The Female Detective (11 page)

Read The Female Detective Online

Authors: Andrew Forrester

Hearing this evidence, to which was added that of the

post-mortem

examination, I could readily comprehend why his face, and especially the skin about his mouth, assumed such appearances as they did each time I saw him; and I could also understand how thoroughly well-fitted by nature he was to agree with his doctor's direction to avoid excitement.

It was clear his was a nature where selfishness provokes a man, habitually callous and insensible, till his natural licentiousness moved and carried him beyond himself.

I say I have no doubt the medical evidence against Sir Nathaniel blunted the inquiryâa result not proceeding from any wilful hoodwinking of justice, but simply from the fact that human judgment must be made up of previous impressions. When men hear a dead man has been bad, they surely are not so desirous of talking over his coffin as they would be did they learn he had lived an honourable life.

The coroner's “Oh!” showed how much even an old legal official could be impressed by a witness deposing against the gentleman on trial. I know that coroner. He is not a very moral man, but he offered that hypocrisy of faultiness, open respect for virtue.

Miss Shedleigh's evidence, under my direction, had been given to the effect that Sir Nathaniel came about money matters; that when he fell he was about to seek Mr. Shedleigh, and that she had run forward entreating him not to carry out his intention.

And when the coroner and the jury learnt that Sir Nathaniel had for some years been supported by the Shedleighs, Miss Shedleigh was asked no more questions.

My tale of a “Tenant for Life” is done. It has been told to show how simple a thing may lead to most important consequences. Had I not taken that ride in Flemps's cab on a Sunday, I never could have learnt that Sir Nathaniel Shirley was the actual heir to the Shirley estates.

However, I am glad the baronet never possessed them.

When the little girl died (about eight months since) Mr. Shedleigh gave up the estates to the next heir after Sir Nathaniel. As it had never been proved that the child was not his, he by law was Tenant for Life; but he waved his right, not because he had learnt the secret of his sister's lifeâfor we kept it to ourselvesâbut because he felt that the only owner of the Shirley property should be one who claimed to be of the Shirley pedigree.

So it all came right at last, and no man was punished in order to procure justice.

1

. It is perhaps as well here to remark that the MS. of this work has been revised by an ordinary literary editor. It does not appear as actually written by the compiler. This supervision may be injurious to the

vraisemblance

of the work, but by its exercise some clearness of style has been attained.

I am about to relate here a tale which, as far as intricacy goes, has little to recommend it. But though it is a narrative of plain-sailing, I am inclined to give it a place here, because it once again illustrates pretty clearly how often it happens that popular and perhaps justly-grounded beliefs are in practice contradicted.

It is generally believed that a detective is not to be taken in. There is no greater error in relation to the police force. Once get the confidence of an individual of the home-bluesâand I know no man (or woman) so easily and persistently deceived. I grant you that it is not often we yield our confidence, but when we do the action is perfect.

Then again, it is generally supposed that boys in their crime are audacious rather than cunning. This is a great error. The cunning of a boy-criminal is generally brilliant.

Again, it is frequently stated that the young in crime suffer a good deal more from remorse than their brethren in rascality of a riper age. This is a belief which is not always borne out in practice.

I give this narrative because it combines, in a very simple form, the facts of a deceived detective, a cunning boy, and a young criminal quite destitute of remorse.

The deceived detective was myself.

The cunning boy was Georgy.

The young and utterly remorseful criminal, Georgy.

As I said before, Georgy is not the hero of a good plot; but perhaps his tale is worth hearing nevertheless, as showing what can be done by nineteen years and a cool hand.

This George Lejune was a dashing young gentleman indeed, and charming also. You could not be in the company of the boy for half an hour without taking a liking to him.

Bright-eyed, bright-lipped, laughing, clever (in his way), earnest, and upon the whole gentlemanly, he was rather a superior kind of lad.

Moreover, he was fairly modest; and during the few short months I knew him, I never found out that he had any pet weakness.

He dissipated in no form; he was too healthy looking for that. The only approach to weakness which I observed was now and then a tendency to Hansom cabs, which I used to hear roll up to the house next door after I had gone to bed.

I taxed him once with the cabs, but he had so good an answer for me that I dismissed those vehicles from my mind at once.

“You see,” said he, “I don't pay full fare, or anything like it. I wait till a cab is going my way, and then I tip cabby a tanner or a bob; and so I ride home for next door to nothing.”

