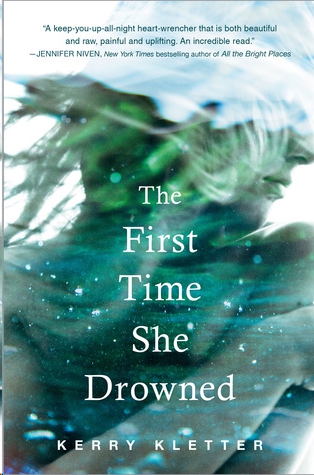

The First Time She Drowned

Read The First Time She Drowned Online

Authors: Kerry Kletter

Tags: #Young Adult Fiction, #Social Themes, #Depression, #Family, #Parents, #Sexual Abuse

P

H

ILOMEL

B

OOKS

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Copyright © 2016 by Kerry Kletter.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Philomel Books is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

eBook ISBN 978-0-698-18893-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kletter, Kerry.

The first time she drowned / Kerry Kletter.

pages cm

Summary: Committed to a mental hospital against her will for something she claims she did not do, Cassie O’Malley signs herself out against medical advice when she turns eighteen and tries to start over at college, until her estranged mother appears, throwing everything Cassie believes about herself into question.

[1. Self-actualization (Psychology)—Fiction. 2. Emotional problems—Fiction. 3. Family problems—Fiction. 4. Mothers and daughters—Fiction. 5. Memory—Fiction. 6. Sexual abuse—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.1.K65Fir 2016

[Fic]—dc23

2014045881

ISBN 978-0-399-17103-1

Edited by Liza Kaplan.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

To Beth Macdonald and Susan Nagin Thau for everything.

In Memory of John.

MY MOTHER WORE

the sun like a hat. It followed her as we did, stopping when she stopped, moving when she moved. She carried her beauty with the naiveté of someone who was born to it and thus never understood its value or the poverty of ugliness.

As children, my older brother, Matthew, and I were drawn to her like tides, always reaching our arms up to her, pulled to her light. If she had shadows, I did not recognize them as such. I saw her only in her most perfect form, and any suggestion of coldness or unkindness was merely a reflection of me. This was the unspoken agreement I had with her, suspiciously drawn up before I was old enough to understand its cost.

Until I was a teenager, my family lived on the poor side of a wealthy town in Pennsylvania. It was a washed-out-looking neighborhood where the colors of the houses were tired and peeling from neglect. Still, we had a huge backyard that stretched wide and ripe with all things wonderful to children. On its left seam it was lined with blackberry bushes whose purple juices stained our fingers as we stuffed them into jars for jam. On the right and perched tenuously on a hill as if cresting a wave of green sat an enormous yellow boat, so old and weathered, it had undoubtedly crawled its way to the shores of our yard to die. The boat was as big as our house and about as seaworthy. When

I once asked my mother why we bothered to keep it, she looked not at the boat but at my father, who was tooling uselessly about its deck.

“It’s a fixer-upper for sure,” she’d said. “But maybe there’s something we can salvage.” She didn’t sound very convincing.

If nothing else, the boat was the perfect venue for playing pirates. Every weekend, Matthew, who loved to wield his authority in being three years older, played the role of the good captain while I, in a flash of prescience, was relegated to the part of the doomed and hated buccaneer. He would order me to move here and there, serving as both actor and director of our little scenes, and I would follow his instructions dutifully because Matthew was always better at pretending than I was.

Meanwhile, my father cleaned and fussed with the old boat, muttering and sighing as if his repetitive efforts might someday induce its spirit back to life. My brother and I would race wildly around him, as heedless of his frustrated cursing—the background noise of our childhood—as he was to our presence. For it was not for him that we played and scrambled about, maybe not even always for ourselves, but for her, the one who wore the sun like a hat, who was the sun to us. Because she mattered more. And because I sensed on some subterranean level that she needed us to, sensed that if we did not play the role of happy children, she might break like the Atlantic upon us.

Yet, for all my efforts, there were moments when I would catch my mother looking at that broken boat with the strange and startled horror of the drowning. This frightened me, and always I looked to Matthew to see if he too noticed the seas rising behind

my mother’s eyes. He did not. Or if he did, he did not acknowledge it. But I saw too much. And I was never as good at pretending as Matthew was.

