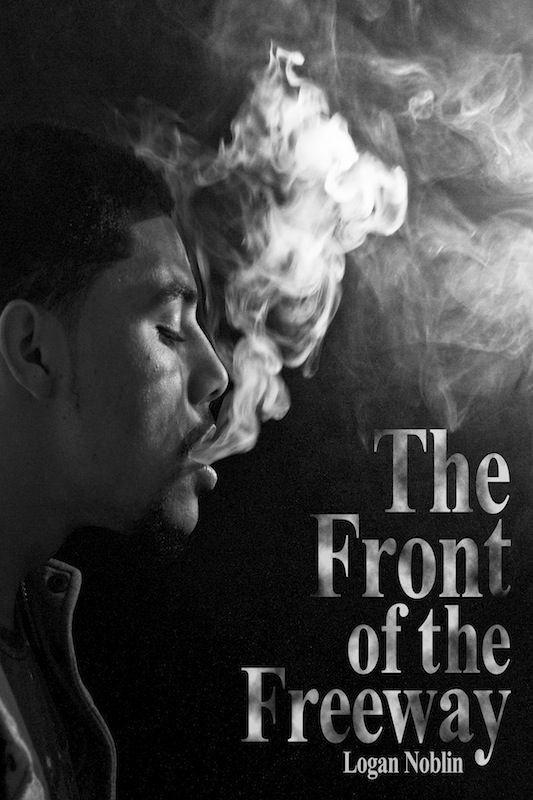

The Front of the Freeway

Read The Front of the Freeway Online

Authors: Logan Noblin

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Literary, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Urban Life, #General Fiction

The Front of the Freeway

By Logan Noblin

Copyright 2012 by Logan Noblin

Cover Copyright 2012 by Joey Everett

and Untreed Reads Publishing

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be resold, reproduced or transmitted by any means in any form or given away to other people without specific permission from the author and/or publisher. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to the living or dead is entirely coincidental.

By Logan Noblin

When I was a kid, I thought there was a front of the freeway—that somewhere way up in front of all the cars, in front of all the lights, someone was in first. Someone was winning. Someone had to be. And I always thought that, if we could just drive a little bit faster, just pass a few more cars, I would win. I could be in front of everybody, the glowing pearl eyes of a thousand headlights falling back over the horizon in the rear-view mirror. I knew that, if I drove fast enough, nobody would ever catch me. But that’s when I was a kid.

By high school, my wrestling coach told me just how big the world was. “There’s always somebody out there better than you,” he’d say, “and probably somebody worse.” But to be honest, he spent a lot more time talking about the ones who were better. Mr. Stevens, my counselor, a sagging, empty frown in a pressed beige sweater-vest, called me into his office to tell me that, with my grades, a four-year college was out of the question, but if I worked hard, I could graduate JC, and then at least I wouldn’t be one of those community college dropouts. Then my father told me to start paying rent or start sleeping at the park, so I sort of fell behind the community college track and into the back of Romeo’s Deli. I mean all the way in the back, washing dishes and learning Spanish. My first three months there I thought my Spanish name was

Gringo

.

It’s not like I was the only English voice in the building, though. Out behind the deli, Tony, the lanky black sandwich boy with a cocaine white smile, took orders from strangers because everybody liked Tony, and Tony seemed to like everybody. You’d get the feeling Tony knew a thing or two more than you about just about everything, and I always thought he was remarkably well informed for a sandwich boy and a high school dropout. Eventually, Tony taught me two very important lessons. First, that I was wrong. Nobody’s winning this race. We’re just a bunch of little cars passing each other and falling behind, and some of us are just limping between lanes with a busted taillight and a flat tire. But the second thing he taught me was how to get out of it. And I’d come to owe him for that, because if not for Tony, I would have stayed in

Romeo’s Prison

taking

Romeo’s Orders

becoming

Romeo’s Bitch.

The laws of God, the laws of man

He may keep that will and can

Not I: Let God and man decree

Laws for themselves and not for me.

—A. E. Housman

Deep breath.

Every morning I tell myself the same thing, take a deep breath. It’s December, and it’s 6:00 in the morning. Even in Southern California the air is frozen stiff. An hour bus ride through the dark, biting cold isn’t the worst, even on the clotted artery of a congested Los Angeles freeway, but when the air is frozen stiff, the ground is frozen, too, all the way down to the frost-bitten metal pipes pumping ice-water under the city’s skin like so many cold metal veins. The dish soap isn’t any better, a slender tube of chilled yellow slime, so every morning before I plunge my hands into a sink full of numbing, 32.01 degree dishwater, I tell myself the same thing.

