The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales (4 page)

Read The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales Online

Authors: Arthur Ransome

Midnight tied up his head with a handkerchief, and lay down under the bench, groaning and groaning, unable to put his head to the ground, or even to lay it in the crook of his arm, it was so bruised by the beating given it by the little old man.

In the evening the brothers rode back, and found Midnight groaning under the bench, with his head bound up in a handkerchief.

Evening looked at him and said nothing. Perhaps he was thinking of his own bruised head, which was still tied up in a dishcloth.

“What's the matter with you?” says Sunrise.

“There never was such another stove as this,” says Midnight. “I'd no sooner lit it than it seemed as if the whole hut were on fire. My head nearly burst. It's aching now; and as for your dinner, why, I've not been able to put a hand to anything all day.”

Evening chuckled to himself, but Sunrise only said, “That's bad, brother; but you shall go hunting to-morrow, and I'll stay at home, and see what I can do with the stove.”

And so on the third day the two elder brothers went huntingâMidnight on his black horse, and Evening on his horse of dusky brown. Sunrise stood in the doorway of the hut, and saw them disappear under the green trees. The sun shone on his golden curls, and his blue eyes were like the sky itself. There never was such another bogatir as he.

He went into the hut and lit the stove. Then he went out into the yard, chose the best sheep he could find, killed it, skinned it, cleaned it, cut it up, and set it on the stove. He made everything ready, and then lay down on the bench.

Before he had lain there very long he heard a stumping, a thumping, a knocking, a rattling, a grumbling, a rumbling. Sunrise leaped up from the bench and looked out through the window of the hut. There in the yard was the little old man, one yard high, with a beard seven yards long. He was carrying a whole haystack on his head and a great tub of water in his arms. He came into the middle of the yard, and set down his tub to water all the beasts. He set down the haystack and scattered the hay about. All the cattle and the sheep came together to eat and to drink, and the little man stood and counted them. He counted the oxen, he counted the goats, and then he counted the sheep. He counted them once, and his eyes began to flash. He counted them twice, and he began to grind his teeth. He counted them a third time, made sure that one was missing, and then he flew into a violent rage, rushed across the yard and into the hut, and gave Sunrise a terrific blow on the head.

Sunrise shook his head as if a fly had settled on it. Then he jumped suddenly and caught the end of the long beard of the little old man, and set to pulling him this way and that, round and round the hut, as if his beard was a rope. Phew! how the little man roared.

Sunrise laughed, and tugged him this way and that, and mocked him, crying out, “If you do not know the ford, it is better not to go into the water,” meaning that the little fellow had begun to beat him without finding out who was the stronger.

The little old man, one yard high, with a beard seven yards long, began to pray and to beg,â

“O man of power, O great and mighty bogatir, have mercy upon me. Do not kill me. Leave me my soul to repent with.”

Sunrise laughed, and dragged the little fellow out into the yard, whirled him round at the end of his beard, and brought him to a great oak trunk that lay on the ground. Then with a heavy iron wedge he fixed the end of the little man's beard firmly in the oaken trunk, and, leaving the little man howling and lamenting, went back to the hut, set it in order again, saw that the sheep was cooking as it should, and then lay down in peace to wait for the coming of his brothers.

Evening and Midnight rode home, leapt from their horses, and came into the hut to see how the little man had dealt with their brother. They could hardly believe their eyes when they saw him alive and well, without a bruise, lying comfortably on the bench.

He sat up and laughed in their faces.

“Well, brothers,” says he, “come along with me into the yard, and I think I can show you that headache of yours. It's a good deal stronger than it is big, but for the time being you need not be afraid of it, for it's fastened to an oak timber that all three of us together could not lift.”

He got up and went into the yard. Evening and Midnight followed him with shamed faces. But when they came to the oaken timber the little man was not there. Long ago he had torn himself free and run away into the forest. But half his beard was left, wedged in the trunk, and Sunrise pointed to that and said,â

“Tell me, brothers, was it the heat of the stove that gave you your headaches? Or had this long beard something to do with it?”

The brothers grew red, and laughed, and told him the whole truth.

Meanwhile Sunrise had been looking at the end of the beard, the end of the half beard that was left, and he saw that it had been torn out by the roots, and that drops of blood from the little man's chin showed the way he had gone.

Quickly the brothers went back to the hut and ate up the sheep. Then they leapt on their horses, and rode off into the green forest, following the drops of blood that had fallen from the little man's chin. For three days they rode through the green forest, until at last the red drops of the trail led them to a deep pit, a black hole in the earth, hidden by thick bushes and going far down into the underworld.

