The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (4 page)

Read The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople Online

Authors: Jonathan Phillips

Tags: #Religion, #History

The death of Manuel Comnenus meant that the Frankish settlers could no longer hope for help from the Greeks, and their efforts to secure support from Europe were hardly more successful. England and France were locked in decades of acrimonious feuding and skirmishing and, in spite of the impassioned pleas of Frankish envoys, their kings were unwilling to settle their differences to help defend the Holy Land and offered only financial assistance.

In the kingdom of Jerusalem the reign of the leper-king, Baldwin IV (1174—85), weakened the Franks further because his slow and terrible decline encouraged plotting and feuding amongst those trying to succeed him.

23

In spite of these problems, the settlers’ military prowess held off Saladin until 1187 when the pendulum swung firmly in favour of the sultan. He crushed the Christians at the Battle of Hattin and soon captured Jerusalem to leave the Franks with barely a fingerhold on the coast. Now, belatedly, western Europe had to act.

23

In spite of these problems, the settlers’ military prowess held off Saladin until 1187 when the pendulum swung firmly in favour of the sultan. He crushed the Christians at the Battle of Hattin and soon captured Jerusalem to leave the Franks with barely a fingerhold on the coast. Now, belatedly, western Europe had to act.

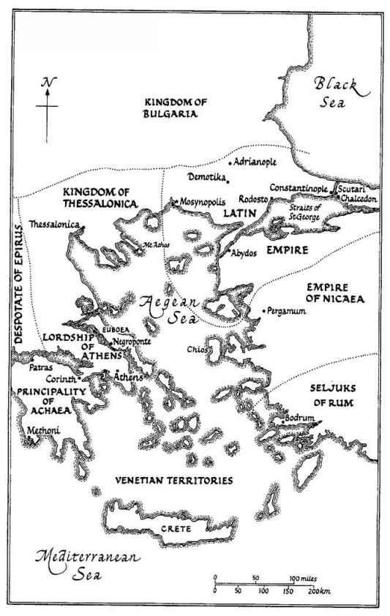

The Latin Empire and its neighbours c.1214

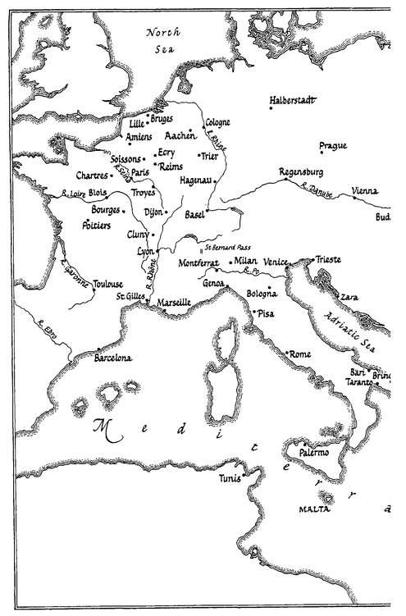

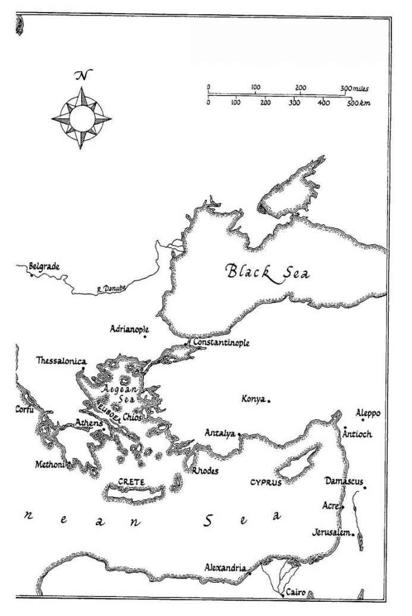

Europe and the Near East

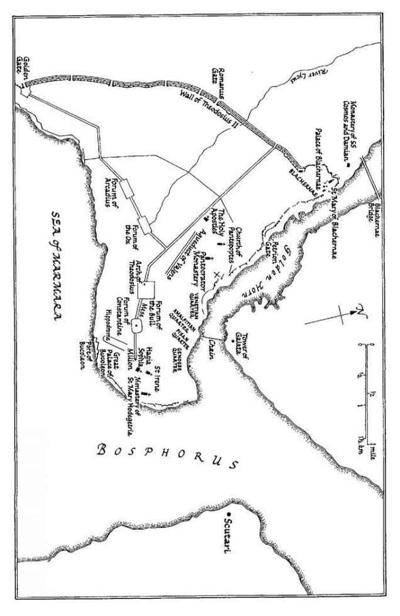

Constantinople, 1203-4

CHAPTER ONE

‘Oh God, the Heathens are come into thine inheritance’

