The Fence: A Police Cover-Up Along Boston's Racial Divide (31 page)

Read The Fence: A Police Cover-Up Along Boston's Racial Divide Online

Authors: Dick Lehr

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Political Science, #Social Science, #Law Enforcement, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Ethnic Studies, #African Americans, #Police Misconduct, #African American Studies, #Police Brutality, #Boston (Mass.), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #African American Police

It all meant Peabody had less to work with, and by the time of his face-off with Williams on Friday, December 1, he’d lost the zip and confidence he’d started with. Sunday evening from his home, he typed an e-mail to Ralph Martin. The session with Williams, he told his boss, was “not what I hoped for.”

Peabody continued, “He stood his ground when confronted with damaging statements he supposedly made to others who have testified. He flatly denied yelling, ‘Stop, he’s a cop!’ when Cox was getting hit and denied telling Craig Jones later that night, ‘I think my partner hit your partner.’”

Williams, wrote Peabody, “said he saw and did nothing other than chase the murder suspects.”

If it all sounded defeatist, Peabody wasn’t ready to fold yet. Williams, he said, was the key. “I think he saw it and has convinced himself that this is the story he is going to give, or he really didn’t see what happened, believes that his partner was probably involved and has decided to protect him as best as he can.” Peabody said he had an idea. “It is time to confront Williams. Lay our cards and theories on the table and see what he says. There are sufficient contradictions now on the record to smoke him out if he’s hiding it.” Peabody wanted to arrange a meeting with Williams and his attorney.

He wanted to let it all hang out. It would be a Hail Mary.

Mike jerked upright and leaned over the back of the couch. Groggy with sleep, he took a split second to get his bearings. Then he carefully pulled back the curtain to peek outside. He was convinced he’d heard something. But Supple Road was quiet. He looked up and down his street. He saw nothing, at least not what he was looking for. His unmarked police cruiser sat in front of his house, untouched.

Mike had taken to sleeping on the living room couch after finding the first tire slashed one morning when he left the house for work. “I was trying to catch them.” But he hadn’t, and over the next few weeks, the other three tires were cut up. His car was clearly targeted; it was the only one on the street that was hit. Mike was certain cops were the culprits, cops who’d adopted yet another technique to communicate what they thought of him, “that I was becoming some type, you know, of rat.” In the police world, tire slashing was known to be one way cops expressed displeasure with one another.

The harassment started as officers received subpoenas in late summer to appear before Peabody’s investigative grand jury. Mike’s return to work was not going well. “I’d just walk into a room and, you know, people look at you like you’re dirt.” Mike listened to some commanders reassure him his beating was unacceptable, but the talk was empty, particularly when he could just look around and see actual suspects still on the job. No one had yet been disciplined in any way, despite all the lies the investigation had already established. Some were even promoted. Sergeant Dan Dovidio, for one, rose to the rank of sergeant detective. Not only that, he was transferred to Internal Affairs. It couldn’t have gotten any more bizarre—the supervisor who’d retreated to the police station when nearly every cop on duty was racing to the shooting at Walaikum’s, the supervisor who’d told Williams and Burgio at Woodruff Way to lie about riding in the same cruiser, was now seen by the commissioner as having the right stuff to uphold the department’s integrity and standards of conduct.

It was all a bit hard for Mike and Kimberly to take. “Life for me became more and more difficult,” he said, “and I just didn’t understand, you know, why? What did I do to create all this hostility?” Mike had several times changed their telephone number and had it unlisted, but that didn’t matter. The crank calls continued, albeit with periodic breaks. Then one night a crew of Boston firefighters and fire trucks arrived in the middle of the night, apparently summoned by a false report that the Cox house was on fire.

Now there were the tires. When Mike lay back down on the couch, a video camera, pointed out of the living room window, continued making its slow, whirring sound. The camera was aimed straight at Mike’s cruiser. The car’s shadowy image was displayed on a monitor attached by cables to the camera.

Farrahar’s Anti-Corruption investigators had installed the camera. It was a primitive setup, requiring Mike to actually “do a lot of rewinding and setting up of this equipment, turning it on and off.” Kimberly was unimpressed; the setup, she said, was a “joke. It’s like it was something from 1950s. The picture was so unclear, it was just basically fuzz.” It seemed so ineffective. “See a picture? I mean, looking at it, I couldn’t make out much of anything; maybe shadows.” Within a couple of weeks, she and Mike had had enough of the Boston Police Department’s putative high-tech capabilities. The camera was more a nuisance than anything else, and they insisted it be removed. Mike would keep trying to capture the slashers on his own.

