The Four Walls of My Freedom (18 page)

Read The Four Walls of My Freedom Online

Authors: Donna Thomson

The problem with this treatment is that it is irrevocable. It denies the potential for growth and change in the human body â an extreme act that may ease the burden of care to families and state, but at a terrible human cost. There is no question that lifting, changing and bathing an adult is much more difficult than performing those tasks for a child. But a solution that is congruent with our most fundamental beliefs about dignity would not be the Ashley treatment. Rather, I believe that we should offer parents of severely disabled children a placement at the age of fifteen. If the parents choose to keep their child at home, they should be entitled to the equivalent care costs to be used in the family home. Currently, placements are virtually nonexistent for those with severe disabilities who are not wards of the state. Most families struggle on quietly until their son or daughter turns eighteen at which point the relatively “rich” children's services become a thing of the past. Society hasn't woken up to the fact that this generation of children with severe disabilities raised in family homes are surviving into adulthood. Those with conditions such as Down syndrome were expected to expire in early adulthood only twenty years ago. Today, their life expectancy is within a normal range if there are no medical complications. In the parent groups that Jim and I frequent, the eighteenth birthday of your child is called “falling off the cliff.” Some schools will keep teens with disabilities until the age of twenty-one, but after that there are often long waitlists for day programs, and a young adult is relegated to sitting at home watching television. Most parents have to give up work at this point to assume full-time caring responsibilities when their contemporaries are at their professional peak or planning an early retirement.

For parents in this position, housing solutions are often the most pressing need. Most want some kind of a home with the proper supports for their son or daughter, perhaps shared with a couple of other individuals who have similar care needs. Access to tax-sheltered savings such as the Disability Savings Plan combined with long-term-care funds released to the individual could go a long way to achieving this dream of “independent living.” Innovative and flexible legal frameworks could give incentive to parents who wish to create a social enterprise in housing provision for their loved one. A house is purchased, refurbished with specialized features, rented out to residents with care costs rolled in and a small board of directors manages the household staff and payroll. Profits from rental fees go to repaying investors and paying for building improvements. Members of personal support networks represent residents on the board (if residents cannot represent themselves) and ensure quality control of all services. Residents use a combination of state long-term-care funds and personal savings (such as the

RDSP

) to pay for care and housing. All social aspects of daily living are arranged by residents or members of their personal support networks.

Seniors could use some aspects of this model. Most people at retirement age have some savings in a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP). I would propose that any funds redeemed from that plan and used to pay for care should not be taxed whatsoever. This would entail providing receipts for care received and submitting them with an income tax return. Any monies spent on care would be eligible for a 100 percent tax refund. Governments cannot have their cake and eat it too. Societies cannot euthanize all its citizens who are too old, ill or disabled to be productive and parents should not be allowed to surgically ensure their children never grow up. A new deal that incentivizes saving and allows private investment into businesses that demonstrate a social purpose is a way forward that offers some hope for a good life. Amartya Sen recognizes disability as a central challenge to justice. “Given what can be achieved through intelligent and humane intervention, it is amazing how inactive and smug most societies are about the prevalence of the unshared burden of disability. In feeding this inaction, conceptual conservatism plays a significant role. In particular, the concentration on income distribution as the principal guide to distributional fairness prevents an understanding of the predicament of disability and its moral and political implications for social analysis.”

45

I want a good life for my son and my elderly mother. But I also want a good life for myself. Some of the challenges that I have described in my family could be addressed by an injection of cash. But a life that we value and have reason to value is one that has at its heart caring and belonging. If life is a piechart, money is only one slice. The care of vulnerable citizens is a corporate act on the part of society; it's not just the job of social workers. It takes a village to raise a child, but it takes every citizen in every village to help sustain each other.

I have never met another parent of a son or daughter with disabilities who did not know what they needed to thrive. We know that paid care, together with the love and support of friends, family and neighbours, is for us the key to a good life. This is a future we must build for everyone, including those with differing abilities. For the sake of love and decency, we must be allowed to build it.

In the course of this book moving from idea to the printed page there have been many people who generously offered their expertise and encouragement.

First among equals is Dr. Susan Hodgett who introduced me to the Capability Approach and subsequently offered research materials as well as an “advice line” that was always open, and always helpful. Everyone from the Cambridge University Capability Network generously provided me with an idea bank, and special thanks go to Dr. Cristina Devecchi and Dr. Michael Watts.