The Origins and Preaching of the Fourth Crusade, 1187—99)On hearing with what severe and terrible judgement the land of Jerusalem has been smitten by the divine hand ... we could not decide easily what to do or say: the psalmist laments: ‘Oh God, the heathens are come into thine inheritance.’ Saladin’s army came on those regions ... our side was overpowered, the Lord’s Cross was taken, the king was captured and almost everyone else was either killed by the sword or seized by hostile hands ... The bishops, and the Templars and Hospitallers were beheaded in Saladin’s sight ... those savage barbarians thirsted after Christian blood and used all their force to profane the holy places and banish the worship of God from the land. What a great cause for mourning this ought to be for us and the whole Christian people!

1

With these powerful and anguished words, Pope Gregory VIII lamented the defeat of the Christian army at the Battle of Hattin on 4 July 1187. Within three months of his victory the great Muslim leader, Saladin, had swept through the Frankish lands and achieved the climax of his

jihad,

with the capture of Jerusalem.

jihad,

with the capture of Jerusalem.

The loss of Christ’s city provoked grief and outrage in Europe. The rulers of the West, temporarily at least, put aside their customary disharmony and in October 1187 the papacy launched the Third Crusade to recover the Holy Land. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany (1152—90), the most senior figure in Christendom, led a huge contingent of up to 100.000 men, but as he waded across a river in southern Asia Minor he suffered a fatal heart attack and died. The German force broke up and it was left to the armies of King Philip II Augustus of France (1180—1223) and Richard I of England (1189—99) to take the fight to the armies of Islam. In the West, these two men were bitter enemies and their relationship on the crusade hardly improved. In theory, Philip was Richard’s overlord, but in practice the English king’s energy and military skills meant that everyone recognised him as the dominant figure. The contemporary Muslim writer Beha ad-Din noted: ‘the news of his coming had a dread and frightening effect on the hearts of the Muslims ... He had much experience of fighting and was intrepid in battle, and yet he was, in their [the Franks’] eyes below the royal status of the king of France, although richer and more renowned for martial skill and courage.’

2

2

The two kings arrived in the Levant during the early summer of 1191. Philip soon departed to deal with urgent political matters in northern France, but Richard remained in the East for another 18 months. His victories in battles at Arsuf and Jaffa did much to undermine Saladin’s reputation, but the crusaders were unable to make a serious attempt to retake Jerusalem itself. Richard did, however, do much to re-establish the Crusader States along the coastline (stretching from northern Syria to Jaffa in modern Israel) and to restore them as a viable political and economic entity. News of intrigues between Philip and Prince John eventually forced him to leave the eastern Mediterranean, but, as he sailed, a contemporary English crusader quoted him as saying: ‘O Holy Land I commend you to God. In his loving grace may He grant me such length of life that I may bring you help as He wills. I certainly hope some time in the future to bring you the aid that I intend.’

3

3

Richard had gained a heroic reputation, but during his journey home he was captured by political rivals and spent 15 months in prison at the hands of the duke of Austria and then the emperor of Germany. King Philip exploited his absence to take large areas of Richard’s territories in northern France, which meant that once the English ruler was free, he was much preoccupied with re-establishing his authority. In these circumstances Richard could do little, in the mid-1190s, to fulfil his promise to help the Holy Land.