Sunrise left his brothers to guard the hole, while he went off into the forest and gathered bast, and twisted it, and made a strong rope, and brought it to the mouth of the pit, and asked his brothers to lower him down.

He made a loop in the rope. His brothers kissed him on both cheeks, and he kissed them back. Then he sat in the loop, the Evening and Midnight lowered him down into the darkness. Down and down he went, swinging in the dark, till he came into a world under the world, with a light that was neither that of the sun, nor of the moon, nor of the stars. He stepped from the loop in the rope of twisted bast, and set out walking through the underworld, going whither his eyes led him, for he found no more drops of blood, nor any other traces of the little old man.

He walked and walked, and came at last to a palace of copper, green and ruddy in the strange light. He went into that palace, and there came to meet him in the copper halls a maiden whose cheeks were redder than the aloe and whiter than the snow. She was the youngest daughter of the King, and the loveliest of the three princesses, who were the loveliest in all the world. Sweetly she curtsied to Sunrise, as he stood there with his golden hair and his eyes blue as the sky at morning, and sweetly she asked him,â

“How have you come hither, my brave young manâof your own will or against it?”

“Your father has sent to rescue you and your sisters.”

She bade him sit at the table, and gave him food and brought him a little flask of the water of strength.

“Strong you are,” says she, “but not strong enough for what is before you. Drink this, and your strength will be greater than it is; for you will need all the strength you have and can win, if you are to rescue us and live.”

Sunrise looked in her sweet eyes, and drank the water of strength in a single draught, and felt gigantic power forcing its way throughout his body.

“Now,” thought he, “let come what may.”

Instantly a violent wind rushed through the copper palace, and the Princess trembled.

“The snake that holds me here is coming,” says she. “He is flying hither on his strong wings.”

She took the great hand of the bogatir in her little fingers, and drew him to another room, and hid him there.

The copper palace rocked in the wind, and there flew into the great hall a huge snake with three heads. The snake hissed loudly, and called out in a whistling voice,â

“I smell the smell of a Russian soul. What visitor have you here?”

“How could any one come here?” said the Princess. “You have been flying over Russia. There you smelt Russian souls, and the smell is still in your nostrils, so that you think you smell them here.”

“It is true,” said the snake: “I have been flying over Russia. I have flown far. Let me eat and drink, for I am both hungry and thirsty.”

All this time Sunrise was watching from the other room.

The Princess brought meat and drink to the snake, and in the drink she put a philtre of sleep.

The snake ate and drank, and began to feel sleepy. He coiled himself up in rings, laid his three heads in the lap of the Princess, told her to scratch them for him, and dropped into a deep sleep.

The Princess called Sunrise, and the bogatir rushed in, swung his glittering sword three times round his golden head, and cut off all three heads of the snake. It was like felling three oak trees at a single blow. Then he made a great fire of wood, and threw upon it the body of the snake, and, when it was burnt up, scattered the ashes over the open country.

“And now fare you well,” says Sunrise to the Princess; but she threw her arms about his neck.

“Fare you well,” says he. “I go to seek your sisters. As soon as I have found them I will come back.”

And at that she let him go.

He walked on further through the underworld, and came at last to a palace of silver, gleaming in the strange light.

He went in there, and was met with sweet words and kindness by the second of the three lovely princesses. In that palace he killed a snake with six heads. The Princess begged him to stay; but he told her he had yet to find her eldest sister. At that she wished him the help of God, and he left her, and went on further.

He walked and walked, and came at last to a palace of gold, glittering in the light of the underworld. All happened as in the other palaces. The eldest of the three daughters of the King met him with courtesy and kindness. And he killed a snake with twelve heads and freed the Princess from her imprisonment. The Princess rejoiced, and thanked Sunrise, and set about her packing to go home.

And this was the way of her packing. She went out into the broad courtyard and waved a scarlet handkerchief, and instantly the whole palace, golden and glittering, and the kingdom belonging to it, became little, little, little, till it went into a little golden egg. The Princess tied the egg in a corner of her handkerchief, and set out with Sunrise to join her sisters and go home to her father.

Her sisters did their packing in the same way. The silver palace and its kingdom were packed by the second sister into a little silver egg. And when they came to the copper palace, the youngest of the three lovely princesses clapped her hands and kissed Sunrise on both his cheeks, and waved a scarlet handkerchief, and instantly the copper palace and its kingdom were packed into a little copper egg, shining ruddy and green.

