The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (57 page)

Read The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople Online

Authors: Jonathan Phillips

Tags: #Religion, #History

The crusader army was not, however, a faultless military machine—witness the temporary loss of formation outside the Theodosian walls in June 1203 and Louis of Blois’s reckless charge at Adrianople in 1205, both ironically caused by a chivalric desire for glory. Nevertheless, they formed a truly formidable fighting force.

The horsemanship of the knights was complemented by the unparalleled seafaring capabilities of the Venetians. Centuries of maritime experience meant that the Italians were amongst the elite of medieval sailors. The Venetian shipyards had more than a year to prepare for the campaign and their vessels and equipment were in excellent condition. The huge fleet sailed from the Adriatic to Constantinople with barely any losses and then, in the heat of battle, the Venetians proved themselves fully committed and courageous. The amphibious landing at Galata and the fabrication of the extraordinary siege machinery at the top of their vessels in June 1203 and April 1204 showed their improvisational skills, while bringing and holding their ships to the shore to deliver these attacks demonstrated their remarkable prowess as mariners. The quality of the Venetian fleet and its contribution to the crusade’s success dramatically highlighted the decline of the Byzantine navy.

Finally, again in contrast to the Greeks, the crusaders had effective commanders. The leadership was a mix of younger men, such as Baldwin of Flanders and Louis of Blois, and more experienced warriors. In July 1203 Hugh of Saint-Pol wrote to a friend in the West who had expressed concern about some of the knights: ‘you were exceedingly upset because I had undertaken the pilgrimage journey with such men who were young in age and maturity and did not know how to render advice in such an arduous affair’.

10

As time went on, however, this worry must have faded as everyone became battle-hardened. Generally, Baldwin of Flanders, Boniface of Montferrat, Louis of Blois, Hugh of Saint-Pol, Conan of Béthune and Geoffrey of Villehardouin, along with Doge Dandolo, worked in close harmony. Their determination to keep the campaign moving impelled the crusade onwards and ensured that it did not completely fragment. This broad co-operation also represented a stark contrast to the destructive bickering and tension that marked earlier expeditions, particularly the relationship between Richard the Lionheart and Philip of France during the Third Crusade.

10

As time went on, however, this worry must have faded as everyone became battle-hardened. Generally, Baldwin of Flanders, Boniface of Montferrat, Louis of Blois, Hugh of Saint-Pol, Conan of Béthune and Geoffrey of Villehardouin, along with Doge Dandolo, worked in close harmony. Their determination to keep the campaign moving impelled the crusade onwards and ensured that it did not completely fragment. This broad co-operation also represented a stark contrast to the destructive bickering and tension that marked earlier expeditions, particularly the relationship between Richard the Lionheart and Philip of France during the Third Crusade.

Throughout the crusade Enrico Dandolo proved a monumentally influential figure—an unrivalled source of advice and encouragement for the other leaders. His demand to be thrust to the forefront during the assault on the walls of the Golden Horn in July 1203 was a moment of genuine inspiration and appealed perfectly to the crusaders’ sense of honour and mutual competitiveness. Baldwin of Flanders too emerged as a man of sufficient standing and integrity to be the popular choice as the first Latin emperor of Constantinople.

While the martial qualities of the crusader warriors cannot be disputed, nothing can excuse the excesses perpetrated during the sack of Constantinople, although their behaviour can, perhaps, be explained. The combination of decades of ill-feeling between the Greeks and Latins, coupled with the tensions of months of conflict outside Constantinople, exploded in an appalling wave of violence and greed. Horrific events following sieges or battles were by no means new—witness the aftermath of the capture of Jerusalem in 1099. The western ‘barbarians’ were, however, not the sole perpetrators of such acts in the medieval world and this simple label should not obscure the fact that the Byzantine Empire’s institutionalised duplicity and considerable capacity for violence did not always give them a clear position on the moral high ground. The savagery of the Greeks towards the Europeans in Constantinople in 1182 was one example of this. Nor were atrocities the exclusive province of warfare in the eastern Mediterranean as the 1258 sack of Baghdad by the Mongols, and the Norman invaders’ terrible ravaging of northern England in 1068-9, demonstrate.

To the contemporary Byzantines, as much as modern commentators, it was the crusaders’ stated purpose as holy warriors that made the episode especially hard to understand. While an appreciation of the values of medieval society does much to illuminate events of the time, even Pope Innocent had to acknowledge that, with regard to the Fourth Crusade, at least, sometimes even he could not fathom the ways of God. The crusaders, elated at overcoming the most enormous odds, had no doubt that they had received a divine blessing. Once the expedition had ended and the longer-term problems of establishing and running an empire emerged, delight at the capture of Constantinople soon became a distant memory and this new Catholic outpost became a distraction from the relief of the Holy Land.

