The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder and the Birth of the American Mafia (32 page)

Read The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder and the Birth of the American Mafia Online

Authors: Mike Dash

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #History, #Espionage, #Organized Crime, #Murder, #Social Science, #True Crime, #United States - 20th Century (1900-1945), #Turn of the Century, #Mafia, #United States - 19th Century, #United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Criminals, #Biography, #Serial Killers, #Social History, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Criminology

The Clutch Hand and his followers, a newsman from the

Sun

observed, were shaken to the core by Comito’s unexpected appearance in the witness box. They “had not heard of his falling into the hands of the Secret Service men, and when he was sworn in as a witness against them … the glares of the eight men in the prisoners’ row were not calculated to lend him encouragement.” As Flynn had planned, though, it was far too late by then to stop the printer from testifying. Desperate measures were certainly attempted—a price of $2,500 was placed on the Calabrian’s head only hours after he began his testimony, and Mirabeau Towns, in cross-examination, did his best to portray Comito as a bloodthirsty outlaw, a Calabrian bandit of some infamy now heavily involved in the white slave trade whose sworn testimony could not be trusted. In the absence of a single witness to back up Towns, however, such suggestions had little chance of doing damage.

There were few bright spots in the case thereafter for the Morello family. The Clutch Hand himself chose not to give evidence, as did Antonio Cecala, and though Lupo did testify in his own defense, nothing he said disproved Comito’s allegations. Romano and Brancatto both appeared, and both men gave their evidence as promised, but the massed statements of Flynn’s operatives reduced the doctors’ testimony to tatters. Detailed notes of dates and times, read carefully from notebooks, weighed a good deal more heavily with judge and jury than the vague statements of two Italians, however qualified, and the alibi that Morello and Nick Terranova had constructed with such care was shattered. Both Romano and Brancatto would eventually be charged with perjury.

Well over sixty witnesses were called in all, and though most barely detained the court (Lupo’s wife was on the stand for less than a minute), Comito’s testimony alone took so long to give that it was not until February 19 that Judge Ray brought the proceedings to a close, formally delivering his charge and sending the jury out to consider its judgment. In complicated cases, as Morello realized, a lengthy sequestration frequently indicated a “not guilty” verdict, and when the jury filed back in after a mere forty-five minutes’ deliberation, both the Clutch Hand and the Wolf wore the haunted look of criminals expecting a conviction. But there was still hope even then. Both men knew that the punishments for counterfeiting were seldom severe. Since Flynn had taken charge in New York, they had generally run to less than a year for a first offense and three to five years for the leaders of a gang. With time allowed for good behavior, even the harshest of those sentences would mean spending little more than three years in jail.

It became clear almost at once, though, that this case was to be quite different. Judge Ray had taken the precaution of having the court cleared of spectators while the jury was at lunch, leaving only officials and reporters present as a long series of guilty verdicts was read. Even so, shocked murmurs rippled through the room as the defendants came forward, one by one, to hear their sentences pronounced.

Giuseppe Morello, Ray intoned: twenty-five years’ hard labor and a thousand-dollar fine.

Lupo, thirty years and the same fine as Morello.

The remaining sentences were just as harsh. Calicchio, the master printer, got seventeen years in jail, Cina a year more than that. Cecala, Giglio, and Nick Sylvester all received sentences of fifteen years. More than a century and a half of servitude in all, to be served in the forbidding fortress prison of Atlanta.

Flynn would claim, in later years, that Judge Ray had been made well aware of Morello’s lengthy record—the arrests as well as the convictions, the murders as well as the nonviolent crimes—and that his judgment took into account the Mafioso’s guilt in the matter of the Barrel Murder. Whether that was true or not—the terms imposed were all severe, though only Lupo and Morello had been involved in the Madonia affair—the sentences were by far the longest ever handed down for counterfeiting by a U.S. court. “The words of the judge,” the

American

reported, “seemed to strike the prisoners down like pistol shots.”