And so Sunrise and the three daughters of the King came to the foot of the deep hole down which he had come into the underworld. And there was the rope hanging with the loop at its end. And they sat in the loop, and Evening and Midnight pulled them up one by one, rejoicing together. Then the three brothers took, each of them, a princess with him on his horse, and they all rode together back to the old King, telling tales and singing songs as they went. The Princess from the golden palace rode with Evening on his horse of dusky brown; the Princess from the silver palace rode with Midnight on his horse as black as charcoal; but the Princess from the copper palace, the youngest of them all, rode with Sunrise on his horse, white as a summer cloud. Merry was the journey through the green forest, and gladly they rode over the open plain, till they came at last to the palace of her father.

There was the old King, sitting melancholy alone, when the three brothers with the princesses rode into the courtyard of the palace. The old King was so glad that he laughed and cried at the same time, and his tears ran down his beard.

“Ah me!” says the old King, “I am old, and you young men have brought my daughters back from the very world under the world. Safer they will be if they have you to guard them, even than they were in the palace I had built for them underground. But I have only one kingdom and three daughters.”

“Do not trouble about that,” laughed the three princesses, and they all rode out together into the open country, and there the princesses broke their eggs, one after the other, and there were the palaces of silver, copper, and gold, with the kingdoms belonging to them, and the cattle and the sheep and the goats. There was a kingdom for each of the brothers. Then they made a great feast, and had three weddings all together, and the old King sat with the mother of the three strong men, and men of power, the noble bogatirs, Evening, Midnight, and Sunrise, sitting at his side. Great was the feasting, loud were the songs, and the King made Sunrise his heir, so that some day he would wear his crown. But little did Sunrise think of that. He thought of nothing but the youngest Princess. And little she thought of it, for she had no eyes but for Sunrise. And merrily they lived together in the copper palace. And happily they rode together on the horse that was as white as clouds in summer.

ONCE UPON a time there was a widowed old man who lived alone in a hut with his little daughter. Very merry they were together, and they used to smile at each other over a table just piled with bread and jam. Everything went well, until the old man took it into his head to marry again.

Yes, the old man became foolish in the years of his old age, and he took another wife. And so the poor little girl had a stepmother. And after that everything changed. There was no more bread and jam on the table, and no more playing bo-peep, first this side of the samovar and then that, as she sat with her father at tea. It was worse than that, for she never did sit at tea. The stepmother said that everything that went wrong was the little girl's fault. And the old man believed his new wife, and so there were no more kind words for his little daughter. Day after day the stepmother used to say that the little girl was too naughty to sit at table. And then she would throw her a crust and tell her to get out of the hut and go and eat it somewhere else.

And the poor little girl used to go away by herself into the shed in the yard, and wet the dry crust with her tears, and eat it all alone. Ah me! she often wept for the old days, and she often wept at the thought of the days that were to come.

Mostly she wept because she was all alone, until one day she found a little friend in the shed. She was hunched up in a corner of the shed, eating her crust and crying bitterly, when she heard a little noise. It was like this: scratchâscratch. It was just that, a little gray mouse who lived in a hole.

Out he came, his little pointed nose and his long whiskers, his little round ears and his bright eyes. Out came his little humpy body and his long tail. And then he sat up on his hind legs, and curled his tail twice round himself and looked at the little girl.

The little girl, who had a kind heart, forgot all her sorrows, and took a scrap of her crust and threw it to the little mouse. The mouseykin nibbled and nibbled, and there, it was gone, and he was looking for another. She gave him another bit, and presently that was gone, and another and another, until there was no crust left for the little girl. Well, she didn't mind that. You see, she was so happy seeing the little mouse nibbling and nibbling.

When the crust was done the mouseykin looks up at her with his little bright eyes, and “Thank you,” he says, in a little squeaky voice. “Thank you,” he says; “you are a kind little girl, and I am only a mouse, and I've eaten all your crust. But there is one thing I can do for you, and that is to tell you to take care. The old woman in the hut (and that was the cruel stepmother) is own sister to Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch. So if ever she sends you on a message to your aunt, you come and tell me. For Baba Yaga would eat you soon enough with her iron teeth if you did not know what to do.”

“Oh, thank you,” said the little girl; and just then she heard the stepmother calling to her to come in and clean up the tea things, and tidy the house, and brush out the floor, and clean everybody's boots.

So off she had to go.

When she went in she had a good look at her stepmother, and sure enough she had a long nose, and she was as bony as a fish with all the flesh picked off, and the little girl thought of Baba Yaga and shivered, though she did not feel so bad when she remembered the mouseykin out there in the shed in the yard.