Deep breath.

The water could be scalding, the burn’s the same, at first, a thousand needles pricking and cutting like two fish-hook gloves, but whether the hours of quick, clockwise scrubbing warms my hands, or if the nerves simply lose feeling, either way, the first plunge is always the worst. Rodrigo won’t turn the water heater on until he staggers into the deli for 9:00 opening, so for now the shiny red ring wrapped around the hot water nozzle is an open, laughing mouth with a cold metal tongue. I grab the tongue and twist hard to the right, but the slick silver faucet spits only ice into the frothing antibacterial swamp.

6:45.

A tall sheet of zinc slaps hard against a frail tin frame as the new sandwich boys clamber through the back door fifteen minutes early. The old sandwich boys will file in fifteen minute late, and by 7:30 the wet musk of mayonnaise, vinegar, processed cheese, fish oil, gas, and ammonia-based cleaner will invade the washroom and choke the cramped plaster cell. Even as the kitchen groans from the cold and empty quiet of early morning to the hot and jarring loud of opening hours, my cell is empty, nothing but sloshing dishwater, the stench of the kitchen, and me. The cooks scramble between ovens and boiling pots in the kitchen as an endless line of customers paces anxiously behind a long glass counter out front, but that’s all on the outside. Even the bus boys don’t come back here if they can help it, because I don’t speak Spanish so, as far as they know, I’m a mute. There’s no TV, no radio, and no employee of the month plaque, either. There’s mold on the walls and a big metal sink…and soap, there’s always plenty of soap.

It’s Tuesday, I think.

I’ve never liked Tuesdays. The improbable optimism of the weekend—your friend’s shitty house party, a beer on the beach, whatever it is—it drowned in the sink early Monday morning, and Saturday’s a short eternity away. This isn’t a day job, either. I got over that notion a year ago. This isn’t temporary, and this isn’t going away. There are no incentives, no promotions, no mobility, no escape. There’s one check every two weeks, and it’s never quite enough to get to the next one. This is ten hours a day, every week, so for now it’s soap, scrub, rinse. Soap, scrub, rinse.

“Hulian!” It’s 12:00 and Rodrigo’s yelling. “Hulian! Why you didn’t finish the saucepans first, huh?

Sabes que

, clean the saucepans, then the dishes. Come on,

gringo

!”

Soap, scrub, rinse.

For the next ten hours, I won’t clean a single dish. For every plate I wash, for every bowl I scrub, another grease-swabbed, crumb-crusted stack of platters appears on the cold metal counter beside me like plastic mitosis. If I have to see Rodrigo’s enormous Ecuadorian mouth flapping through the washroom door one more time, I might gut him with the chef’s carving knife.

Soap, scrub, rinse.

It’s 12:00, so I’ve got exactly two hours until my unpaid thirty-minute lunch break. Despite spending most of my shift with my hands submerged in a tank of bubbling yellow disinfectant, it is strict company policy that I wash my hands for a full thirty seconds before and after my break. And if I clock out two minutes early or two minutes late, or if I extend my break by more than two minutes of the time allotted, then I’m going to be in strict violation of some shit I really don’t care about.

“

Aqui

.” A bus boy drops a stack of grime and plastic onto the stainless steel tray next to the counter. First the saucepans, then the dishes. Then my head might just explode, and between the blood and brain, I’ll have to clean the silverware all over again.

It’s 2:00, and I’m allowed to eat. I report to the punch clock, salute, and drop my timecard through a narrow slit in the machine’s plastic skull.

Whir, click, punch.

The machine hiccups the timecard back into my hand, time and date faintly branded across the top of the pale white paper.

Usually, I slip into the walk-in freezer for lunch and dig up an expired, but free, egg or tuna salad, resting for a few quiet minutes under the placid monotone of an industrial fan droning in cyclical indifference. Stepping into the walk-in feels something like falling into the Arctic. The cold wind, the failing light, the solitude—an oasis of frost and metal separated by twelve steel inches from the heat and hurry of the kitchen. I tug hard on the heavy iron door, and it gives, a cool mist seeping out from around the frame. But heaving the thick iron door ajar, I glance up and realize that, today, I’m not alone. Two shadows melded together in the corner speak quickly in hushed tongues. More Spanish.

