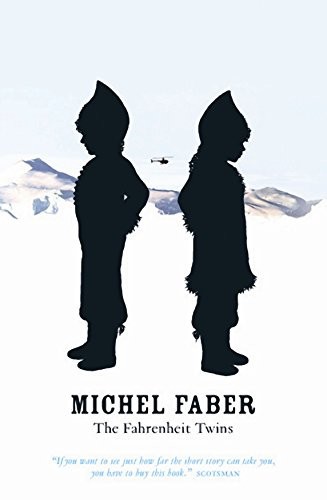

The Fahrenheit Twins

Read The Fahrenheit Twins Online

Authors: Michel Faber

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Literary

THE FAHRENHEIT

TWINS

Michel Faber

As always, I thank my dear Eva for her criticism and wise advice

during the revision of these stories

.

CONTENTS

THE SAFEHOUSE

I

I wake up, blinking hard against the sky, and the first thing I remember is that my wife cannot forgive me. Never, ever.

Then I remind myself I don’t have a wife anymore.

Instead, I’m lying at the bottom of a stairwell, thirty concrete steps below street level in a city far from my home. My home is in the past, and I must live in the present.

I’m lying on a soft pile of rubbish bags, and I seem to have got myself covered in muck. It’s all over my shabby green raincoat and the frayed sleeves of my jumper, and there’s a bit on my trousers as well. I sniff it, trying to decide what it is, but I can’t be sure.

How strange I didn’t notice it when I was checking this place out last night. OK, it was already dark by then and I was desperate to find somewhere to doss down after being moved on twice already. But I remember crawling into the rubbish really carefully, prodding the bin bags with my hands and thinking this was the softest and driest bed I was likely to find. Maybe the muck seeped out later on, under pressure from my sleeping body.

I look around for something to wipe my clothes with. There’s nothing, really. If I were a cat, I’d lick the crap off with my tongue, and still be a proud, even fussy creature. But I’m not a cat. I’m a human being.

So, I pull a crumpled-up advertising brochure out of the trash, wet it with dregs from a beer bottle, and start to scrub my jacket vigorously with the damp wad of paper.

Maybe it’s the exercise, or maybe the rising sun, but pretty soon I feel I can probably get by without these dirty clothes – at least until tonight. And tonight is too far away to think about.

I stand up, leaving my raincoat and jumper lying in the garbage, where they look as if they belong anyway. I’m left with a big white T-shirt on, my wrinkled neck and skinny arms bare, which feels just right for the temperature. The T-shirt’s got writing on the front, but I’ve forgotten what the writing says. In fact, I can’t remember where I got this T-shirt, whether someone gave it to me or I stole it or even bought it, long long ago.

I climb the stone steps back up to the street, and start walking along the footpath in no particular direction, just trying to become part of the picture generally. The big picture. Sometimes in magazines you see a photograph of a street full of people, an aerial view. Everyone looks as though they belong, even the blurry ones.

I figure it must be quite early, because although there’s lots of traffic on the road, there’s hardly any pedestrians. Some of the shops haven’t opened yet, unless it’s a Sunday and they aren’t supposed to. So there’s my first task: working out what day it is. It’s good to have something to get on with.

Pretty soon, though, I lose my concentration on this little mission. There’s something wrong with the world today, something that puts me on edge.

It’s to do with the pedestrians. As they pass by me on the footpath, they look at me with extreme suspicion – as if they’re thinking of reporting me to the police, even though I’ve taken my dirty clothes off to avoid offending them. Maybe my being in short sleeves is the problem. Everyone except me seems to be wrapped up in lots of clothes, as though it’s much colder than I think it is. I guess I’ve become a hard man.

I smile, trying to reassure everybody, everybody in the world.

Outside the railway station, I score half a sandwich from a litter bin. I can’t taste much, but from the texture I can tell it’s OK – not slimy or off. Rubbish removal is more regular outside the station than in some other places.

A policeman starts walking towards me, and I run away. In my haste I almost bump into a woman with a pram, and she hunches over her baby as if she’s scared I’m going to fall on it and crush it to death. I get my balance back and apologise; she says ‘No harm done,’ but then she looks me over and doesn’t seem so sure.

By ten o’clock, I’ve been stopped in the street three times already, by people who say they want to help me.