The legacy of the sack of Constantinople is most acute in the Greek Orthodox Church where a deep-rooted bitterness at the perceived betrayal of Christian fraternity has long lingered.

11

The full story behind the conquest is, as we have seen, more complicated than this allows. Even so, whether in its morality or its motivation, it remains one of the most controversial, compelling and remarkable episodes in medieval history.

11

The full story behind the conquest is, as we have seen, more complicated than this allows. Even so, whether in its morality or its motivation, it remains one of the most controversial, compelling and remarkable episodes in medieval history.

In the immediate aftermath of the conquest the troubadour Raimbaut of Vaqueiras, an eye-witness, acknowledged the crusaders’ misdemeanours and set out the task that faced them if they were, in their own terms at least, to make good their misdeeds:

For he [Baldwin] and we alike bear guilt for the burning of churches and the palaces, wherein I see both clerics and laymen sin; and if he does not succour the Holy Sepulchre and the conquest does not advance, then our guilt before God will be greater still, for the pardon will turn to sin. But if he be liberal and brave, he will lead his battalions to Babylonia and Cairo with the greatest ease.

12

By this time it was a challenge the crusaders could never hope to meet.

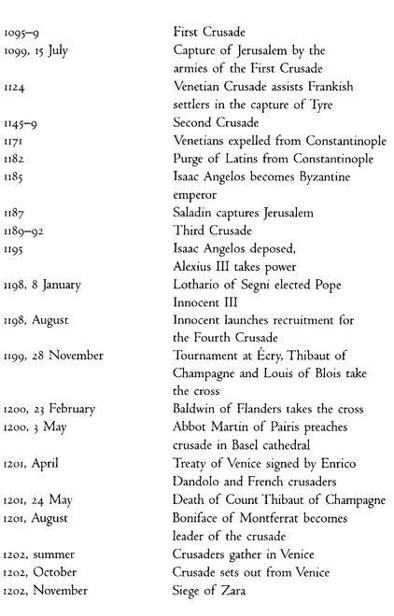

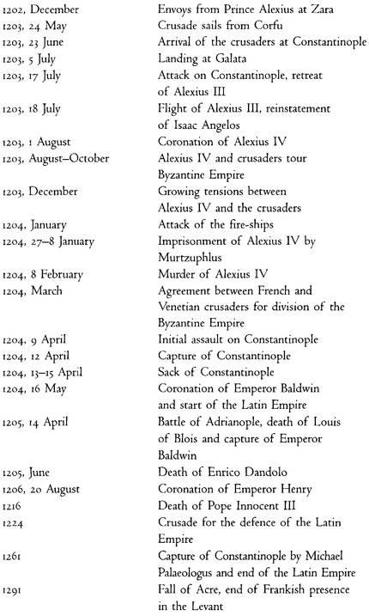

Chronology

Notes

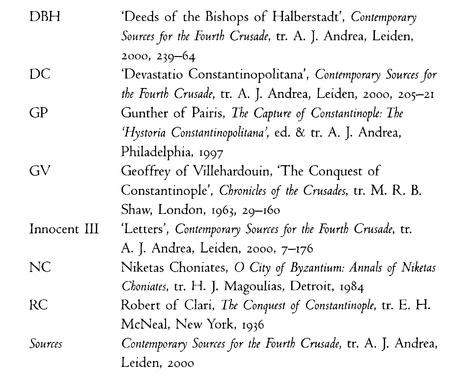

ABBREVIATIONS

1

NC, 314-15.

NC, 314-15.

2

The most detailed narrative of the expedition is by Queller and Madden,

Fourth Crusade,

whose perspective is as historians of Venice. Another good account of the campaign is Godfrey,

1204. The Unholy Crusade.

The most detailed narrative of the expedition is by Queller and Madden,

Fourth Crusade,

whose perspective is as historians of Venice. Another good account of the campaign is Godfrey,

1204. The Unholy Crusade.

3

Vehemently anti-western accounts of the crusade written by Byzantine historians include: Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III; Norwich,

Byzantium: The Decline and Fall,

156-213. For more balanced and scholarly views, see: Harris,

Byzantium and the Crusades;

Angold,

The Fourth Crusade.

Vehemently anti-western accounts of the crusade written by Byzantine historians include: Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III; Norwich,

Byzantium: The Decline and Fall,

156-213. For more balanced and scholarly views, see: Harris,

Byzantium and the Crusades;

Angold,

The Fourth Crusade.

4

Constable, ‘The Historiography of the Crusades’.

Constable, ‘The Historiography of the Crusades’.

5

Siberry, ‘Images of the Crusades in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’,

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades,

314.