“Eres un ladron, hombre.”

“Quizas, pero soy tu mejor amigo si quieres más de esa, chico.”

Like a reverse pick-pocket, one shadow slips a folded wad into his jeans, coolly, precisely, but not quickly enough to escape my attention. The other unfolds from the wall and materializes in the dim light, his hands buried deep in his cargo-shorts pockets. But before I can edge from the room, the shade glances up, and I’m snared in a wild, petrified stare. Martín the bus boy freezes, mouth agape, his face twisted in bewilderment like a deer caught in a bear trap. His slender figure trembles slightly in the dark, his nervous, skittish eyes pacing frantically across his face at about my chest height, and neither of us says a word. I always liked Martín. He’s as mute as I am around here, scrambling silently between dirty tables like the house rat, and if I’m on the outside of some great joke, it’s a small comfort knowing he’s out with me. But for now we just watch each other until my gaze sinks and a muttered apology dies somewhere in the back of my throat. Martín’s head snaps around, grasping for a cue from the shadow still blanketed in darkness.

“Esta bien, vete.”

With that, Martín scurries from the tundra like a startled mouse, leaving me alone with a voice charming enough to eclipse the groaning industrial fan. “What’s going on JT?”

“Hey, what’s up, Tony?”

“Just chillin’, man. Just chillin’.” Nobody hangs out in a 38 degree metal locker except frozen lasagnas and employees hiding from something. We both know that, but I don’t mention it. I just nod and mutter something and grapple for an exit line. “You like working here, JT?” I hate working here. I hate every dirty dish, every bitching customer, and every accented word out of Rodrigo’s incessant, nattering mouth. We both know that, too. But I know better than to breathe a word against it.

“Yeah, it’s alright, you know.” The slick black coils of Tony’s snakeskin watch glisten against his charcoal skin in the dark. I always thought he looked remarkably well dressed for a sandwich boy and a high school dropout, but I don’t mention that, either.

“You’re a liar, JT.” Tony’s laughing now, a song that echoes and dances about the industrial ice cavern. “This place is a prison.”

“Yeah, well, it’s work.”

“Yeah, man,” he laughs. “It’s work.” Tony’s breath condenses in the frostbitten air and rises, a cool ring of mist floating gently to his forehead and dispersing. “I want to show you something, JT. Tonight.” Tonight? I couldn’t have mumbled more than five words at the guy in the last two years and now he wants to take me a on a field trip.

“What is it?”

“I’ll pick you up out front Grand Central Liquor at twelve. And don’t even start with the bullshit; it’s Tuesday night and I know you don’t have anything better to do.” Before I can fumble over an alibi and dumbly breathe

uuhhh

…, Rodrigo tears the sealed door open and a cascade of light floods through the gaping iron wound.

“Oye, Tony, we need you out front.” Tony smirks and stares I’ll be there when I get to it into the open doorway, but after a second he gives, kicking himself from the wall and striking up in hummed sarcasm the melody of an old slave spiritual. With the compressed thud of the closing steel door, the light and Tony’s song vanish, leaving me standing alone and confused in the solitude of my little Antarctica.

“Men talk of killing time, while time quietly kills them.”

—Dion Boucicault

Tony’s right. It’s Tuesday night, and I don’t have anything better to do. I never do. Go to work, make dinner, go to bed. If my dad passes out on the couch and I can steal the remote for the night, it’s a blessing, because that’s part of his routine. Go to work, make dinner, watch TV. He’ll probably finish a fifth of Jack Daniels in there somewhere, but I guess that’s because of work, so it all fits the schedule.

My dad’s a cop. If there’s anything worse than being twenty-one and living alone with your father, it’s being twenty-one and living with a cop. Cigarettes, friends, girls, whatever—not under his roof. Mom was more reasonable, which isn’t saying a whole lot, but I guess that’s why she bugged out. Dad called her a loose cannon and a bottle of tequila, the type that can’t stay still for too long. He hated that about her. She cried for the first few months and yelled for the last few, creeping in at 4:00 every morning while Dad snored at the TV, the History Channel still flickering important nothings at him across a dark living room. He loves the History Channel. Every night at 8:00 he sits down to watch important people live their lives while he loses his in front of the television. But it’s all part of the schedule, so at least he’s always on time.