4

4

Richard’s departure could have been disastrous for the Franks in the Levant, but to their great good fortune, just six months after the king sailed, Saladin died, worn out by decades of warfare. The unity of the Muslims in the Middle East was shattered and a series of factions emerged in Aleppo, Damascus and Cairo, each more concerned to form alliances to defeat the other than with fighting the Franks. The Christians were able to continue their recovery and Frederick Barbarossa’s son, Emperor Henry VI (1190—7), hoping to fulfil his father’s vows, launched a new crusade (known to historians as the German Crusade). This seemed to offer a real opportunity to exploit the Muslims’ disharmony, yet once again the Franks’ hopes were to be dashed. In the early winter of 1197 came news that the emperor had died of a fever at Messina in southern Italy. The German forces returned home and, with Henry’s son Frederick aged only two, the empire was thrown into a civil war between rival claimants for the imperial title. Pope Celestine III—by this time well into his nineties—tried to mediate, but with little success.

On 8 January 1198 Celestine died, and later that same day the cardinal-bishops and bishops of the Catholic Church in Rome made an inspired choice as his replacement. They elected Lothario of Segni as Pope Innocent III, the man who would become the most powerful, dynamic and revered pontiff of the medieval period. Innocent provided the vision and drive that the papacy had lacked for generations. His pontificate saw crusades against Muslims in Spain and the Holy Land, against heretics, renegade Catholics, Orthodox Christians, as well as the pagan people of the Baltic. He permitted the foundation of the Franciscan and Dominican friars; excommunicated kings and princes; and revitalised the administration of the papal court, enabling the authority of Rome to reach ever more widely across Catholic Europe.

5

5

Elected pope at the age of 37, Innocent was one of the youngest men ever to ascend the throne of St Peter. He was born in 1160 or 1161 into a landowning family at Segni, about 30 miles south-east of Rome, and his early education was at the Benedictine abbey of St Andrea al Celio in Rome itself. In the early 1180s he travelled north to Paris University: the intellectual hub of medieval Europe and the most admired centre of theological study. Here Innocent received the best education available in his age and formed many of the spiritual and philosophical ideas that would shape his conception of the papacy. He bolstered this theological background with a legal training and for three years (1186-9) studied at the law school of Bologna—again the most prestigious institution of its sort in the West. Around this time the papacy became increasingly legalistic in its procedures, and Innocent’s intellectual capabilities, allied with his deep spirituality and personal presence, were perfectly tailored to the needs of the Curia.

6

6

Written sources indicate that the pope was of average height and good-looking. A mosaic portrait from about 1200 is the most contemporaneous image that we have and it shows a man with large eyes, a longish nose and a moustache. A fresco from the church of San Speco, Subiaco, depicts him in full papal dignity, complete with the ceremonial mitre, pallium (a length of material draped around the neck that symbolised high ecclesiastical office) and mantle (see plate section). Innocent was known for his skills as a writer and as a persuasive public speaker: his ability to compose and deliver sermons was exceptional. He had a sharp sense of humour, too: the envoy of one of his most bitter political opponents sought an audience and was greeted with the comment: ‘Even the devil would have to be given a hearing—if he could repent.’

7

7

A great corpus of papal letters provides some insight into Innocent’s mind. Over-familiar as we are today with endless layers of paperwork, one might expect the papacy to have been a cradle of bureaucratic complexity, but prior to the thirteenth century this was not always so While earlier popes had preserved copies of some important documents, it was not until the time of Innocent III that a systematic archive was kept. Of the thousands of letters sent out from, and received by, the papal secretariat, the most significant were copied into specially bound volumes (known as registers), arranged by pontifical year, dating from the date of coronation (not election), which in Innocent’s case was 22 February. It is true that some of these letters were redrafted before being placed in the register; that many were probably written by secretaries, rather than the pope himself; and that much of year three and all of year four of the record (1200—2) have been lost. Nonetheless, it remains an invaluable body of material, which enables us to follow Innocent’s planning of the crusade and his reactions to its progress.

8

8

Other books

Emperor of a Dead World by Kevin Butler

The Wolf You Feed Arc by Angela Stevens

Better Together by Sheila O'Flanagan

Escape to Eden by Rachel McClellan

The Circus Fire by Stewart O'Nan

The Gypsy Crown by Kate Forsyth

Five Wicked Kisses - A Tasty Regency Tidbit by Anthea Lawson

Lucky Like Us: Book Two: The Hunted Series by Jennifer Ryan

Cafe Romance by Curtis Bennett

Discworld 26 - The Thief of Time by Pratchett, Terry