Kimberly was put off by the whole thing. To her, the clunky surveillance equipment was a token, even patronizing response. “I didn’t think that was a serious attempt for them to find out who was doing this.” In fact, it became a symbol for how the couple now viewed the overall investigation—halfhearted, bungled, and wanting.

By early fall, Mike had seen enough. He’d always believed in the system, but he now reached the conclusion the system had fallen short. “I was failed by the police department.” Just as he was on his own when it came to the tire slashers, Mike decided he was on his own in the search for justice. “I had to do something,” he said, “regardless of what the DA’s office or the police department was going to do.” The continual harassment, rather than a deterrent, had become a prod. “I decided, along with my family, that I needed to find out, you know, who was involved, who did this.” Mike realized he was going to have to take matters into his own hands.

He hired Steve Roach and began meeting regularly with the attorney. Then, in late fall, as Bob Peabody was unsuccessfully pushing Dave Williams to come clean, and six days after Bill Bratton’s appearance at Harvard Law School, Mike sued. He sued his fellow cops, his police department, and his city. He said his civil rights were violated when Boston police officers repeatedly beat and kicked him until he blacked out. He charged that David C. Williams and Ian A. Daley witnessed the attack, did nothing to stop it, and then left him injured and unattended on the street. He took on the police culture of silence and said the two officers joined others in a cover-up and failed to report the assailants. And Mike took on the Boston Police Department. The department, he said, “fails to investigate allegations of misconduct by police officers, fails to properly supervise police officers and fails to properly train police officers and their supervisors after having prior knowledge of multiple incidents of misconduct, especially against young black male suspects, other powerless citizens and plainclothes officers.”

Mike was in metamorphosis—moving from cooperating victim in others’ investigations to aggressor in the quest to hold his assailants accountable. He’d been a punching bag that night at the fence, and he’d felt like one ever since. It was now about “my self-esteem” and “my family.” He could no longer be a bystander.

“It was humiliating what happened to me,” he said. “There’s no reason to treat anyone like that. And then to just leave them. And if they do it to me—another police officer—would they do it to another person if they got away with it?

“What’s to stop them? Who’s to stop them?”

On December 31, an estimated one million revelers turned out for Boston’s First Night activities. It was the twentieth year the city hosted a long day’s celebration into the night, featuring towering ice sculptures, a parade, puppet shows, music concerts, and, at midnight, a fireworks display over Boston Harbor. For the occasion, more than two hundred Boston police officers and ninety-one police cadets were deployed to keep the city’s record of a festive and peaceful New Year’s Eve intact. “We’re going to keep this a safe and enjoyable way for people to celebrate,” Mayor Menino promised beforehand.

Mike Cox was not feeling particularly celebratory or safe. He’d filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against his police colleagues and his department. He knew he was stepping way out of line. “I have accused them of things which I don’t necessarily know anybody else in the police department has ever done before.” The claims could cost them their jobs and monetary damages, and “it could send them to jail.”

Taking legal action may have brought some satisfaction, but Mike now wrestled with the fear factor. For Mike, it went like this: He’d become a troublemaker, and the quickest way for those troubles to end was “by me not being on this earth or being killed.” That was the way Mike Cox’s year ended—believing his life was at risk. It wasn’t the unfounded fear of an outsider. Mike was one of them. He’d been a cop for six years and knew the score. He understood completely that his lawsuit meant that he was locked in combat against the police culture, and, by taking it on, he had become the enemy.

THE

PHOTOGRAPHS

Mike Cox’s boyhood home in Roxbury at 60 Winthrop Street.

Mike Cox in his 1984 high school yearbook. His classmates voted him “class flirt.”

Kenny Conley in elementary school in South Boston.

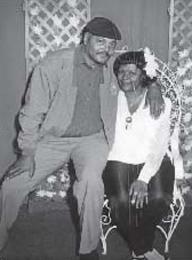

Smut Brown’s mother, Mattie, and father, Robert Brown Jr.