The Final Crumpet

Authors: Ron Benrey,Janet Benrey

Tags: #Mystery, #tea, #Tunbridge Wells, #cozy mystery, #Suspense, #English mystery

| The Final Crumpet | |

| A Royal Tunbridge Wells Mystery [2] | |

| Ron Benrey Janet Benrey | |

| Barbour Publishing (2005) | |

| Rating: | *** |

| Tags: | Mystery, tea, Tunbridge Wells, cozy mystery, Suspense, English mystery |

Etienne Makepeace, England's celebrated "Tea Sage," vanished without a trace in 1966, leaving the whole of Great Britain wondering what became of the famed radio personality. Forty years later his hastily buried remains are discovered beneath two sickly Assam tea bushes in the Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum's tea garden--"along with the pistol that killed him. Nigel Owens, curator, and Flick Adams, tea chemist, are thus embroiled in the second mystery to threaten the integrity of the museum. Are they in over their heads this time?

Contents

The Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum

Book Two: The Royal Tunbridge Wells Mysteries

THE FINAL CRUMPET

By Ron & Janet Benrey

A Note From the Authors

This book is a novel, but Royal Tunbridge Wells is quite real. We have tried to faithfully describe many of the town’s well-known locales. As it happens, Janet grew up on the very patch of land where we located the “Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum.” The museum is fictional—although it has become a living, breathing institution to us.

In fact, it even has its own website. Please visit:

www.teamuseum.org

Ron and Janet Benrey

The Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum

One

T

he roaring clatter made by the little “mini excavator” astonished Nigel Owen. The compact tractor equipped with a crablike digging arm sounded as loud as a full-size bulldozer inside the enclosed confines of the tea garden. Nigel wanted to clamp his hands over his ears, but his left arm was stalwartly enfolding Flick Adams’s shoulders, and she had tightly gripped his right hand between both of hers.

“I can’t bear to watch this,” she shouted, as the small earthmover began to roll along the garden’s serpentine redbrick path. “I’m having second thoughts about tearing out our Assam tea plants just because they didn’t grow to full height.”

Nigel didn’t feel much sympathy for the two scraggly evergreen shrubs planted in the Indian Tea area of the garden, but Flick clearly did. He bent close to her ear.

“Those Assam bushes have led long and happy lives. If they could talk, they would applaud your decision to uproot them.”

“Then why do I feel like a vandal?”

“Because you have focused too closely on the fate of two individual plants. Think of the big picture. We have twenty-two tea bushes in this garden. Replacing ten percent of them represents prudent husbandry of the museum’s precious resources.”

“Okay, so maybe I’m not a vandal. But what do you call a person who destroys history? Our predecessors planted those Assam bushes decades ago.”

“Yes, they did—for the specific purpose of educating visitors to the Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum. However, these particular tea plants routinely confuse our current day visitors. As you have repeatedly explained to me, there are three major varieties of tea plants grown throughout the world: the China, the Assam, and the Indo-China. The Assam is supposed to be the tallest of the three; consequently the founders planted only two of them. But our Assam tea plants look more like bonsai miniatures. You sensibly chose to replant this corner of the tea garden with new Assam seedlings.” He gave her shoulders a reassuring squeeze. “As the newly appointed managing director of the museum, I hereby certify that you are doing a wise and proper thing.”

“You may be right, but you may also be wrong. While it’s perfectly true that a healthy Assam plant can soar to more than sixty feet, tea growers routinely prune them back to a height of four or five feet for convenient picking of tea leaves. Our stunted bushes are really quite realistic.”

Nigel squeezed Flick’s shoulders again and fought the urge to laugh. How could Felicity Adams, PhD, who knew

everything

about tea, think of any tea plant growing in Kent, England—tall, short, or in-between-as being “realistic”?

The very existence of this tea garden was a tribute to the extraordinary lack of realism exercised by the museum’s founders some forty-one years ago. They began by surrounding a fifth of an acre of land on the eastern corner of the museum building with a twelve-foot-high brick wall to block out chill breezes. Then they ordered a grid of iron pipes buried three feet below the surface. Two powerful pumps circulated heated water through the subterranean plumbing by day and by night, to keep the Kentish soil, and the sheltered garden itself, balmy enough to raise tropical tea plants.

Nigel gazed up at the ugly gray sky and decided that this very day provided a fine illustration of the founder’s accomplishments. Outside the garden, one had to endure an icy Friday morning in mid-January, but inside the wall, one could relish springlike surroundings. He and Flick had both left their cumbersome winter trench coats upstairs, in their respective offices.

