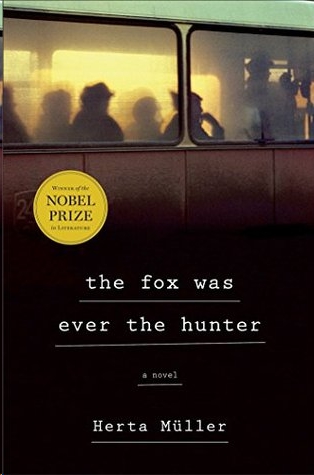

The Fox Was Ever the Hunter

Read The Fox Was Ever the Hunter Online

Authors: Herta Müller

Thank you for buying this

Henry Holt and Company ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click

here

.

That doesn’t matter, I said to myself.

Doesn’t matter at all.

—Venedikt Yerofeyev

The ant is carrying a dead fly three times its size. The ant can’t see the way ahead, it flips the fly around and crawls back. Adina doesn’t want to block the ant’s path so she pulls in her elbow. A clump of tar next to her knee glistens as it seethes in the sun. Adina dabs at the tar with her finger, raising a thin thread that stiffens in the air before it snaps.

The ant has the head of a pin, the sun can’t find any place to burn. The sun stings. The ant loses its way. It crawls but is not alive, the human eye does not consider it an animal. The spike heads of the grasses on the outskirts of town crawl the same way. The fly is alive because it’s three times the size of the ant and because it’s being carried, the human eye does consider the fly an animal.

Clara is blinded by the blazing pumpkin of the sun and doesn’t see the fly. She sits with her legs apart and rests her hands between her knees. Pubic hair shows where her swimsuit cuts into her thighs. Below her pubic hair is a pair of scissors, a spool of white thread, sunglasses and a thimble. Clara is sewing a summer blouse for herself. The needle dives, the thread advances, the needle pricks her finger and Clara licks the blood and spits out a shorthand curse involving ice and thread: your mother on the ice. A curse implying unspeakable things done to the mother of the needle. When Clara curses, everything has a mother.

The mother of the needle is the place that bleeds. The mother of the needle is the oldest needle in the world, the one that gave birth to all needles. The mother of the needle watches out for all her children, she is always looking for a finger to stab on every sewing hand in the world. The world contained in the curse is tiny, tucked under a cluster of needles and a clot of blood. And the mother of all thread is there too, lurking inside the curse, a massive tangle looming over the world.

All this heat and you’re going on about ice, says Adina, as Clara’s jawbones grind away while her tongue beats inside her mouth. Whenever she curses, Clara’s face wrinkles up, because every word is a well-aimed bullet fired from her lips and every word hits its mark. As well as the mother of its mark.

Clara lies down on the blanket next to Adina. Adina is naked, Clara is wearing her swimsuit bottom and nothing else.

* * *

Curses are cold. They have no need of dahlias or bread or apples or summer. Curses are not for smelling and not for eating. Only for churning up and laying down flat, for an instant of rage and a long time keeping still. Curses lower the throbbing of the temples into the wrist and hoist the dull heartbeat into the ear. Curses swell and choke on themselves.

Once a curse is lifted, it never existed.

* * *

The blanket is spread out on the roof of the apartment block, which is surrounded by poplars. The poplars rise higher than all the city roofs and are draped with green, they don’t show individual leaves, only a wash of foliage. They don’t swish, they whoosh. The foliage rises straight up on the poplars just like the branches, the wood cannot be seen. And where nothing else can reach, the poplars carve the hot air. The poplars are green knives.

* * *

When Adina stares at the poplars too long, they dig their knives inside her throat and twist them from side to side. Then her throat gets dizzy. And her forehead senses that no afternoon is capable of holding even a single poplar for the time the light takes to sink behind the factory into the evening. The evening ought to hurry, the night might succeed in holding the poplars, because then they can’t be seen.

* * *

The day is shattered by the beating of rugs between apartment blocks, the blows echo up to the roof and collapse one onto the other, the way Clara’s words do when she curses.

The beating of rugs cannot hoist the dull heartbeat into the ear.

* * *

Clara is tired after her curse, and the sky is so empty she closes her eyes, which are blinded by the light, while Adina opens her eyes wide and gazes far too long into the emptiness. From high overhead, beyond the reach even of the green knives, a taut thread of hot air stretches straight down to her eyes. And from this thread hangs the weight of the city.

* * *

That morning at school a child said to Adina, the sky looks so different today. A boy who’s always very still when he’s with the others. His eyes are set far apart, which makes his temples look narrow. My mother woke me up at four o’clock this morning, he said, and she gave me the key because she had to go to the train station. I walked out to the gate with her. When we were going through the courtyard the sky was so close I could feel it on my shoulder. I could have leaned back against it, but I didn’t want to scare my mother. When I went back by myself I could see right through all the stones. So I hurried as fast as I could. The door to our building looked different, the wood was empty. I could have slept another three hours, the child said, but I never fell back asleep. And even though I wasn’t sleeping I still woke up scared. Only maybe I really did sleep, because my eyes felt all pinched up. I had this dream that I was lying in the sun next to the water and I had this blister on my stomach. I pulled the skin off the blister but it didn’t hurt. Because under my skin was stone. Then the wind blew and lifted the water into the air, but it wasn’t water at all, just a wrinkled cloth. And there weren’t any stones underneath either, only flesh.