Siberry, ‘Images of the Crusades in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’,

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades,

314.

6

Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III, 469, 480.

Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III, 469, 480.

7

Cited in Bartlett,

Medieval Panorama,

12-13.

Cited in Bartlett,

Medieval Panorama,

12-13.

8

Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III, 474.

Runciman,

History of the Crusades,

III, 474.

9

Riley-Smith, ‘Islam and the Crusades in History and Imagination’, 164-7.

Riley-Smith, ‘Islam and the Crusades in History and Imagination’, 164-7.

10

Phillips, ‘Why a Crusade will lead to a

jihad’.

Phillips, ‘Why a Crusade will lead to a

jihad’.

11

Innocent III,

Sources,

107.

Innocent III,

Sources,

107.

12

Innocent III,

Sources,

173—4.

Innocent III,

Sources,

173—4.

13

See especially the comments by Harris, ‘Distortion, Divine Providence and Genre in Niketas Choniates’ Account of the Collapse of Byzantium’.

See especially the comments by Harris, ‘Distortion, Divine Providence and Genre in Niketas Choniates’ Account of the Collapse of Byzantium’.

14

Jackson, ‘Christians, Barbarians and Masters: The European Discovery of the World Beyond Islam’.

Jackson, ‘Christians, Barbarians and Masters: The European Discovery of the World Beyond Islam’.

15

Bull, ‘Origins’.

Bull, ‘Origins’.

16

Guibert of Nogent, cited in and translated by Bull,

Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade,

3.

Guibert of Nogent, cited in and translated by Bull,

Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade,

3.

17

William of Tyre, I, 372—3.

William of Tyre, I, 372—3.

18

The best account of this is Hillenbrand,

The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives.

The best account of this is Hillenbrand,

The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives.

19

See Phillips and Hoch,

Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences,

1—14.

See Phillips and Hoch,

Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences,

1—14.

20

Harris,

Byzantium and the Crusades,

116—20.

Harris,

Byzantium and the Crusades,

116—20.

21

Eustathios of Thessaloniki,

The Capture of Thessaloniki,

35.

Eustathios of Thessaloniki,

The Capture of Thessaloniki,

35.

22

William of Tyre, II, 465.

William of Tyre, II, 465.

23

Hamilton,

The Leper King and His Heirs: King Baldwin IV and the Crusader States.

Hamilton,

The Leper King and His Heirs: King Baldwin IV and the Crusader States.

1

Gregory VIII,

Audita tremendi,

64—5.

Gregory VIII,

Audita tremendi,

64—5.

2

Beha ad-Din,

The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin,

146, 150.

Beha ad-Din,

The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin,

146, 150.

3

Chronicle of the Third Crusade,

382.

Chronicle of the Third Crusade,

382.

4

This period is expertly analysed by Gillingham,

Richard I,

155-301.

This period is expertly analysed by Gillingham,

Richard I,

155-301.

5

A good, modern biography of Innocent is: Sayers,

Innocent III.

Also important are the essays collected in: Innocent

III: Vicar of Christ or Lord of the World?,

ed. Powell; Pope Innocent

III

and his World, ed. Moore.

A good, modern biography of Innocent is: Sayers,

Innocent III.

Also important are the essays collected in: Innocent

III: Vicar of Christ or Lord of the World?,

ed. Powell; Pope Innocent

III

and his World, ed. Moore.

6

Sayers,

Innocent III,

10-27; Peters, ‘Lothario dei Conti di Segni becomes Pope Innocent III’, in:

Innocent III and his World,

3—24.

Sayers,

Innocent III,

10-27; Peters, ‘Lothario dei Conti di Segni becomes Pope Innocent III’, in:

Innocent III and his World,

3—24.

7

Sayers,

Innocent III,

2.

Sayers,

Innocent III,

2.

8

Innocent III,

Sources,

7—9.

Innocent III,

Sources,

7—9.

9

Innocent III,

Sources,

9, n.4.

Innocent III,

Sources,

9, n.4.

10

Ross,

Relations between the Latin East and the West, 1187—1291,

58—60.

Ross,

Relations between the Latin East and the West, 1187—1291,

58—60.

Other books

Keeping Secret: Secret McQueen, Book 4 by Sierra Dean

Betrayal by Robin Lee Hatcher

Creating Harmony by Viola Grace

Weekend Lover by Melissa Blue

Manhandled: A Rockstar Romantic Comedy (Hammered Book 2) by Cari Quinn, Taryn Elliott

A Disappearance in Damascus by Deborah Campbell

A Missing Peace by Beth Fred

Preserving Hope by Alex Albrinck

EXONERATION (INTERFERENCE) by Kimberly Schwartzmiller