What could be plainer than that statement? Only it wasn't true.

Then, again, when he told me that though he made but thirty shillings a week, he had it all to spend in pocket-money, as his mother had an annuity, that was an answer to his being well-dressed, and to his spending a little money. For upon thirty shillings a week pocket-money, you can have a decent coat to wear and carry clean gloves. Thirty shillings a week pocket-moneyâa plain statement enough.

Only it wasn't true.

I was living at the time (on business) at a small house at the east-end of London, and next door to the young man's mother. I took a liking to the boy from his turning out early of a morning, and singing like a lark as he looked at his flowers and fed his linnets. I defy you, if you have any heart, to mark a handsome boy, blithe, frank, and courteous, and not feel inclined to shake hands with him. I assure you this George shook you by the hand in the jolliest manner possible.

As I can make acquaintances very quickly, I was soon friendly with the mother; and finding her a very plain, simple-hearted woman, I was frequently in her house whenever my business would admit of my taking an hour to myself.

“I'm afraid Georgy spends too much money,” said she to me one night.

And so I, the detective, who by such a speech should have been put upon my guard at once, I saidâ

“No, Mrs. Lejune, the boy doesn't. He is young, and while he keeps his eyes bright and his spirits up, you need not be afraid.”

It is true he sometimes came home late, but I argued with myself that Bow was a long way from the theatres, and that he might be in the habit of going half-price to the pit.

But one evening, when I was at the house of his mother, who did not appear to be superabundantly well off, I confess the boy did startle me by appearing with what was evidently a diamond ring set open, and circling his little finger.

“Dear me, Georgy! says his mother,” “what a fine ring you've got there. You've been wasting your money again. What is the use of your working extra time and making extra money if you spend it so wastefully.”

“Indeed!” I said, “he must have given quite a handsome amount for that ringâit is a diamond.”

“Dear me, Georgy!” says his mother, “why whatever have you been buying diamonds for?”

“It's only one, mother; and besides, I didn't steal it, it was given to me.”

“Dear

me

, Georgy, who could have given you a diamond?”

“Why, mother,” says he, laughing gaily all the time, “don't you remember I told you Lieutenant Dun, Mr. Clive Dun's brother, had come home on furlough; and don't you remember that I went to Dun's with Dun's friend, Will, on Friday, to a night at cardsâwell, Lieutenant Dun gave me the ring.”

N.B.

This conversation took place on the Monday.

“But, my dear Georgy, you've only seen the gentleman twice!”

“Well, mother, I can't help that; but the lieutenant said I was a very jolly fellow, and he gave me the ring.”

As I said before, this was on the Monday.

He was only nineteen.

On the Friday following, as I learnt afterwards, he said to his mother at breakfastâ

“Mam dear, you must give me a kiss after breakfast, because you wont see me till to-morrow.”

“My dear Georgy,” I am quite sure she replied, “where are you going?”

“Oh, the Duns have asked me to their uncle's to dinner, and it's ten miles out of town, and they will give me a bed.”

So he kissed his mother. “My dear,” said she, “as light hearted as ever he kissed me, and he went out and talked to the linnets, and plucked two or three flowers and put them in his coat, and he went away down that front garden, which there it is, singing as happy as any one of those dear linnets.”

And yet he had taken the long farewell of his mother.

He has never seen her again.

I think in all probability he never will see her againâand this probability he must have been aware of as he went singing down the gardenâsinging, not because he had a light heart, but because he was cunning enough not to show the least suspicion, and because I suppose he could not feel remorse.

When Friday night came he was not missed because he was not expected home.

When Saturday morning came he was not missed because it was supposed that he would go straight to office from the hospitable country house.

Therefore it was only when the mother had waited up all Saturday night and Sunday morning had arrived, that any distinct notion would be come at that perhaps something had happened.

But now it was Sunday, and upon that day the innocent mother could give no warning of the actual state of things, no warning, that is,

at the office of the boy's employers

. So another day passed, and it was only on Monday morning that the firm got their shock.

For “Georgy,” the gay, singing lad of nineteen, had managed matters so well both at home and abroad, that no suspicion of the truth could be taken at the office till the Monday.

This was his little arrangement.

Arriving on the Friday morning at his office, (after giving the very last good-bye to his mother) he asked permission to leave at noon, as he wanted to go into the country, and he further requested leave till the Saturday (the next day) at noon.