Calicchio, who was the first man called before Judge Ray, appeared to have aged well beyond his fifty-two years, and he listened in silence as the court interpreter explained his sentence. Then, as the verdict sank in, the old forger began to scream, loudly and unceasingly, drowning out every attempt to quiet him. After a few moments of this unearthly wailing, officials were forced to half lead, half carry the prisoner to the holding cells, his yells echoing back along the corridors as he was dragged away. Calicchio’s bubbling wails could still be heard through several doors as Morello was summoned, and the Clutch Hand seemed unnerved by the printer’s performance. He slid rather than walked to the bar, and trembled as his sentence was pronounced.

Morello’s English was good enough for him to understand the judge’s words without the aid of an interpreter, and his response was just as dramatic as Calicchio’s. As Ray set out his sentence, New York’s most feared Mafia boss dropped to the floor in a faint, then, half reviving, went into convulsions. Whether or not his collapse was an act intended to wring sympathy from the court—most of the disgusted newsmen present thought it was—he too had to be helped up and hustled from the room. Lupo, for his part, began sobbing as he stood before the judge and, by the time he had finished pleading for mercy, had “used up one whole handkerchief with his tears.” The Wolf then stood, seemingly catatonic, while his thirty-year punishment was explained.

The shock of the heavy sentences was just as severely felt in the corridor outside, where word of the record terms, and the sound of groans and sobbing from the courtroom, set off furious mutterings among the friends and relatives of the convicted Mafiosi. U.S. Marshal William Henkel, in charge of security in court, had mustered nearly seventy men—thirty-five of his own officers, a dozen Secret Service agents, fifteen detectives, and six uniformed policemen—and all of them were needed to keep order as the news emerged. Henkel had to order that the corridor be cleared four or five times before things quieted down sufficiently for the prisoners to be manacled and marched away, and the short walk to the holding cells in the Tombs prison on Centre Street was a nervous one. Fully expecting that they might become a target for the remaining members of Morello’s family, marshals and Secret Service men alike flinched as the press photographers outside discharged blinding volleys of flashbulbs. A brief panic ensued when a weaving drunk blundered into the column and appeared intent on breaking through to reach the prisoners.

It was pitch dark and freezing by the time the massive prison gates were reached. Henkel’s marshals stopped the traffic on the street, holding up two streetcars, three women with five babies, and a weeping crowd of relatives while the prisoners were ushered inside. Flynn stepped forward and answered a few questions, glad to reap the praise to which his years of unceasing effort had entitled him. “That will help some,” the Chief remarked with a half smile as the gates thudded shut—just the sort of understated comment that the press loved hearing from a Secret Service man. His words made most of the next day’s papers.

CHAPTER 11

MOB

T

HE PRISON THAT WAS TO HOUSE MORELLO AND LUPO FOR THE

next twenty years or more rose behind imposing walls to the southeast of Atlanta. It was the most important federal prison in America, and suitably enormous—the biggest concrete structure in the world. From outside, it looked more like a medieval castle than a prison, but appearances, in this case, were deceptive. The jail was still more or less brand new—the first group of convicts had arrived only in 1902—and its warden liked to paint it as a model institution. It was certainly better appointed than the state prisons the Morello gang had left behind them in New York, and was not designed to grind down its inmates’ wills or break their spirits, as Sing Sing had been and in some respects still was. Prisoners were spared the rock breaking that constituted hard labor in other penitentiaries, being set instead to “useful tasks.” Morello was assigned to the tailors’ shop. Even more remarkably, the men worked “union hours,” which meant an eight-hour day rather than the back-breaking dawn-to-dusk routine followed on the chain gangs then commonplace elsewhere in Georgia. After work, they returned each night to blocks that held a total of just eight hundred prisoners, mostly one man to a cell—an unheard-of luxury to other jails.

