The Formula for Murder (26 page)

Read The Formula for Murder Online

Authors: Carol McCleary

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Historical mystery

It occurred to Doyle that that was exactly how a detective should analyze a crime—looking for the minor, perhaps almost imperceptible differences in the evidence that lead from one suspect to another until the actual cause and perpetrator is found through a series of deductions, observations, and arriving at conclusions.

Viewing crime solving as a

science,

not just an art, was to be the formula he would use to create his detective.

He created a character named Sherrinford Holmes, then simplified the name to Sherlock and gave him a sidekick, Dr. Watson, to act as both a foil and a sparring partner for Holmes.

His first Sherlock Holmes book,

A Study in Scarlet,

was to be a major disappointment to him in many ways. First, presenting a manuscript to a publisher is a trying task for any writer. Manuscripts are handwritten, can run into hundreds of pages, and he had to laboriously copy by hand the entire manuscript for each publisher to which he submitted.

The reaction from publishers was also not elating. To find publishers rejecting his story after all the work and enthusiasm he put into writing it and the grim task of hand copying, was deflating to his ego and his aspirations.

Though he had been insulted by an offer of twenty-five pounds

17

from a publisher to purchase all rights to the story, with no further payment of royalties, he accepted the offer.

Publication was followed by such a lukewarm reception from readers, that he cast aside the Sherlock Holmes character, intending never to write another book about the detective who solved cases with scientific deductive reasoning.

For four years he floundered, trying to get his medical practice in good order while he wrote other stories that publishers and readers found even less gripping than the Holmes book.

His writing career had undergone a dramatic change the previous year during a dinner at London’s Langham Hotel. That night he and Oscar Wilde, a poet and social wit who Doyle had never met before, and who himself had never had a novel previously published, were both offered surprisingly respectable publishing arrangements by an American publisher of magazines who desired to publish the novels in weekly installments.

The reason he received an offer from an American publisher was that his Holmes novel had proved more popular in the United States than in Britain. And the offer, while modest for the amount of work it would take to create the story, was much fairer than the previous one.

18

Even better, the short novel he produced,

The Sign of the Four,

was a significant hit in both Europe and America, leading to publishing agreements for more Sherlock Holmes stories.

C

ONAN

D

OYLE

At thirty-one years and just beginning to have the success for which he had strived for years, he felt old. And still dissatisfied with his medical practice.

It was probably the slow, passive nature of his family-oriented practice that kept him from fully loving the profession he had studied so hard to obtain.

Thinking about the cryptic message he had received, he decided the visitors would provide an intriguing interlude for what had been a rather dull afternoon. While he was on holiday from his medical practice, he did have an occasional request for his medical services in Buckfastleigh from acquaintances.

Death and the black beast had to enliven a day in which the most exciting moment had been an elderly patient telling him that he had finally unplugged this morning after eating a large number of prunes.

44

No police are waiting for us at Buckfastleigh. Neither is a taxi.

We are told a taxi only comes to the station when it has been requested in advance. Buckfastleigh is a small town, a market town larger than Linleigh-on-the-moors, but still too small to host many city amenities.

We get instructions for Old Bridge House where Conan Doyle is staying. Since it is only a half mile walk, not terribly far since neither of us has a large piece of luggage, though Wells’s is more than twice the size of my valise, we set out on foot instead of by taxi.

“Wells, I hate to admit it, but my limited knowledge about Conan Doyle is from what Oscar told me—that his first name is Arthur, but he prefers to be called Conan. And I have a confession to make.”

“Really … this should be interesting.”

“I haven’t read any of Mr. Doyle’s books.”

“But you said—”

“A little white lie. I, uh, glanced at it in a bookstore. I meant to read it someday.”

“What is the purpose of this confession?”

“I was just thinking that, since you’ve read his detective stories, you’d be so kind as to tell me the plots so I could be courteous and pretend I had read them.”

To my surprise he refuses. “That’s not polite. It’s a fraud. Besides, it’s very easy to get tripped up.”

“I’ve done it many times and never had a problem.”

“Why don’t you just read the books?”

“Because,

Mr.

Wells,” I say tartly, “I am

quite

too busy climbing mountains, crossing rivers, and storming castles to have my head constantly stuck in a book. As I have pointed out to help you improve your opportunities in life, you spend too much time reading instead of doing.”

“You are absolutely right,

Miss

Bly. In fact, I have been counting my blessings since you brought action rather than just words into my life. To date, I am wanted by the police, stalked by a killer, and in the hands of a woman who was committed to a madhouse after being examined by three psychiatrists. One has to wonder how you managed to pull off being hopelessly insane so well. I’m sure you’ve heard that expression—where there’s smoke, there’s fire.”

19

So he knows about my insanity caper. I shut my mouth and grit my teeth. Sometimes the man is insufferable.

On occasion I have also found Wells mulish with his attitudes and I drop the subject knowing we will just end up in petty squabbling. While I admire his fine mind, cold logic and reason can be the enemy of invention.

* * *

O

LD

B

RIDGE

H

OUSE

sits next to a narrow stone bridge that looks ancient enough to have been used by Celtic farmers to herd sheep across and then by Roman legions marching to conquest. In the distance upriver there is a modern railroad span of steel girders that time and man will turn into a pile of rusty dust while the stone edifice built by hand will still be feeling the foot and wheels of mankind.

I would feel quite at home in the house next to the bridge. If houses have a spirit, I would say this one was a tranquil old soul.

“What a charming house,” I tell Wells. It’s another moor-stone granite, but larger than any we saw in Linleigh-on-the-moors, with four chimneys, and a large stone archway over the entrance to the property big enough for a carriage to pass through. Thatch, moss, and clinging vines cover the roof and top of the arch.