The firm, or rather its representative, gave way, being a sufficiently easy-going man.

“Oh, by the way,” says Georgy, “as I'm going in the country, sir, I may want a little moneyâif you will give me a cheque for the month I shall be glad.”

“Oh, certainly,” says the principal, and I have no doubt the request for that poor little cheque helped to put off the uneasiness that principal was to feel sooner or later.

The whole business was so plausibleâthe visit to the country on the Friday, the permission for a couple of hours' grace the next morning, and finally, the request for the month's small salary, were all so rational and all so agreeing in themselves, that there was no room for suspicionânot even for that of a detective.

Now mark how well the plan was laid.

He had got clear till the Saturday at noon. Then he was not expected till noon on Saturday. But the office, in common with most others, was closed on a Saturday at two; therefore, when the closing hour for the week came, Georgy would but be two hours behindhand, a space of time which might be accounted for by supposing he had missed a train.

This was the literal construction put upon his absence, and therefore the firm went home with a serene breast, and passed Sunday without any doubt or uneasiness in reference to Georgy.

Now it will be seen that had this singing innocent of nineteen absconded on any other day than Friday, suspicion would have been aroused within twenty-four hours, or at their expiration; whereas by choosing Friday he got nearly

three

days' clear start before he was missed at his office, or any warning of his departure from his innocent mother could reach the city establishment.

In my detective experience I have come across much fine delicate management, but I never encountered an instance of more decided and well plotted rascality than that of George Lejune.

Of course within an hour of suspicion being raised, it came out that there were defalcations. Before the day was out a deficit of nearly £300 was discovered; the existence of which deficit was clearly attributable to the young man.

He had deceived every soul about himâme amongst the rest.

At any moment during the previous two months he had been liable to be taken into custody; at any moment he might have found himself ruined for life, and yet, to my certain knowledge, he was apparently happy, and evidently healthy, bright-eyed, and brightlipped to the very last.

The young man could not have had any comprehension of morality, and, at the same time his bodily health must have been wonderful.

Of course the very pretty facts spread with great rapidity. The city detectives were especially busy in circulating the news.

The felonious performance had been effected in the most delightfully simple way.

The firm was careless in money matters â rarely checking its banker's book. This the very young gentleman discovered almost directly he had taken possession of his office-stool, and, it is possible, at once he made up a felonious mind. I should add that he was not altogether more than three months in the employment of the firm he robbed.

The whole of the large embezzlements were effected within two months of his absquatulation. His plan was marvellously simple, but ingenious.

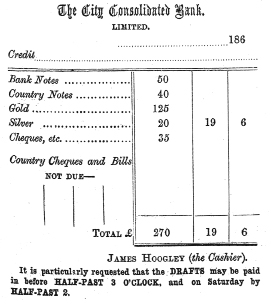

My readers may know that it is the plan in the city, when paying into the bank, to send a paper with the amount to be put to the account of the customer, which amount is the total of the bills, cheques, notes, gold, and silver paid inâsuch items being put down separately, and the whole added together.

This draft, of money to be paid in, was made out by the cashier of the office honoured by the young Lejune, and then Georgy became the porter to the bank. His operation was very simpleâsuppose the draft stood thus:â

The first manoeuvre was to forge the cashier's name to a new draft, made an exact counterpart of the last, except that the gold item instead of being £125 was £25, so that the total stood £170 instead of £270.

Now mark the brilliancy of the felony.

It was he who had the carrying to and fro of the bankbook.

At the bank they would discover no fraud because the book agreed with the draft, while as soon as anything like suspicion were raised in the office he would be the first clerk applied to, to ascertain what had happened.

Now suppose in the given case the cashier had discovered that only £170 19

s

. 6

d

. instead of £270 19

s

. 6

d

., had been paid in, and suppose that cheerful young man, Lejune, had been called to explain the matter, what would his reply have been?

“Oh, I see; it's only a mistake in a figureâa 1 for a 2;” and this argument would have stood very well, because all the rest of the figures would tally in the bank-book and office cash-book.

“Dear me!” the cashier would have said; “go down to the bank and have it altered.”

“Yes, sir.”

He would then have gone, and never come back again.

It is true he would have had a poor start, but that was a risk he ran.

When I came to examine the case I found it exhibit such thought and study that it was some time before I could persuade myself that he had not been helped by an old and experienced hand.