Discipline was strict but rarely violent. Corporal punishment did not exist; troublemakers received spells of solitary confinement on a restricted diet. Even the food was good, though there were none of the Italian staples that Morello and his followers pined for—”no spaghetti or garlic,” a sneering journalist informed his readers. Inmates received three square meals a day: perhaps fish cakes, bread, and coffee at breakfast time, beef stew for lunch, and doughnuts or fried potatoes in the evening. Conditions were so marvelous, a reporter from

The Washington

Post

was told, that one prisoner, recently released, had smashed open a mailbox just to get himself arrested and returned to jail.

It was not the jail itself, in fact, but the sheer length of the sentences confronting them that weighed on the Sicilians’ minds. Allowing for time off for good behavior, the earliest date that Morello would be considered for release was December 4, 1926, nearly seventeen years away. For Lupo the Wolf it was more than three years later: April 3, 1930. The sentences, Morello complained in a letter to his wife, were “enough to drive a man crazy.”

What kept the prisoners sane, for the first year at least, was the hope that their appeal would be allowed. The remaining members of the Morello family worked hard to make that possible, and their prospects of achieving something improved immeasurably when they retained Bourke Cockran, a celebrated litigator and one of the highest-paid defense attorneys in the country. They raised the money required to pay him through the usual “appropriations” in East Harlem—where pushcart peddlers, merchants, and petty bankers were terrorized into handing over contributions—and in gifts sent by other Mafia families from as far away as Tunis; at one point the fund raised in this way stood at fifty thousand dollars, a portion of which was set aside to bribe witnesses from the first trial to change their stories. The Terranovas did what they could to bring political pressure to bear at the same time, and their influence in Harlem was such that both Republicans and Democrats seemed ready to help. All those efforts, though, counted for little when the case actually reached the appeals court. Flynn’s case was just too watertight. The appeal was heard and dismissed in June 1911, and Cockran’s fees were so enormous that there was no money left afterward to mount another attempt.

Thwarted though they had been in the courts, the remaining members of Morello’s gang did not altogether give up hope. John Lupo, the brother of the Wolf, cultivated contacts in the Catholic Church in the hope of obtaining a recommendation for mercy from New York’s Cardinal Gibbons. Another scheme that the Terranovas seriously considered was to have Morello accept full responsibility for organizing the counterfeiting operation, in the hope that Lupo might then be freed; the brothers believed, Flynn noted, “that once Lupo is out, they would have a better chance to get Morello out.” This plan was abandoned almost as soon as it was explained to the Clutch Hand during a family visit to the penitentiary. According to William Moyer, Atlanta’s warden, who had stationed guards and an interpreter within earshot, “it affected him so much that the Deputy Warden was obliged to relieve him from work and assign him to his cell, because he appeared to be mentally as well as physically in no condition to work, in other words this plan seemed to break Morello.”

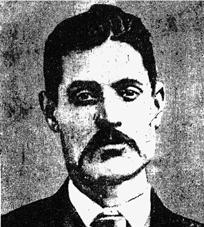

Giuseppe Morello, first “boss of bosses” of the American Mafia, is forced to display the deformed, one-fingered hand that earned him the nickname “the Clutch Hand” in this 1900 mugshot. According to Secret Service files, Morello personally committed two murders and ordered at least sixty more. Even the influential second-generation Mafia boss Joe Bonanno was terrified of him: “There was nothing of the buffoon about Morello. He had a parched, gaunt voice, a stone face and a claw.”

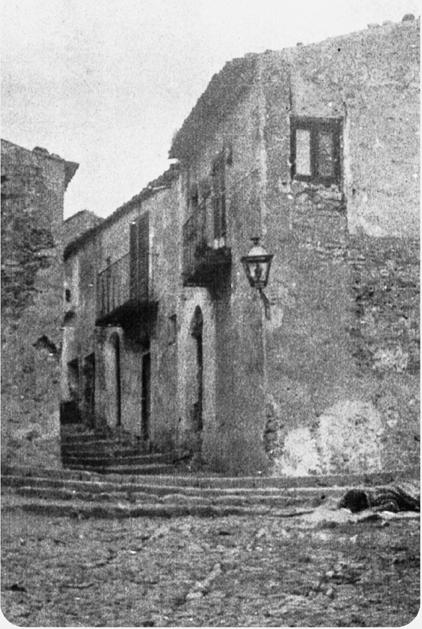

A street scene in Corleone. The Sicilian town—notorious even in the nineteenth century as one of the Mafia’s great strongholds—was home to Morello and his brothers. The body lying facedown on the right with eleven bullets in it is that of Bernardino Verro, Corleone’s mayor. Verro, who—to his lasting shame—was initiated into the Mafia by Morello’s stepfather, paid the ultimate price for denouncing the society.