Professor Amartya Sen could not have been more delightful company, or more generous in his support of my work. I will always be a great admirer of him, both personally and professionally. His introduction to Dr. Sabina Alkire offered me a new avenue of exploration that proved fascinating. I have Dr. Alkire to thank for enriching this book, through her assistance with Chapter 16, “Being Well,” and enriching my home life through her wellbeing index for our family.

When I complained to Dr. Lorella Terzi that I had trouble holding on to complicated lines of reasoning in moral philosophy, she suggested that I go back to my sources and continue reading â a piece of advice that helped me to remain positive and hopeful, even when I felt out of my depth.

Eva Kittay and Al Etmanski were both early readers of the manuscript and their wise, critical comments challenged me to present my ideas in a more complex and truthful way.

To sustain my optimism, confidence and positive outlook, I have my women friends in London to thank (the “sisterhood”): Diana Saghi, Nora Lankes, Annie Maccoby, Beena Menon, Anita Ensor and Christine Fisher.

A very special debt of gratitude must be paid to my new publisher, Sarah MacLachlan at House of Anansi Press who gave my book its second life. Thanks also to Kim McArthur who initially published this book in 2010.

Without the loving support of our extended family, this book could never have been written. For their love and practical help, special thanks goes to Marjorie Higginson, the late Jean Wright, Karen Thomson and Frank Opolko, Cathie and Jerry Beauchamp and Rob and Carol Wright.

Finally, I am so grateful to have Jim, Nicholas and Natalie by my side. They fill my heart with love and optimism every day.

The Wright/Thomson Family Wellbeing Index: An Analysis

The author of the index to determine the wellbeing of our family is Dr. Sabina Alkire. Together with her colleague, James Foster, Dr. Alkire created the Gross National Happiness Index for the Kingdom of Bhutan (available at www.grossnationalhappiness.com/gnhIndex/intruduction

GNH

.aspx). The same “union” approach as is used in the Bhutanese index was used to analyze the results of our index â that is, all deprivations are counted from zero (rather than allowing some baseline of shortfalls from sufficiency to be present for everyone and yet they could still be evaluated as being entirely happy). We used the scale of 0â5, with 5 representing perfect happiness, or wellbeing. At the top end of the scale, Dr. Alkire and I agreed that a score of 4 was a reasonable “sufficiency cut-off” to be labelled as happy.

Anyone can replicate this survey. The essential thing is to choose three time periods and discuss with all the subjects the main events that shaped the family experience. Ensure that everyone agrees on definitions for the domains under consideration. Sabina Alkire suggested that I attempt to predict scores for my family members, which proved a fascinating and illuminating experience.

Overview

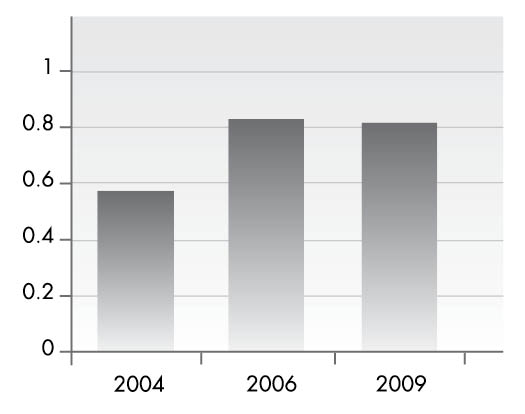

If happiness is “1” and unhappiness is “0,” then each person and each indicator is weighted equally over time, this is what we see:

Individually Over Time

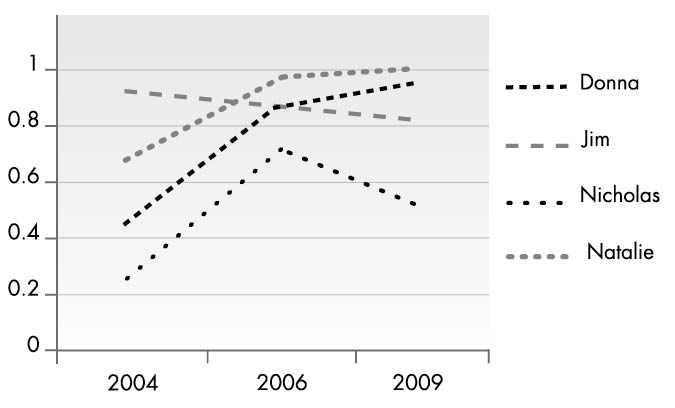

Seen individually over time, here is a line graph representation of how we assessed our own wellbeing in 2004, 2006 and 2009.