DR. MEEKS’S OFFICE

is on the other side of the hospital and sometimes, if the weather is decent and the nurse escorting me is kind, we take the outside route to get there. I see him on Tuesdays and Thursdays and it’s a five-minute walk, so if I’m lucky, I get ten extra minutes of sunlight on top of the four hours we are permitted each week. By comparison, even murderers on death row get out more than that. I know this because James and I looked it up. I once complained to Meeks that my vitamin D level is probably dangerously low, and he replied that if I’m so concerned about my health, I shouldn’t smoke so many cigarettes. I told him I smoke only because there is nothing else to do—which there isn’t. He suggested I could be “spending my time working on myself.” I told him I refused to take advice from a man who wears jazz shoes and a fake orange tan. Ever since Meeks agreed to have me committed here for something I didn’t do—something that never even happened—we haven’t gotten along so well.

The hospital grounds are lush and vast with grass the color of Ireland. The beauty is not for the patients but for the visitors, to protect them from the bleak, stretched-time despair behind the façade. It’s like the white picket fence that masks the ugly truth of a suburban family. Or in my case, the sprawling lawn, the sunlit mother, the large boat that doesn’t actually sail.

Those of us inside the hospital walls spend most of our time

staring out of locked windows with steel mesh screens at all that beauty we cannot have. But today on the way to Meeks’s office, the outside world feels different, like something that belongs to me too, not just a piece of sky I get to borrow for four hours a week from a nurse with keys. I have just turned eighteen, old enough to sign myself out of here AMA—Against Medical Advice. Yesterday I turned in my seventy-two-hour notice, which means I will be leaving this hellhole in two days. Two days. Hallelujah.

Nurse Mary and I enter the waiting room with its beige and brown tones and the single, uninspired painting on the wall of a small child with her back to the observer, playing in the sand. All of the decor is designed to soothe, or at least not provoke. It’s just one of the many insidious ways they suck the spirit out of you in here, make everything so bland and dull that your limbic system just shrivels up like a raisin and dies.

Dr. Meeks cracks open the door to his office and sticks his big llama head out. “Cassie,” he says in the same morose way he always says it, like he’s about to show me a dead body. He has tight curly hair and milk-white teeth and looks like a second-rate game show host on cable. He opens the door wide and I walk past him to the couch, sit down and wait for this to be over. One last session and I’ll never have to see him again.

“So. You’re really going through with this,” he says.

For the past two and a half years I have hardly looked at him, fearing that to allow even a moment of connection is to risk breaking, just like most of the other kids here. But today I look directly into Dr. Meeks’s eyes, and when I do, my whole center of gravity shifts, moves lower like a stake in the ground, making

me sturdy and immovable. He has no power left. “Try not to miss me too much.”

“I still wish you’d reconsider,” he says. “I’m worried about you.” But he doesn’t look worried. He looks irritated that I have refused to accept his diagnosis that I am sick and in need of the medicine he’s been trying to shove down my throat for the last two and a half years. “You haven’t really addressed your problems here.”

“What problems?” I say. I’ve already explained to him that the biggest problem I have is people like him believing that I’m the problem. But he won’t see the truth. None of them will. Adults always believe the parents over the kid, it’s a fact of life.

“For instance . . . you still haven’t talked to me about your nightmares.”

Just the mention of my nightmares makes something seize up inside of me. But there’s no way in hell I’d ever talk to Meeks about them. Or about anything else for that matter. I pull a loose thread of fabric from my shirt and examine it with my fingers. All I have to do is sit here quietly and bide my time for one hour and I’ll never have to do this again.

“I wish we had more time,” he continues, “to develop a trusting relationship.”

“Trust?” I say with a laugh. I know it’s not even worth engaging at this point, but it’s just so irritating. “Maybe if you’d tried listening to me instead of falling for my mother’s—”

“Cassie, your mother loves you. She brought you to us because she wanted you to get well. We all do.”

I shoot forward, unable to stop myself. “Really? My mother loves me? ’Cause you’ve said that before and I’m curious: what has

she ever done to make you think that?”

“Cassie . . .”

“I mean, putting aside the vicious lies—is it the once every, what, six months that she managed to visit? The letters she never wrote, the phone calls she never made?”

“Cassie.”