Don Vito Cascio Ferro, Morello’s ally in New York, became the greatest leader that the Sicilian Mafia ever produced. “Every mayor, dressed in his best clothes, awaited him at the entrance to his village, kissed his hands, and paid homage as if he were the king.”

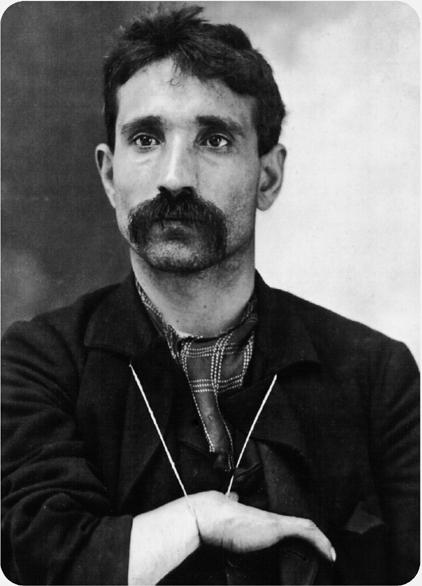

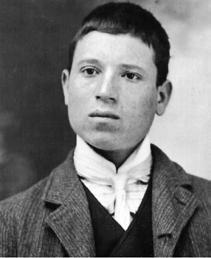

Calogero Maggiore. A mere twenty years old, and a “shirt ironer” by trade, the young Sicilian was persuaded by Giuseppe Morello to front an early counterfeiting scheme. When the ring was broken up by the Secret Service in June 1900, Maggiore went to prison for six years; Morello walked free.

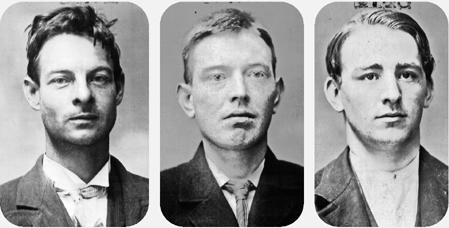

More Morello dupes: three of the Irish petty criminals picked up by the NYPD in the summer of 1900 for “queer pushing.” They are

(left to right)

Chas Brown (alias Steve Sullivan), John “Red” Duffy, and Edward R. Kelly.

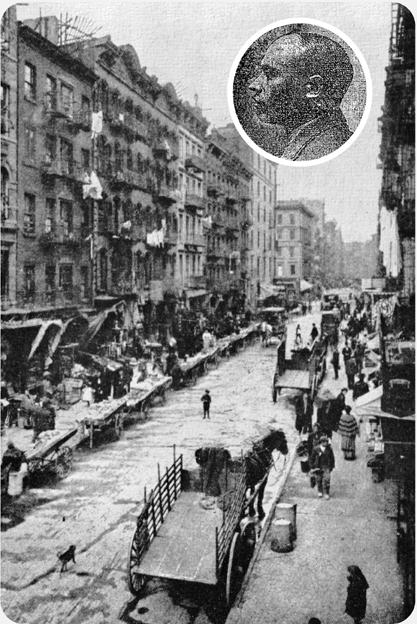

Bustling Little Italy in the early days of the century. The first Italian crime boss to gain control of the immigrant quarter was Giuseppe D’Agostino

(inset)

who used a chain of grocery stores as a front for a vast extortion ring. D’Agostino was forcibly “retired” by the Morello family in 1902 as the Mafia established itself and the Sicilians promptly took control of his grocery rackets.