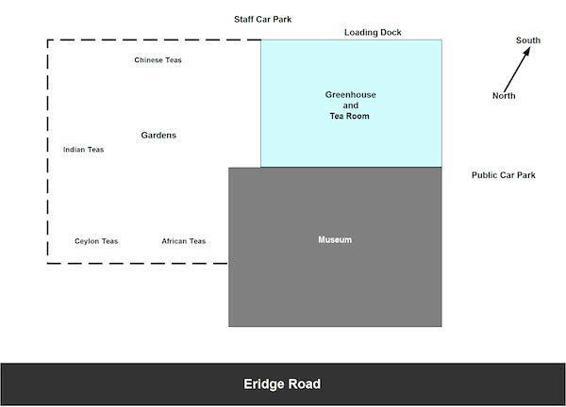

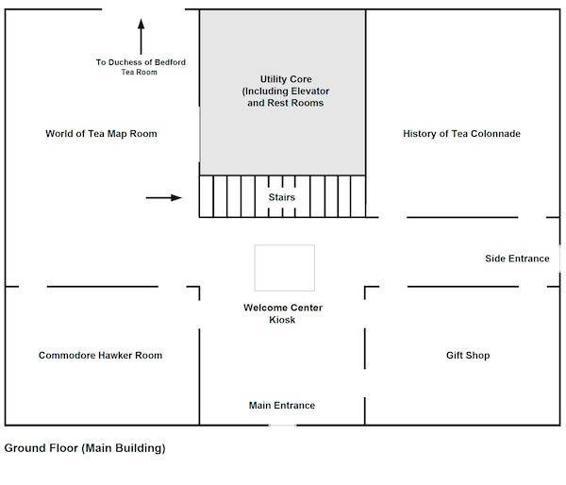

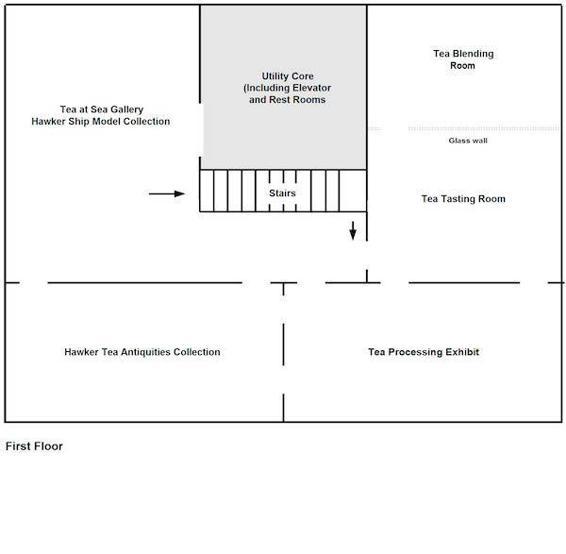

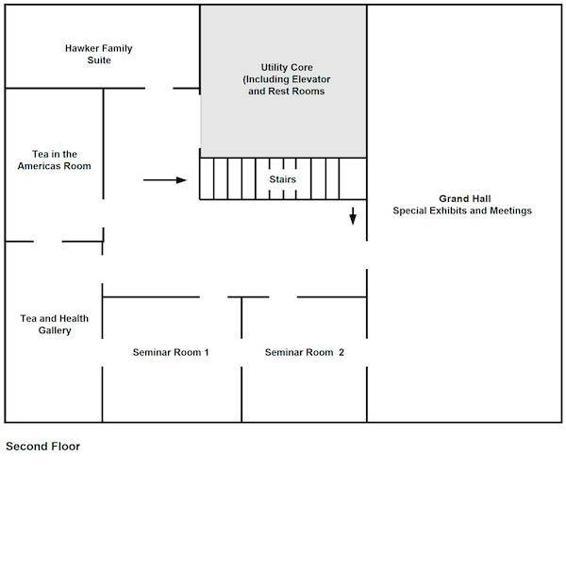

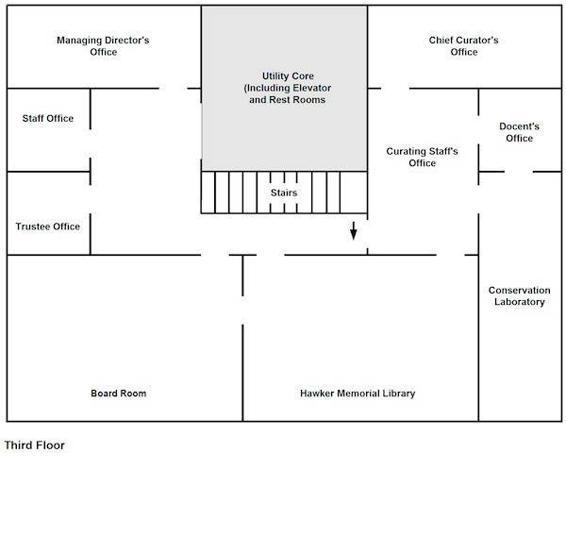

Of course, if one thought about it, there was a touch of the implausible about the whole of the Royal Tunbridge Wells Tea Museum. There it stood on Eridge Road: an imposing, four-story, Georgian-style building dedicated to the many different aspects of tea. The history of tea, the geography of tea, the economics of tea, the cultivation of tea, the processing of tea, the blending of tea, the tasting of tea, the serving of tea, the food that accompanies tea—if a topic had something to do with tea, one could probably find a relevant exhibit in the museum’s galleries, library, meeting rooms, garden, or laboratories. How could sensible Brits give over such a significant institution to the veneration of a mere beverage?

Don’t forget the most improbable thing of all.

The transformation of his own life. He had come to Tunbridge Wells ten months earlier as the museum’s acting director, a one-year-long temporary position intended to tide him over between “real” jobs. He had had every intention of returning to London, no desire at all to make a sea change in his career. And not the least notion of falling in love with the chief curator.