The bell at the front door reminds me of the one we had at the house my dad built for my mother—smooth gray metal that appears almost liquid and a little handle that looks like a fish tail to ring the bell with.

“Miss Bly and Mr. Wells … welcome.” Conan Doyle greets us after I clang the bell. “Please, come in.”

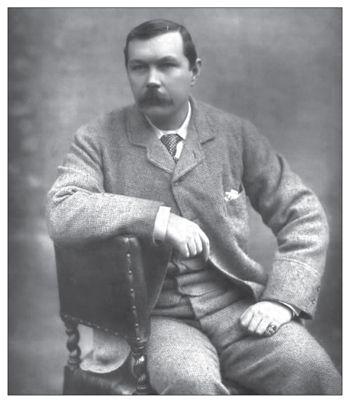

My instant impression of the author is that he appears to be in the medical professional he is—or even a counterjumper, I think, because Dr. Doyle looks a bit like H. G. Wells, with a similar thick, dark mustache, though he is a larger man.

The house and its furnishings are old and venerable, as seems Conan Doyle. Though Wells told me earlier that the man is only in his early thirties and while his features are that of a young man, he impresses me as an old soul as he observes me with a grave expression and large, gray eyes that radiate intelligent curiosity.

“I read about your exploits when you passed through London on your race,” Dr. Doyle says to me. “I was less amazed at your accomplishment in timing transportation than the raw courage it took to travel around the world when there is danger everywhere. Oscar told me that you even refused to carry the pistol that a friend offered.”

“The problem with relying upon guns is that it encourages others to get bigger ones or more of them to fight you with. Thank you for the compliment, but I must say the honor of our meeting is all mine, Dr. Doyle. I so love your Sherlock Holmes stories.”

“Thank you. Which one did you find most entertaining?”

“Oh…” I chirp and gesture to Wells as I am sinking beyond despair.

Why didn’t I read the books?

“All of them.”

“She enjoyed both

A Study in Scarlet

and

The Sign of the Four,

” Wells says, “as did I. I’ve written a few modest scientific articles, but hope someday to break into writing fiction.”

“A word of advice: Write because you desire to, not for the money or fame—that may take longer than you think or never come. Now shall we go into the parlor?”

Wells gives me an “I told you so” glare as Dr. Doyle leads us to the parlor.

We settle into some charming overstuffed chairs and partake of tea and cake while we chat.

“I don’t want to discourage you from writing fiction,” Dr. Doyle tells Wells, “that isn’t my intent. But it can be, as it was for me, a bumpy, depressing road before even modest success. Taking up the pen can be like taking a wolf by the ear.

“Miss Bly…” Mr. Doyle looks me.

“Yes?” I silently cross my fingers hoping he won’t ask me something specific about his books.

“Please, tell me what pitfalls you must encounter reporting crime stories, especially being a woman, which I’m very impressed by. Oscar is right when he said you are one of a kind.”

“Thank you.” For a moment I look down at my napkin. I’m really not used to compliments, especially from men. “The biggest difficulty is getting the newspaper to believe a woman is capable of such a task. They believe a woman’s place is in the home.” I give him a brief rundown of wrongs I have exposed, from the miserable conditions at a madhouse to the treatment of domestics and the terrible life prostitutes endure.

I get chuckles when I share with them Jules Verne’s agitation over the refusal of the French Academy to make him a member because they prefer what he calls “comedies of manners” over his bestselling adventure stories.

Very quickly the small talk and “war stories” are over and we face the task of explaining why I have journeyed several thousand miles and teamed up with Wells. I’m not sure how Wells feels about me giving the writer a rather whitewashed version of events, but from the way he is looking down at the floor a jury would easily peg him as guilt stricken.

The most significant details I omitted are the interest that New York police have in Hailey’s handling of the New York murder case, because I didn’t want to take away any sympathy Dr. Doyle would have for her, and that Wells and I are presently sought for questioning by the British police.

The fact we are probably on a wanted list would most likely get us escorted to the nearest constable by the respectable doctor-writer.

Dr. Doyle shows keen interest in the conversation I overheard regarding the child, Emma, at the spa. He stops me from going further with my tale and asks me to repeat everything I know about Emma and her prostitute mother, scoffing when I say the child died suddenly of “brain fever.”

“The deuce you say!” Dr. Doyle rubs his jaw. “Brain fever. What bunk! The use of a child at the spa for any purpose is completely outrageous. The authorities in Bath are obviously overlooking the situation because the spa attracts a wealthy and influential clientele. And you, H. G., in dealing with Dr. Lacroix you’ve never heard of children being used in his experiments?”

“No, children were not experimented upon, as far as I know, nor did I hear anything about children in regard to his university difficulties. But I only did research for him for a short time, so he may have had children involved at some point and I just wasn’t privy to the experiments.”

“I’m not familiar with Dr. Lacroix,” Dr. Doyle says, “though I’ve heard of the spa. Does he strike you as even capable of doing experiments that could harm a child?” His question is directed to Wells.

Wells chews on it for a moment. “I don’t find Lacroix to be an evil person in the sense that anyone would look upon him as capable of doing deliberate harm or acts of a criminal nature. I find it difficult to believe that he would

intentionally

harm a child. However, there is no question he becomes quite fanatical in terms of his medical research. I have no direct evidence to support this, just my impression from observing him, but I strongly suspect that he could consider experiments on a child that he believes are being done for the greater good of mankind, no different than experimenting on an adult or even an animal.”