The very next morning it happened. The old man went off to pay a visit to some friends of his in the next village. And as soon as the old man was out of sight the wicked stepmother called the little girl.

“You are to go to-day to your dear little aunt in the forest,” says she, “and ask her for a needle and thread to mend a shirt.”

“But here is a needle and thread,” says the little girl.

“Hold your tongue,” says the stepmother, and she gnashes her teeth, and they make a noise like clattering tongs. “Hold your tongue,” she says. “Didn't I tell you you are to go to-day to your dear little aunt to ask for a needle and thread to mend a shirt?”

“How shall I find her?” says the little girl, nearly ready to cry, for she knew that her aunt was Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch.

The stepmother took hold of the little girl's nose and pinched it.

“That is your nose,” she says. “Can you feel it?”

“Yes,” says the poor little girl.

“You must go along the road into the forest till you come to a fallen tree; then you must turn to your left, and then follow your nose and you will find her,” says the stepmother. “Now, be off with you, lazy one. Here is some food for you to eat by the way.” She gave the little girl a bundle wrapped up in a towel.

The little girl wanted to go into the shed to tell the mouseykin she was going to Baba Yaga, and to ask what she should do. But she looked back, and there was the stepmother at the door watching her. So she had to go straight on.

She walked along the road through the forest till she came to the fallen tree. Then she turned to the left. Her nose was still hurting where the stepmother had pinched it, so she knew she had to go straight ahead. She was just setting out when she heard a little noise under the fallen tree.

“Scratchâscratch.”

And out jumped the little mouse, and sat up in the road in front of her.

“O mouseykin, mouseykin,” says the little girl, “my stepmother has sent me to her sister. And that is Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch, and I do not know what to do.”

“It will not be difficult,” says the little mouse, “because of your kind heart. Take all the things you find in the road, and do with them what you like. Then you will escape from Baba Yaga, and everything will be well.”

“Are you hungry, mouseykin?” said the little girl.

“I could nibble, I think,” says the little mouse.

The little girl unfastened the towel, and there was nothing in it but stones. That was what the stepmother had given the little girl to eat by the way.

“Oh, I'm so sorry,” says the little girl. “There's nothing for you to eat.”

“Isn't there?” said mouseykin, and as she looked at them the little girl saw the stones turn to bread and jam. The little girl sat down on the fallen tree, and the little mouse sat beside her, and they ate bread and jam until they were not hungry any more.

“Keep the towel,” says the little mouse; “I think it will be useful. And remember what I said about the things you find on the way. And now good-bye,” says he.

“Good-bye,” says the little girl, and runs along.

As she was running along she found a nice new handkerchief lying in the road. She picked it up and took it with her. Then she found a little bottle of oil. She picked it up and took it with her. Then she found some scraps of meat.

“Perhaps I'd better take them too,” she said; and she took them.

Then she found a gay blue ribbon, and she took that. Then she found a little loaf of good bread, and she took that too.

“I daresay somebody will like it,” she said.

And then she came to the hut of Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch. There was a high fence round it with big gates. When she pushed them open they squeaked miserably, as if it hurt them to move. The little girl was sorry for them.

“How lucky,” she says, “that I picked up the bottle of oil!” and she poured the oil into the hinges of the gates.

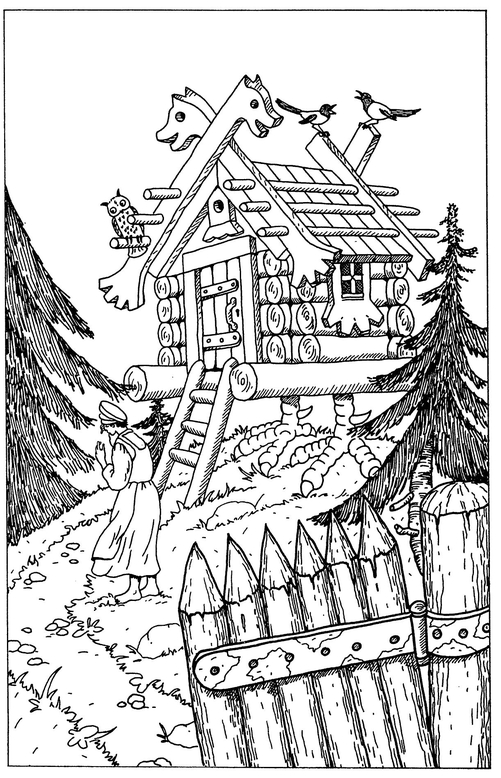

Inside the railing was Baba Yaga's hut, and it stood on hen's legs and walked about the yard. And in the yard there was standing Baba Yaga's servant, and she was crying bitterly because of the tasks Baba Yaga set her to do. She was crying bitterly and wiping her eyes on her petticoat.

