The Friar and the Cipher (18 page)

Through it all, Dee remained in correspondence with Walsingham, and he and Kelley did manage to make contact with the Italian double agent Francesco Pucci. Pucci, a lapsed Catholic, was later accused of having bribed one of the pope's servants to copy letters written by Philip of Spain discussing the sabotage of a certain English forest that supplied timber for the queen's navy. The Spanish were planning to send a small band of men to burn down the forest so that the English would not be able to build new ships. Forewarned by Dee, Walsingham's men were able to intercept this troop before they did any damage.

But Dee also made enemies—Pucci was one of them—and was regarded with suspicion by members of Rudolph's court. It was whispered that he and Kelley were English spies. Kelley, ever the survivor, began to make side deals. The result was that Dee had to flee for his life while Kelley was embraced by the emperor and elevated to knighthood. Before he left, Dee had to surrender most of his valuables to Kelley, ostensibly to be used to bribe Lord Rosenberg, a powerful lord of the realm, for safe conduct. “Feb. 4th [1589], I delivered to Mr. Kelley the powder, the bokes, the glas and the bone, for the Lord Rosenberg; and he thereuppon gave me dischardg in writing of his own hand subscribed and sealed,” Dee wrote in his diary.

Dee came back from England to discover that his library had been vandalized in his absence. He lost five hundred volumes, and, although it was claimed that an unruly mob broke in, most of the books ended up in the libraries of other scholars. After his Bohemian adventure, Dee never regained his former influence at court, and his reputation as a scientist and mathematician went into decline. Walsingham died in 1590, still in the queen's service, having secured her safety by subverting the Spanish plans for the Armada and buying England enough time to prepare for the assault. According to Simon Singh, “After his death, it was discovered that he had been receiving regular reports from twelve locations in France, nine in Germany, four in Spain, four in Italy, and three in the Low Countries, as well as having informants in Constantinople, Algiers and Tripoli.”

His employer and protector dead, Dee lived the rest of his life in poverty, even resorting to selling his precious books to live; in the end he was exiled to a nondescript position in Manchester and died in relative obscurity around 1609.

As for Edward Kelley, for three years he was Rudolph's favorite, dubbed the “Golden Knight” for his alchemical triumphs, rewarded with estates and riches. He lived the life of a lord, moved in aristocratic circles, dressed in silks. Then, in 1592, he had an altercation with one of the emperor's retainers, killed his opponent in a duel, and was thrown into a dungeon for the crime. Rudolph thought to use this opportunity to pry out his alchemical secrets and had Kelley tortured, but since the secrets had more to do with subterfuge than science Kelley could not answer his interrogator's questions. In desperation, he tried a daring escape over the castle wall with a rope, fell and sustained internal injuries, and died soon after.

THERE WAS ONE MORE ELEMENT

to this story. While in Prague, around the year 1586, Dee's son Arthur remembered his father having a strange book, which he later sold for six hundred gold ducats to the Italian spy Pucci. This book, Arthur later told his friend Thomas Browne, was “a booke . . . containing nothing butt Hieroglyphicks, which booke his father bestowed much time upon: but I could not heare that hee could make it out.”

It is just about this time that the emperor Rudolph purchased a manuscript for the hefty sum of six hundred gold ducats. He believed this to be an original work by Roger Bacon, a man in whose magical and scientific achievements he had become extremely interested as a result of his sessions with John Dee. The odd thing about the manuscript was that it was written entirely in cipher.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Brilliant Braggart:

Francis Bacon

• • •

IT IS EASY,

particularly in the light of the later scandals in Bohemia, to dismiss John Dee's contribution to the advancement of modern science. But the follies of his twilight years and his increasing devotion to spiritualism mask his true legacy. In the fifty years dating from Dee's first commanding lectures on Euclid in Paris, the pace of scientific thought in England, moribund for so many centuries, had quickened perceptibly, so that what had appeared daring and innovative at mid-century was already outdated by 1600. That this was so, that scientific thought was capable of shaking off the shackles of superstition so decisively as to render John Dee's notions ridiculous in his lifetime, was due in no small part to Dee himself—or, rather, to Dee's library at Mortlake.

The library at Mortlake was an engine that helped fuel the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century, of which Britain was an undeniable leader. The presence of so many books, so easily accessible from London and therefore available to so many of England's best minds, jump-started the process of intellectual development in that country in the same way that the sudden influx of translated Greek manuscripts from Toledo had precipitated the scientific renaissance of the thirteenth century. Dee's library succored geographers and mathematicians, philosophers, explorers, and poets. There, at Mortlake, was the embryo for what would eventually grow into the colossus known as the Royal Society.

