his own hands when he held them up before him.

Thomas saw Flagg step up to the wall and bend a little; then most of the light was cut out as he put his eyes to the two holes through which the rays of light fell. He looked for a moment, then grunted and stepped away. He motioned to Thomas. “Have a look,” he said.

More excited than ever, Thomas cautiously put his eyes to the holes. He saw clearly enough, although everything had an odd greenish-yellow aspectâit was as if he were looking through smoked glass. A sense of perfect, delighted wonder rose in him. He was looking down into his father's sitting room. He saw his father slouched by the fire in his favorite chairâone with high wings which threw shadows across his lined face.

It was very much the room of a huntsman; in our world such a room would often be called a den, although this one was as big as some ordinary houses. Flaring torches lined the long walls. Heads were mounted everywhere: heads of bear, of deer, of elk, of wildebeest, of cormorant. There was even a grand featherex, which is the cousin of our legendary bird the phoenix. Thomas could not see the head of Niner, the dragon his father had killed before he was born, but this did not immediately register on him.

His father was picking morosely at a sweet. A pot of tea steamed near at hand.

That was all that was really happening in that great room that could have (and at times had) held upward of two hundred peopleâjust his father, with a fur robe draped around him, having a solitary afternoon tea. Yet Thomas watched for a time that seemed endless. His fascination and his excitement with this view of his father cannot be told. His heartbeat, which had been rapid before, doubled. Blood sang and pounded in his head. His hands clenched into fists so tight that he would later discover bloody crescent moons imprinted into his palms where his fingernails had bitten.

Why was he so excited simply to be looking at an old man picking halfheartedly at a piece of cake? Well, first you must remember that the old man wasn't just

any

old man. He was Thomas's father. And spying, sad to say, has its own attraction. When you can see people doing something and they don't see you, even the most trivial actions seem important.

any

old man. He was Thomas's father. And spying, sad to say, has its own attraction. When you can see people doing something and they don't see you, even the most trivial actions seem important.

Other books

Lake Overturn by Vestal McIntyre

The Gunsmith 385 by J. R. Roberts

Elias (New Adult Romance) (West Bend Saints Book 1) by Paige, Sabrina

The Destiny (Blood and Destiny Book 4) by E.C. Jarvis

The Swap by Antony Moore

High Octane by Lisa Renee Jones

The Divine Invasion by Philip K. Dick

Salt by Mark Kurlansky

Greed: A Detective John Lynch Thriller by O'Shea, Dan

Play With You (Loneliness) by Cole, Alison