“Or is it just that you’ve fallen for the myth that all mothers love their children?” As if all people feel the same way about anything. As if there’s only one feeling you can have. “I’m being serious here, because maybe there’s something I’m missing. I need to know why—”

“You don’t know what you need, Cassie!” he fires back.

I put my hands up and fall back into the couch again. “Okay,” I say. “That’s helpful.” I turn away from him, the internal shield hardening as if my organs have been injected with concrete. I look to the open window beside his desk and think of how often over the last few years I fantasized about making a run for it, leaping out. I turn back to him. “I wonder if you’ll ever look back someday and consider that maybe, just maybe, I was telling the truth all along. I hope you do. I hope you wonder about that.”

His face is without emotion, cold and reptilian.

“Then again maybe you always knew my mother was lying, but what did you care, she was paying the bills, right?”

“I think you need to take a deep breath, Cassie,” he says, folding his arms across his chest. “You’re getting out of control.”

I can feel it in my stomach, the grenade he has just deposited in me. He watches now, waiting for it to explode so he can sit back, satisfied, and say, “See!”

I clamp my teeth down on the anger—just two more days here—

and turn back to the window, letting my mind drift beyond the glass, floating high into the treetops. All that’s left in this room is my body—my breath and my blood circulating at the energy-conserving level of a child’s night-light. The rest of me is gone. Dr. Meeks calls this dissociation.

I call it escape.

The truth is I have mixed feelings about leaving this place. I desperately want to go, but I have spent half of my teenage years here, insulated as an oyster and so far from the real world that I no longer know what it is or how to live in it. I feel like a newborn about to be dropped off on life’s doorstep, totally unequipped to navigate the world outside these doors. It’s no secret that Dr. Meeks thinks I’ll fail, that I’ll be back. Or worse, that I’ll be just another statistic. Another kid found too late, bleeding out in a bathtub or beside an empty bottle of pills.

Sometimes I worry that he’s right.

I wonder if it would feel different if I were going home. Not that I’ve been invited or that I think it would be a good idea, but the known universe always feels easier even when it’s miserable. Most of the kids here talk constantly about the glorious day when they will finally be reunited with their families, never mind the fact that it was their screwed-up parents who messed them up and then dumped them here. That’s another fact of life—it’s really hard not to love your parents, even when they suck. But I’m not like that. I try to have as little contact with my mother as possible. Every once in a while this primal longing erupts in me, a sort of lost-alone-in-the-dark desperation that strikes deep in my chest. But as soon as that happens, I hold my breath and suffocate the feeling until it

passes. I don’t want anything to do with her. Not after what she’s done.

But the thing is, when you don’t have a mother, you don’t have a home, and when you don’t have a home, there’s nowhere to go when you’re sad or scared or alone, even in your own mind, there’s just nowhere to go.

As if from a great distance, I hear Meeks ask me if I have anything I want to say to him before our final session is over.

“Actually,” I say, leaning forward, “there is one last, very important thing I want to tell you.”

He blinks and his head jerks back slightly in surprise. “Okay,” he says, summoning his best impression of a serious doctor—cupped hands, level brow, listening eyes. But his mouth betrays him, twisting as if to suppress the hope that he is finally about to get his breakthrough.

I take a deep breath. “I don’t know how to tell you this, but . . . I guess I’ll just go ahead and say it. Right now, at this very moment . . .” He leans in. “There are . . . little blue men climbing up the window behind you. They’re, oh my God, Dr. Meeks, I think they might be Smurfs!”

He leans back and sighs and rubs his temples. “Cassie,” he says.

“You’re not even going to look? You just want to believe that I’m crazy.”

I pretend to cry for a second, terrifically bad acting until he says, “Okay, Cassie, our session is over.”

“Free at last!” I jump happily to my feet.

He walks me to the door and then waves in his next patient.

It’s James, my best friend here and the only reason I have made it through this place with my sanity intact.

Just as Nurse Mary and I are leaving, I hear James scream, “Holy crap, Dr. Meeks! There are Smurfs climbing up your window!” and I laugh all the way back to the ward. It’s been almost two and a half years that James and I have been screwing with Meeks, and it never gets old for me.

Two and a half years, and now only two days left.

Instinctively, I look down at my wrists where the rope burns once were. Even though the years have passed so slowly, it’s still hard to believe it’s been that long since the day my parents dumped me here, since that terrible, terrible day.