And since no one could enter that library and not feel the power of Roger Bacon's work, Bacon's thoughts entered the mainstream of English consciousness in a way that would not have been possible otherwise. John Dee had personally promoted the mystique of Roger Bacon, but his library advanced the thirteenth-century friar's ideas. These ideas were absorbed by many scholars, but one in particular stands out as Bacon's true intellectual descendant, the man who finally brought Roger Bacon's notion of experimental science into the sunlight, so much so that because they hold the same surname, the two are often confused: Francis Bacon.

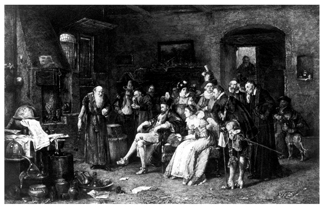

John Dee performing an alchemical feat for Rudolph II in a nineteenth-century painting

EDGAR FAHS SMITH COLLECTION, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LIBRARY

FEW IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY OR SCIENCE

have a larger presence than Francis Bacon, but the question is, as what? Genius, humbug, solitary scholar, stentorious self-promoter, loyal friend, ambitious betrayer, judge, thief, social climber, member of Parliament, mystic, experimentalist, original thinker, shameless plagiarist, and sometime reputed author of Shakespeare's plays—Francis Bacon was all of these and more. His proponents have pronounced him the father of modern science; detractors asserted that “few attempts at giving a new direction to the pursuit of truth have been more overrated.” Will Durant described him as “the greatest and proudest intellect of [his] age”; the social anthropologist Loren Eiseley called him “the man who saw through time”; and the scientific historian Lynn Thorndike said that “he was a crooked chancellor in a moral sense and a crooked naturalist in an intellectual and scientific sense.”

Francis Bacon was born in 1561, three years after Elizabeth ascended the throne. Like Roger Bacon, he was a younger son; his father, Nicholas, was the keeper of the royal seal, a position of great prestige. The most important member of the family was his uncle by marriage, the even more prestigious (and extremely wealthy) William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Elizabeth's royal treasurer and first secretary of state.

When he was twelve, Francis was shipped off to Cambridge for much the same reasons as had been Roger Bacon to Oxford 350 years before. When his father died six years later, Francis, by then in the queen's service, saw that his road for both position and money went through Cecil. But Cecil did not think much of his egocentric and crassly ambitious nephew. In one of his many entreaties to his uncle to provide a path to position and wealth that went unanswered, Bacon is famous for having said, “The objection of my years will wear away the length of my suit.”

The life of a gentleman seemingly beyond reach, Bacon turned to practical pursuits. He earned a law degree in 1582, showing such aptitude for the profession that he was soon lecturing, and then at age twenty-three got himself elected to Parliament, where he would remain a member for almost forty years. From here, Bacon spent much of the next decade currying favor with the powerful while serving in a series of minor roles in English government. In his free time, he began serious study of history, philosophy, and science. “I have taken all knowledge to be my province,” he wrote to Cecil, with the utter lack of humility that had already become his trademark, doing little to dispel his uncle's opinion of him.

Like every other scholar of the period, Bacon spent little time at the largely denuded university libraries. Rather, he sought out the best-stocked of the private libraries, and the largest and most extensive personal collection in England was at Mortlake.

Nicholas Bacon had been a friend of Dee's, and there is an entry in Dee's diary for August 11, 1582, indicating that twenty-one-year-old Francis had visited him and made use of his books. (Also present at that meeting was Walsingham's cryptographer, Thomas Philips.) There is no specific documentation of further visits, but it has long been suspected that Dee provided the young, prodigious Francis Bacon a detailed introduction to the work of his thirteenth-century namesake, even mentored him in experimentalism. Bacon's subsequent output in the sciences would more than bear that out. It was shortly after the Mortlake visit—or visits—that Bacon began work on a vast scientific project on which he would labor for the rest of his life. It was also about this time that he developed a lifelong interest in ciphers.

*5

It would be more than two decades, however, before Bacon would write publicly on science. During Elizabeth's reign, he wrote mostly on politics and ethics, showing such foresight that a seventeenth-century observer noted that, had his ideas been adopted, “all the troubles of the next forty years might have been avoided.” Foresight did not make Bacon popular at court, however. Convinced that unity would serve England more than discord, he issued a paper in favor of religious tolerance that piqued both the queen and Cecil. Both made it clear to Bacon that if he wished to advance himself—a desire of which he made little secret—he was going to have to keep his mouth shut and play along. Bacon, however, was unwilling to suppress opinions that he was convinced were the most enlightened in England (and probably anywhere else). In 1593, to demonstrate his unwillingness to kowtow to the aging Cecil or the intractable Elizabeth, he publicly declared himself opposed to the queen's plan to raise taxes.

Elizabeth was furious, and Bacon was shunned at court. The direct road to power now cut off, Bacon was forced to cast about for a new sponsor. He found one in Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex, a man of his own generation and disposition, and there is nothing that epitomizes the extremes of Bacon's public life and reputation more than the course of their friendship.

