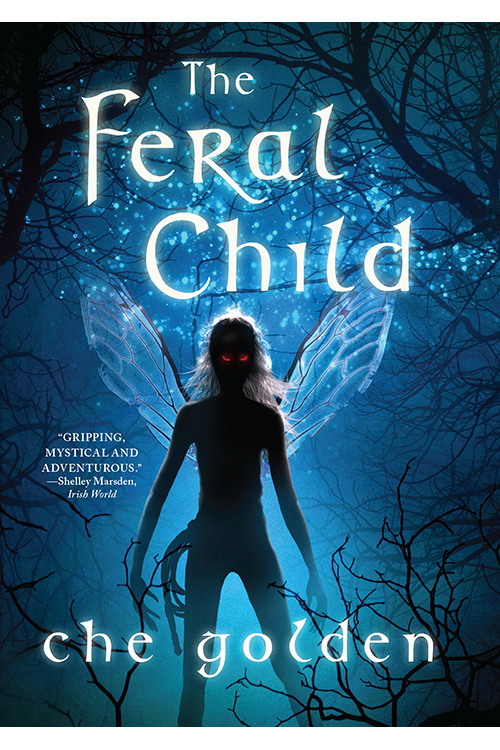

The Feral Child

New York • London

New York • London

© 2012 by Che Golden

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to

[email protected]

.

e-ISBN 978-1-62365-121-3

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, institutions, places, and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons—living or dead—events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For Paul, who has a hard time believing in faeries but always believed in me.

Contents

Maddy scowled and scuffed her sneakers

along the ground. Each time she saw a loose stone, she aimed a vicious kick at it, pretending it was Danny’s head bouncing along the street.

God, she was sick of living in Ireland, sick of Blarney, and sick of her idiot cousins. She used to cry when she had to get back on the plane to return to London after visits to her grandparents. She snorted. What a baby she had been. Now London and all her friends might as well be on the other side of the world. She was stuck in tiny Blarney, in freezing County Cork, dealing with jerks like Danny, one of the nastiest people you could meet this side of a restraining order.

What really annoyed her was that Danny was family, her cousin. But Danny and the rest of her cousins

had been making it very clear for the last year that they didn’t have time for her. She gritted her teeth and felt her cheeks warm as she remembered Danny standing in front of her that afternoon, smirking at her. He was hitting his little sister Roisin, and Maddy had made the mistake of coming to her defense.

“This has got nothing to do with you,” he sneered. “You’re only here because your parents are dead and no one else wants you. Why don’t you piss off back to England?”

“Trust me, mate, I would if I could,” she said, just before she punched him in the face. And what had Roisin said or done when Danny hit Maddy back and the fight started? Nothing! Wouldn’t even look her in the eye.

Of course, all the adults thought the fight was her fault, seeing as she had thrown the first punch. No one seemed to care about provocation or extenuating circumstances. That’s why she was wandering the road, walking a dog that normally walked itself, while her cousins got ready to go home. Granny had just handed her the dog’s leash and pointed at the door. “Don’t you go into the castle now,” she had said, before she closed the door on Maddy. “Walk him once around the square and then home.”

It amazed her, it really did, that her grandparents or her hideous aunts still thought she gave a toss about their rules or anything they had to say. It was

boring

walking George, her grandfather’s black and white

terrier. He didn’t seem too impressed either. He hopped and bumped along behind her as she dragged him by his leash.

She stopped to look up at the ruined castle that loomed over the tiny village of Blarney where her grandparents lived. George crashed into the back of her leg and huffed. She ignored him as she gazed up at the keep, its broken battlements letting long golden shafts of autumn sun break through. It looked like something from a faerie tale. Her grandfather was always trying to terrify her with tales of ghouls, ghosts, and wicked faeries that lived in the grounds, who stole children and took them back to Faerie Land, never to be seen again. She snorted. As if.

“What do you say, boy?” she said to the dog. “You don’t want to go on a boring walk, do you? I bet

you

want to do something much more exciting.”

George barked and wagged his tail.

It was far too easy to crawl through a hole in the fence that separated the castle grounds from the parking lot, and an overgrown bush hid her from interfering grown-ups as she pulled George in after her.

She could see her grandfather talking to one of the groundskeepers, Seamus Hegarty. Granda was the gatekeeper to the grounds, but he didn’t have much to do at this time of the evening—no one bought entry tickets this late. The path to the castle was lined with huge oak trees, and Maddy and George darted from one to another to keep well out of her grandfather’s sight as he

idled by the ticket booth. The path curved into a bridge that crossed a sluggish river, evil-eyed pike cruising in its depths. Once they scooted over the bridge, they were out of sight, and they ran toward the medieval keep, in the opposite direction of the tourists who chattered and stopped only to take last-minute photos.