Baba Yaga's hut stood on hen's legs and walked about the yard.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up a handkerchief!” And she gave the handkerchief to Baba Yaga's servant, who wiped her eyes on it and smiled through her tears.

Close by the hut was a huge dog, very thin, gnawing a dry crust.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up a loaf!” And she gave the loaf to the dog, and he gobbled it up and licked his lips.

The little girl went bravely up to the hut and knocked on the door.

“Come in,” says Baba Yaga.

The little girl went in, and there was Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch, sitting weaving at a loom. In a corner of the hut was a thin black cat watching a mouse-hole.

“Good-day to you, auntie,” says the little girl, trying not to tremble.

“Good-day to you, niece,” says Baba Yaga.

“My stepmother has sent me to you to ask for a needle and thread to mend a shirt.”

“Very well,” says Baba Yaga, smiling, and showing her iron teeth. “You sit down here at the loom, and go on with my weaving, while I go and get you the needle and thread.”

The little girl sat down at the loom and began to weave.

Baba Yaga went out and called to her servant, “Go, make the bath hot and scrub my niece. Scrub her clean. I'll make a dainty meal of her.”

The servant came in for the jug. The little girl begged her, “Be not too quick in making the fire, and carry the water in a sieve.” The servant smiled, but said nothing, because she was afraid of Baba Yaga. But she took a very long time about getting the bath ready.

Baba Yaga came to the window and asked,â

“Are you weaving, little niece? Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the little girl.

When Baba Yaga went away from the window, the little girl spoke to the thin black cat who was watching the mouse-hole.

“What are you doing, thin black cat?”

“Watching for a mouse,” says the thin black cat. “I haven't had any dinner for three days.”

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up the scraps of meat!” And she gave them to the thin black cat. The thin black cat gobbled them up, and said to the little girl,â

“Little girl, do you want to get out of this?”

“Catkin dear,” says the little girl, “I do want to get out of this, for Baba Yaga is going to eat me with her iron teeth.”

“Well,” says the cat, “I will help you.”

Just then Baba Yaga came to the window.

“Are you weaving, little niece?” she asked. “Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the little girl, working away, while the loom went clickety clack, clickety clack.

Baba Yaga went away.

Says the thin black cat to the little girl: “You have a comb in your hair, and you have a towel. Take them and run for it while Baba Yaga is in the bath-house. When Baba Yaga chases after you, you must listen; and when she is close to you, throw away the towel, and it will turn into a big, wide river. It will take her a little time to get over that. But when she does, you must listen; and as soon as she is close to you throw away the comb, and it will sprout up into such a forest that she will never get through it at all.”

“But she'll hear the loom stop,” says the little girl.

“I'll see to that,” says the thin black cat.

The cat took the little girl's place at the loom.

Clickety clack, clickety clack; the loom never stopped for a moment.

The little girl looked to see that Baba Yaga was in the bath-house, and then she jumped down from the little hut on hen's legs, and ran to the gates as fast as her legs could flicker.

The big dog leapt up to tear her to pieces. Just as he was going to spring on her he saw who she was.

“Why, this is the little girl who gave me the loaf,” says he. “A good journey to you, little girl;” and he lay down again with his head between his paws.

When she came to the gates they opened quietly, quietly, without making any noise at all, because of the oil she had poured into their hinges.

Outside the gates there was a little birch tree that beat her in the eyes so that she could not go by.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up the ribbon!” And she tied up the birch tree with the pretty blue ribbon. And the birch tree was so pleased with the ribbon that it stood still, admiring itself, and let the little girl go by.

How she did run!

Meanwhile the thin black cat sat at the loom. Clickety clack, clickety clack, sang the loom: but you never saw such a tangle as the tangle made by the thin black cat.

And presently Baba Yaga came to the window.

“Are you weaving, little niece?” she asked. “Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the thin black cat, tangling and tangling, while the loom went clickety clack, clickety clack.

“That's not the voice of my little dinner,” says Baba Yaga, and she jumped into the hut, gnashing her iron teeth; and there was no little girl, but only the thin black cat, sitting at the loom, tangling and tangling the threads.

“Grr,” says Baba Yaga, and jumps for the cat, and begins banging it about. “Why didn't you tear the little girl's eyes out?”