Essex, five years Bacon's junior, was handsome, brave, intelligent, headstrong, passionate, and a favorite of the queen's, even rumored to have been her lover. (Errol Flynn played him in the movies, too, in

Elizabeth and Essex

.) He became both Bacon's friend and patron, while in turn Bacon provided counsel as to how Essex might increase his power in the government (and by association, Bacon's own), something the ambitious earl was chafing to do. In the early 1590s, the grateful Essex pushed for Bacon to be named attorney general, a plan foiled by Cecil himself, who instead prevailed upon Elizabeth to appoint the more agreeable Edward Coke. Essex consoled Bacon by granting him an estate at Twickenham and a stipend of £1,800 to keep it up.

In 1598, Cecil finally died, and, once again largely through the efforts of Essex, Bacon was appointed Queen's Counsel, part of a group of lawyers who, in addition to their judicial tasks, advised the Privy Council. Soon after, Essex committed a series of political blunders (all against Bacon's advice) and, almost impossibly, succeeded in alienating Elizabeth's affection. Finally, in 1601, he joined in a plot (with Mary's son, James VI of Scotland, among others) to raise an army and take over the government. When he was caught, it was Bacon who was charged with drawing up the indictment. Bacon, torn between political suicide and betraying his closest friend, chose the latter. Not only did he present the indictment but, when Coke appeared to be botching the job at the trial, pled the case himself. Essex, proud and gallant until the end, freely confessed his guilt and a few days later was executed on Tower Hill. His severed head remained on public display for a year.

If Bacon's ambition and ego were colossal, so was his capacity for achievement, and it was only after Elizabeth's death and the ascension to the throne of Essex's collaborator James VI (now James I of England) that all of these would find their outlets.

As soon as the new king was in place, Bacon wrote a long, fawning letter proposing a brilliant candidate for high public office—himself. James, not altogether enamored of the man who had prosecuted Essex, ignored the suggestion but did throw the supplicant a bone by including Bacon in a list of three hundred new knights. Undeterred, the now Sir Francis continued to pester the king with missives, suggestions for improving government, stressing his favored themes of ethics, unity of purpose, and conciliation. For all the erudition, however, Bacon continued to be disregarded.

Then, in 1605, Francis Bacon published the first of his great scientific works. Much as Roger Bacon had proposed that Clement reform education and rebuild the trivium and quadrivium from the ground up, this work, which Francis Bacon called

On the Dignity and Advancement of Learning,

was a proposal to completely redefine the role and manner of education in English society.

As Roger Bacon began with a tribute to the pope, Francis Bacon began with one to the king. Taking no chances, he made this tribute even more obsequious than those before it. “I have been often struck with admiration, apart from your other gifts of virtue and fortune, at the surprising development of that part of your nature which philosophers call intellectual,” he wrote to a king considered not particularly bright. “The deep and broad capacity of your mind, the grasp of your memory, the quickness of your apprehension, the penetration of your judgment, your lucid method of arrangement, and easy facility of speech . . .”

Bacon then noted, “Since your majesty surpasses other monarchs by this property [the learning of a philosopher] . . . it is but just that this dignified pre-eminence should not only be celebrated in the mouths of the present age . . . but also that it should be

engraved in some solid work which might serve to denote the power of so great a king and the height of his learning

” (italics added).

All that groveling notwithstanding, what followed was truly groundbreaking—

The Advancement of Learning

was as close as anyone in Europe had come to calling for universal education. Bacon insisted that learning be pursued both for its own sake and for its practical benefits to society. Although he never actually wrote “knowledge is power,” a saying for which he is most famous, he was to later state that “knowledge and human power are synonymous.” This sense of practical utility was precisely what Roger Bacon had stressed so strongly to Clement in his plea for the reform of scholasticism. He had promised Clement military, civil, and even ecclesiastical benefits from a more empirical view of the world—a stronger and more vibrant Christendom—and so the more secular Francis Bacon assured James that the spread of learning would result in a stronger and more vibrant England.

There would be objections to be overcome, however—some sincere, some self-serving, but all misguided—and once more Francis Bacon looked to the same culprits as had Roger. Instead of the tyrannical Dominicans whom Roger Bacon blamed for the perpetuation of ignorance, Francis Bacon denounced “arrogant politicians” and “zealous divines,” but the litany of excuses for an uninformed populace was the same—that educated men would not make good or willing soldiers (or churchgoers), that they would be less accepting of the rules of king or Parliament (or pope), that it would make people indolent and slothful (or questioning).

In the second part of

Advancement of Learning,

Bacon provided a detailed breakdown of all possible areas of inquiry, noting which had been explored and which needed further study. As with the

Opus Majus, Advancement of Learning

stressed the study of empirical science in the pursuit of general knowledge. Physics, experimentation, invention, medicine, natural history, anthropology, botany—not only are all of these mentioned prominently, but many are singled out by Bacon as those areas where further investigation is most warranted.