One is a middle-aged lady with a black woollen coat and a red scarf, another is an Asian man who comes running out of a newsagent’s, and one is just a kid. But they aren’t offering me food or a place to sleep. They want to hand me over to the police. Each of them seems to know me, even though I’ve never met them before. They call me by name, and say my wife must be worried about me.

I could try to tell them I don’t have a wife anymore, but it’s easier just to run away. The middle-aged lady is on high heels, and the Asian man can’t leave his shop. The kid sprints after me for a few seconds, but he gives up when I leap across the road.

I can’t figure out why all these people are taking such an interest in me. Until today, everyone would just look right through me as if I didn’t exist. All this time I’ve been the Invisible Man, now suddenly I’m everybody’s long-lost uncle.

I decide it has to be the T-shirt.

I stop in front of a shop window and try to read what the T-shirt says by squinting at my reflection in the glass. I’m not so good at reading backwards, plus there’s a surprising amount of text, about fifteen sentences. But I can read enough to tell that my name is spelled out clearly, as well as the place I used to live, and even a telephone number to call. I look up at my face, my mouth is hanging open. I can’t believe that when I left home I was stupid enough to wear a T-shirt with my ID printed on it in big black letters.

But then I must admit I wasn’t in such a good state of mind when I left home – suicidal, in fact.

I’m much better now.

Now, I don’t care if I live or die.

Things seem to have taken a dangerous turn today, though. All morning, I have to avoid people who act like they’re about to grab me and take me to the police. They read my T-shirt, and then they get that look in their eye.

Pretty soon, the old feelings of being hunted from all sides start to come back. I’m walking with my arms wrapped around my chest, hunched over like a drug addict. The sun has gone away but I’m sweating. People are zipping up their parkas, glancing up at the sky mistrustfully, hurrying to shelter. But even under the threat of rain, some of them still slow down when they see me, and squint at the letters on my chest, trying to read them through the barrier of my arms.

By midday, I’m right back to the state I was in when I first went missing. I have pains in my guts, I feel dizzy, I can’t catch my breath, there are shapes coming at me from everywhere. The sky loses its hold on the rain, starts tossing it down in panic. I’m soaked in seconds, and even though getting soaked means nothing to me, I know I’ll get sick and helpless if I don’t get out of the weather soon.

Another total stranger calls my name through the deluge, and I have to run again. It’s obvious that my life on the streets is over.

So, giving up, I head for the Safehouse.

II

I’ve never been to the Safehouse before – well, never inside it anyway. I’ve walked past many times, and I know exactly where to find it. It’s on the side of town where all the broken businesses and closed railway stations are, the rusty barbed-wire side of town, where everything waits forever to be turned into something new. The Safehouse is the only building there whose windows have light behind them.

Of course I’ve wondered what goes on inside, I won’t deny that. But I’ve always passed it on the other side of the street, hurried myself on before I could dawdle, pulling myself away as if my own body were a dog on a lead.

Today, I don’t resist. Wet and emaciated and with my name writ large on my chest, I cross the road to the big grey building.

The Safehouse looks like a cross between a warehouse and school, built in the old-fashioned style with acres of stone façade and scores of identical windows, all glowing orange and black. In the geometric centre of the building is a fancy entrance with a motto on its portal. GIB MIR DEINE ARME, it says, in a dull rainbow of wrought iron.

Before I make the final decision, I hang around in front of the building for a while, in case the rain eases off. I walk the entire breadth of the façade, hoping to catch a glimpse of what lies behind, but the gaps between the Safehouse and the adjacent buildings are too narrow. I stretch my neck, trying to see inside one of the windows – well, it

feels

as if I’m stretching my neck, anyway. I know necks don’t really stretch and we’re the same height no matter what we do. But that doesn’t stop me contorting my chin like an idiot.

Eventually I work up the courage to knock at the door. There’s no doorbell or doorknocker, and in competition with the rain my knuckles sound feeble against the dense wood. From the inside, the

pok pok pok

of my flesh and bone will probably be mistaken for water down the drain. However, I can’t bring myself to knock again until I’m sure no one has heard me.

I shift my weight from foot to foot while I’m waiting, feeling warm sweat and rainwater suck at the toes inside my shoes. My T-shirt is so drenched that it’s hanging down almost to my knees, and I can read a telephone number that people are supposed to ring if they’ve seen me. I close my eyes and count to ten. Above my head, I hear the squeak of metal against wood.