Its gray walls leached any warmth from the weak autumn sun, and its shadow lay heavy and clammy. Water seeped constantly down its rough-hewn stones, and ferns flourished at its base. Ivy clung to the lower reaches, leaves lapping at the rock’s sweat. The old keep squatted and squinted with arrow-slit eyes at the fields and woods before it. A cave nestled deep into its roots yawned as Maddy jogged past, the damp air that fanned from it as cold as corpse breath.

But it wasn’t the castle Maddy was interested in, with its retinue of ghosts. Instead, she headed for a little tunnel dug into the hill at the foot of the castle that led to some very strange landscaped gardens. Grown-ups had to bend almost double to walk through, but Maddy comfortably jogged along, the hair on her head only brushing the wet stone.

Years ago, someone had decided to give the tourists a taste of old Ireland with a faerie kingdom. The tunnel opened up into a world of moss-covered evergreen trees and cool ferns that nodded next to the gurgling river. It had wooden signposts with Celtic-style lettering that pointed out things like “The Witch’s Cave,” “The Wishing Steps,” and “The Faerie Mound.” It was

guarded by crows that screamed in the branches and glared down at Maddy with their cruel black eyes.

Her cousins thought the place was lame and that she was a baby for liking it so much.

They must think I’m thick

, thought Maddy,

if they think I don’t know the faerie mound is a just a pile of earth created by a backhoe

. Just as she knew the witch’s cave had been built by the bricklayer who lived next door to her grandparents.

She let George off the leash, and they left the path for the gloom of the woods. George ran after her with his tail wagging. The birds were roosting in the trees, and she could hear the faint sound of a bell ringing in the grounds, a warning that the gates would soon be locked. But she ignored it—she still had a few minutes before it was completely dark, and she could always let herself back out through the hole in the fence.

She sat with her back to a gnarled pine tree and brooded. It wasn’t a good thing to do; she knew that. Her teacher was always telling her to rise above things, to think good thoughts when she was having a bad day, but clearly the woman didn’t have a clue, if she thought that worked. The hurt and the anger soured in Maddy’s stomach. Everything Danny had said today, everything her cousins said any day, kaleidoscoped through her mind. Every time she tried to join in with a game or a discussion, it was always the same. They shrugged her off with, “Who cares what you think?” “Who cares what you want?”

She missed London. She missed the lights and the traffic and the people. London was alive. It had energy that fizzed up through the concrete to the soles of her feet. Blarney didn’t even have a Pizza Hut. She couldn’t tell anyone that though. They’d think she was being a stuck-up Londoner, trying to act like she was better than they were.

“Well, I am,” she said aloud in the gathering gloom. “London is better than this dump any day of the week.” She stood up and yelled at the top of her lungs, “I’M FROM THE INDEPENDENT REPUBLIC OF LONDON!” Her shouts sent crows flurrying into the sky, cawing with annoyance. She laughed, her voice flat with the dull edge of her anger.

George looked at her with what she thought was an accusatory stare in his narrow brown eyes.

“I know I look like a psycho,” she said, “but everyone keeps telling me I’ll feel better if I let it all out, so if you don’t like it, ask Santa to bring me a punching bag.”

The dog’s face and sides twitched like he was trying to spit a reply out, and then he twisted around and started to chase a flea through his fur with yellowed fangs.

She sighed. The sun was sinking. It was just a sliver of red on the horizon, a sore spot in a turquoise sky. Beneath the trees it was already night.

She was about to walk home when a rabbit came hopping out of the undergrowth. It froze when it spotted George, who got to his feet and stretched his neck in

anticipation. Too late, the rabbit tried to make a run for it, and before she could grab him, George tore after the animal, his little legs blurring as he gave chase.

“George, NO!”

He was gone before she had run more than a few steps.

“Oh, marvelous,” yelled Maddy. “Just bloody marvelous!”

She was really in for it now—her grandparents were going to kill her for losing that idiotic dog. She sighed. It was getting too dark to search for him. She was better off going back to her grandparents’ house and hoping the terrier would come home when he was hungry. A bad end to a really bad day.

“Why are you so angry?” said a voice close to her ear.

She jumped out of her skin with fright and looked around to see a little red-haired boy standing beside her. She hadn’t heard him creep up on her, and she glared at him.

“Where the bloody hell did you come from?” she asked.

The boy widened glass-green eyes at her and twisted his lips. “Do your mommy and daddy know you swear like that? Mine would never allow me.”

She stared at him for a second while her heart twisted in her chest. Was it possible that there was someone in this village who did not know why Maddy’s parents couldn’t care less about her language? Her throat hardened with tears. She couldn’t trust herself

to speak so she clambered to her feet and walked away. But the boy trotted to catch up to her, and he angled his head to gaze up into Maddy’s lowered face.