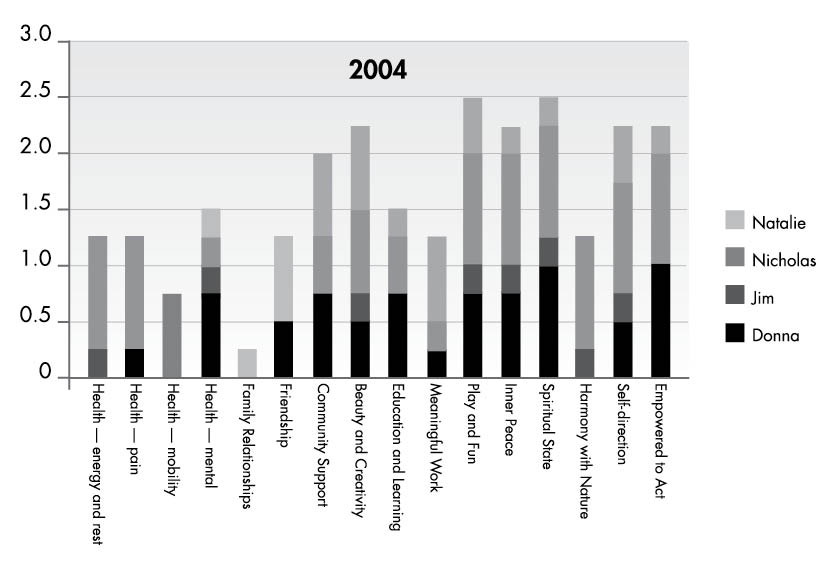

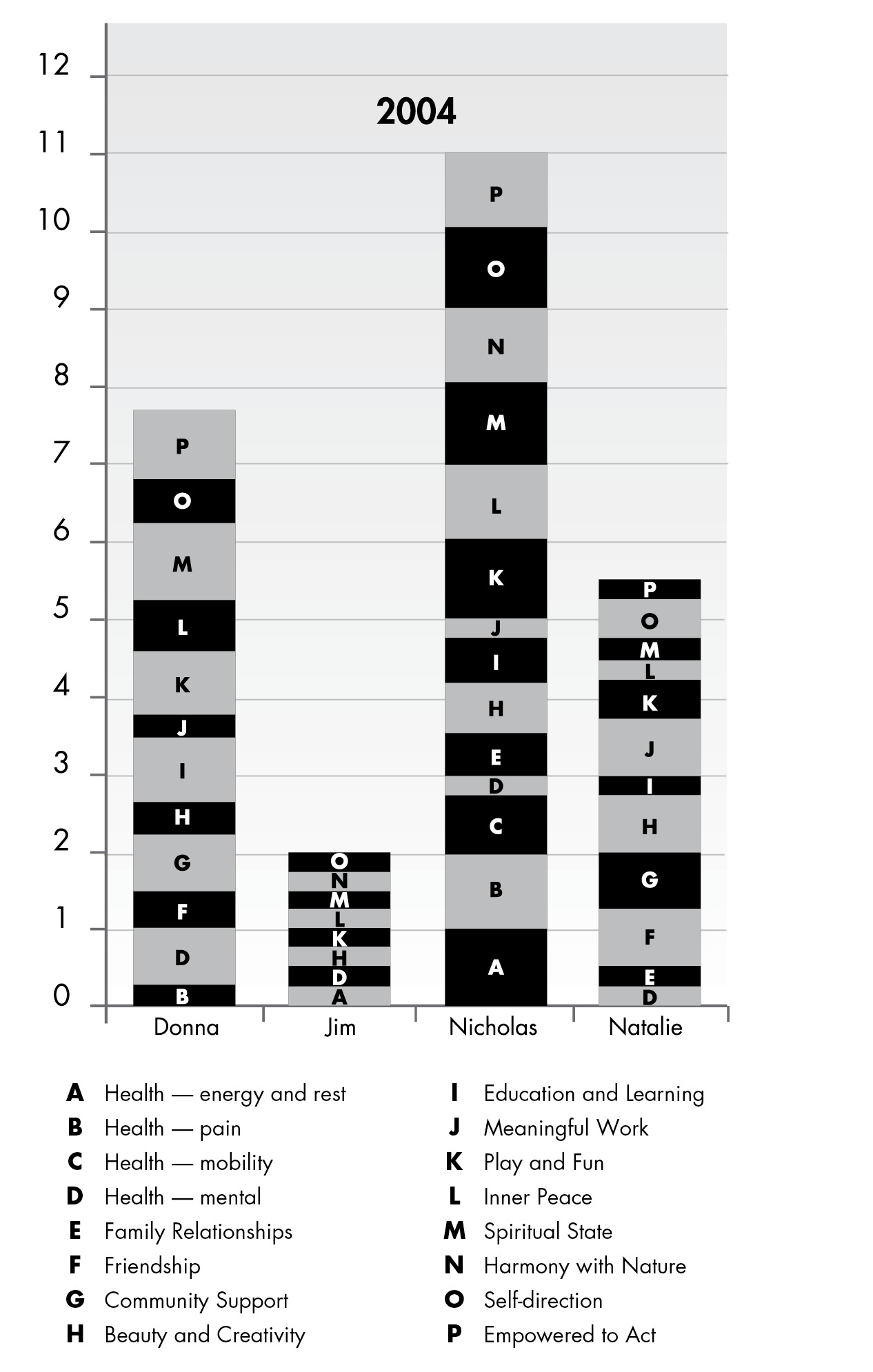

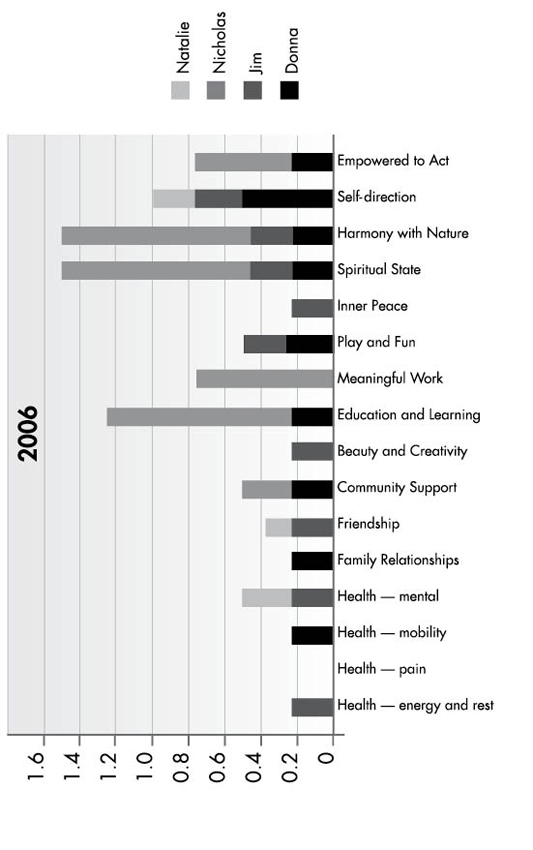

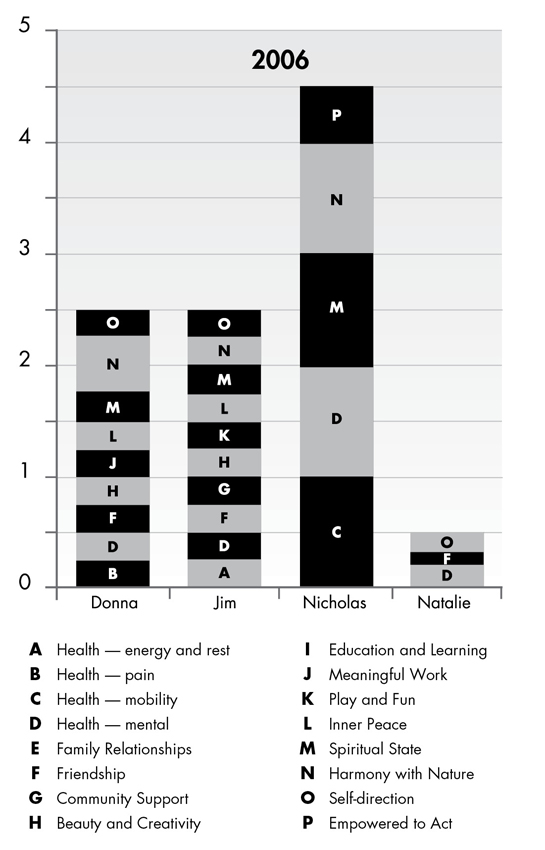

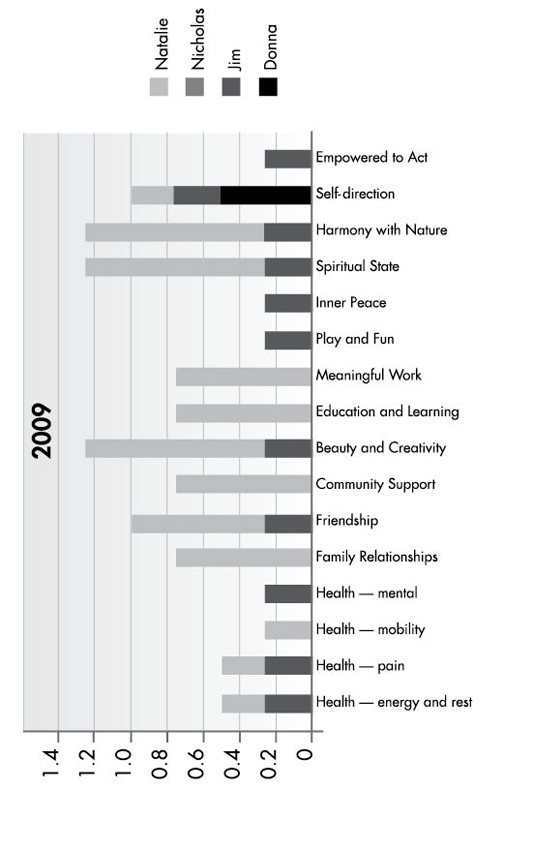

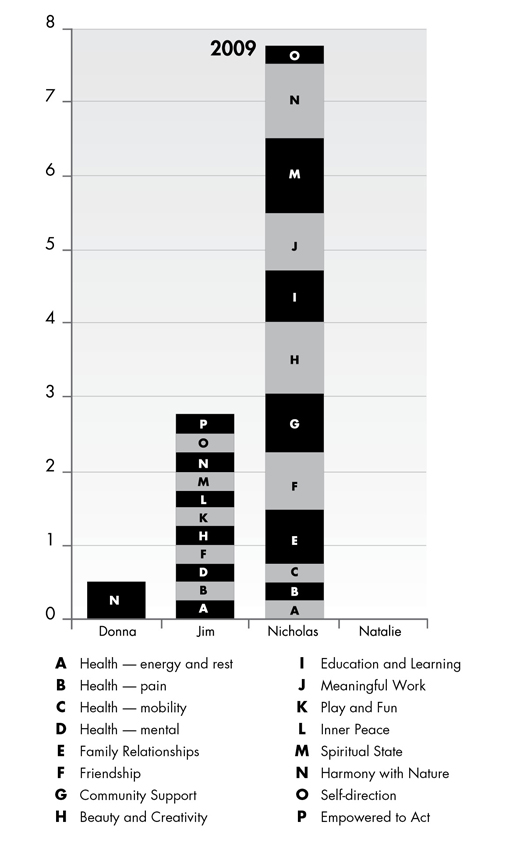

Looking more closely at individual results offers a deeper understanding of how we felt about the events of our lives in 2004, 2006 and 2009. The bar graphs that follow represent how much “unhappiness” was experienced by each family member in each domain that year.

In 2004, Nicholas and I had the highest proportions of unhappiness. Natalie had relatively high levels of unhappiness in the areas of friendship, community support, beauty and creativity and meaningful work. Her health was excellent, though, and she felt in harmony with nature. Jim experienced low levels of unhappiness in all domains.

Here, we see the unhappiness experienced by each member of the family in 2004. Clearly, Nicholas and Donna were the most unhappy family members, but we are able to see the source of their unhappiness.

The year 2006 sees an overall improvement in the wellbeing of the family, but Nicholas is still somewhat unhappy, especially in the areas of education, harmony with nature and meaningful work. I suspect that his high unhappiness score in the area of spiritual state reflects his ambivalence about the domain itself. Natalie is very happy and Donna has improved significantly in all areas. Interestingly, Jim is less happy in 2006 than he was in 2004. During our conversations, he reported higher unhappiness scores in the areas of harmony with nature and general health and wellbeing due to the stress of a new job.

And note the differences in 2009.

Natalie has scored a “4” or “5” in each domain, so she is considered perfectly “happy.”

As for Nicholas, it is interesting that he rates his health scores as fairly well. This is in spite of the fact that since 2006, he has become progressively more bedridden. Staying in bed gives Nick pain relief, but it causes him to be less satisfied in other areas of his life, such as self-direction, harmony with nature, beauty and creativity and meaningful work. Jim reported that although he loves life in London, he misses the extended family, weekends at the cottage and harmony with nature. Shortfalls in those areas cause his scores to reflect a slightly higher level of unhappiness than in 2004.