* * *

The boy laughed into that last sentence, and into the silence that followed. His teeth were like gravel, the blackened half teeth and the smooth white ones. The age in his face couldn’t stand his childish voice. The boy’s face smelled like stale fruit.

It was the smell of old women who put on so much powder it starts to wilt just like their skin. Women whose hands quiver in front of the mirror, who smudge lipstick on their teeth and then a little while later inspect their fingers against the mirror. Whose nails are buffed and ringed with white.

When the boy stood in the school yard together with the other children, the blotch on his cheek was the clamp of loneliness. And the spot grew, because slanting light was falling over the poplars.

* * *

Clara has dozed off in the sun, her sleep carries her far away and leaves Adina alone. The beating of rugs shatters the summer into shells of green. And the whoosh of the poplars contains the green shells of all the summers left behind. All the years when you’re still a child and growing and nevertheless sense that each single day goes tumbling off some cliff whenever evening comes. Days of childhood, with square-cut hair and dried mud in the outskirts of town, dust behind the streetcar, and on the sidewalk the footsteps of tall, emaciated men earning money to buy bread.

* * *

The outskirts were attached to the town with wires and pipes and a bridge that had no river. The outskirts were open at both ends, just like the walls, the roads and the lines of trees. The city streetcars went whooshing into the town at one of the ends, where the factories blew smoke into the sky above the bridge that had no river. At times the whooshing and the smoke were all the same thing. At the other end, farmland gnawed away at the outskirts, and the fields of leafy beets stretched far into the countryside. Farther away still was a village, the white walls gleaming in the distance looked no bigger than a hand. Suspended between the village and the bridge that had no river were sheep. The sheep didn’t eat the beet leaves, only the grass that grew along the way, before the summer was out they had devoured the entire lane. Then they gathered at the edge of town and licked the walls of the factory.

The factory was large, with buildings on both sides of the bridge without water. From behind the walls came the screaming of cows and pigs. At night their horns and hooves were burned, the acrid stench wafted into the outskirts. The factory was a slaughterhouse.

In the morning, while it was still dark, roosters crowed. They walked through the gray inner courtyards the same way the emaciated men walked on the street. And they had the same look.

The men rode the streetcar to the last stop and then crossed the bridge. On the bridge the sky hung low, and when it was red, the men had red cockscombs in their hair. The local barber told Adina’s father that there was nothing more beautiful than a cockscomb for the heroes of labor.

Adina had asked the barber about the red combs because he knew every scalp and every whorl. He said whorls are for hair what wings are for roosters. So even though no one could say exactly when, Adina knew that each of the emaciated men would at some point go flying over the bridge.

Because sometimes the roosters did go flying over the fences. Before taking off they would drink water out of empty food cans in the courtyards. At night the roosters slept in shoe boxes. When the trees turned cold at night, cats crawled into the boxes as well.

It was exactly seventy steps from the last stop to the bridge that had no river—Adina had counted them. The last stop on one side of the street was the first on the other. At the last stop the men climbed out slowly, and at the first the women climbed in quickly. Early in the morning they ran to catch the streetcar with matted hair and flying purses and sweat stains under their arms. The stains were often dried out and rimmed with white. Their nail polish was eaten away by machine oil and rust. And even as they rushed to catch the streetcar their faces already carried the weariness from the wire factory.

At the sound of the first streetcars Adina woke up. She felt cold in her summer dress. The dress had a pattern of trees, but the tops were upside down. The seamstress had stitched the material the wrong way.

The seamstress lived in two small rooms, the floor was full of angles and the walls had bellied out from the damp. The windows opened onto the courtyard. One window had a sign propped up that said COOPERATIVE OF PROGRESS.

The seamstress called the rooms the WORKSHOP. Every surface—table, bed, chairs, chest and even the floor—was covered with snippets and scraps. And each piece of fabric had a piece of paper with a name. A wooden crate behind the bed held a sack full of scraps. On the crate was a label NO LONGER OF USE.

The seamstress kept her clients’ measurements in a small notebook. Anyone who’d been coming for years was considered a longtimer. Whoever came rarely, by chance, or only once was a short-termer. If a longtimer brought some material, the seamstress didn’t need to take more measurements, except for one woman who went into the slaughterhouse every day and was as emaciated as the men—for her the seamstress had to take new measurements every time. She held the tape in her mouth and said, really, you’d be better off going to the vet and having him outfit you with a dress instead of me. Every summer you get thinner and thinner. Pretty soon my notebook will get filled up with just your bones.