“Why are you crying?”

“It’s none of your business.”

“You are very rude. I’m only trying to be nice to you.”

“Well, I’m not in the mood, so bugger off and leave me alone,” snapped Maddy.

She carried on walking and calling for the dog, straining her ears for any sound of George. She dug her nails into her palms and prayed the dog would come back in the next five minutes. But there was no sign of him, and her new pal wasn’t taking the hint either. She could hear boy’s feet scuffing the dead leaves as he walked after her, and she sighed loudly when he started talking again.

“My name is John, by the way. You can come and play with me, if you like. I’ve got a toy gun and a bow and arrow—we could take turns playing cowboys and Indians.”

“No, thanks,” said Maddy.

“We don’t have far to go. I live in here.”

“Don’t tell lies, you freak. No one lives in here.”

“I’m not, and I do. Where are your parents?”

“None of your bus—”

“Do your parents live with you? Are they waiting for you at home?” he interrupted.

She gritted her teeth and zipped her jacket against the autumn chill.

Bugger off, bugger off, bugger off, you JERK!

she snarled inside her head.

Perhaps she should have said it out loud because now he was rummaging through his pockets and pulling out a white paper bag. “Would you like a candy?”

“Are you slow or something?” said Maddy. “I mean, do I look like I’m friendly? Do I look like I’m in the market for a new pal?”

The boy cocked his head on one side. “You feel very lonely.”

That was it.

Feel

was a trigger word for Maddy. Anger bubbled up like molten lava in her throat, and she swung around and pushed her face into his, her hands balled into fists. “You know how I

feel

, do you? What a relief—I really need someone to tell me how I’m feeling. Here, pal, how does this

feel

?” She hammered her fists against his chest, a half-punch, half-shove that normally sent most kids staggering backward, while the anger popped and fizzed in her mouth.

But John didn’t even grunt as her hands thumped out a dull note on his ribcage. He only grinned at her, flashing very sharp white teeth. “How delicious—anger too.”

Something wasn’t right here, and if she hadn’t been so busy being angry, she might have noticed the signs sooner. Like the fact that no one normal played cowboys and Indians at her age or called their parents “Mommy” and “Daddy.” She watched him licking his lips, his unblinking eyes locked on hers. “That’s it, you nut job, I’m out of here,” she said.

As she turned to go, she felt his hand clamp on to her arm. She could feel his nails digging through her jacket,

and she was shocked at how strong he was for such a skinny kid. The white paper bag fell from his grasp, and as the pieces of candy tumbled on to the grass, she thought she saw the green blades turn black.

“There’s something else as well,” he said, sniffing the air like a dog. “Something older and riper under all that anger. Ah, yes.” He fixed his eyes on hers again. “Despair. A deep, deep pit of despair.”

She tried to jerk her arm away, but he didn’t even flinch. “Let go of me,” she hissed.

“Why would I do that, when you are such a rare find?” He smiled and tipped his head to one side again as he looked at her. “Such rage and hatred in a child. Life just isn’t worth living, is it?”

Maddy went cold. Kids didn’t talk like that.

No one

talked like that. She tried to pull away, but he had a tight hold on both her upper arms now, and he began drawing her back toward the shadows. Her mouth went dry with fear, and she twisted around, pulling out of one of his hands, and she tried to swing a punch, but he dropped her other arm and caught her fist in the palm of his hand. Then he began to crush her fingers and bear down on her upraised arm with all his weight. She screamed as the pain rocketed toward her elbow and her knees buckled underneath her. He bent down until his face was close to hers. His glass-green eyes seemed to float toward her, hanging in front of her sweat-streaked face like glowing balls.

“If you stop struggling, it will be much easier,” he said. He wasn’t even out of breath.

Maddy froze. “What will be easier?”

“Coming with me, of course.”

She looked up at him, and fear turned her stomach to ice as she realized what he meant.

It’s happening

, she thought.

It’s actually happening. I’m being abducted, and it’s not some creepy old man doing it. It’s a really creepy kid.

She began to cry as he forced her down on to the earth until her free hand was splayed among the leaves as she fought to stay upright, her other arm burning in its socket. Her tears mingled with her sweat and filled her mouth with salt. She thought of the streetlights, the noisy pub, the people out walking their dogs, and her grandparents sitting in their living room, wondering where she was. The whole of bright, breathing Blarney village was only a hundred yards away on the other side of the castle fence. She wished she hadn’t come in here, wished she was sitting down to dinner with her grandparents right now, with George eating noisily from his bowl in the corner. She could not stop looking into the strange boy’s eyes. Her body went numb. She could hear the crows screaming, but when she opened her own mouth, only a hoarse croak escaped.