The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (21 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

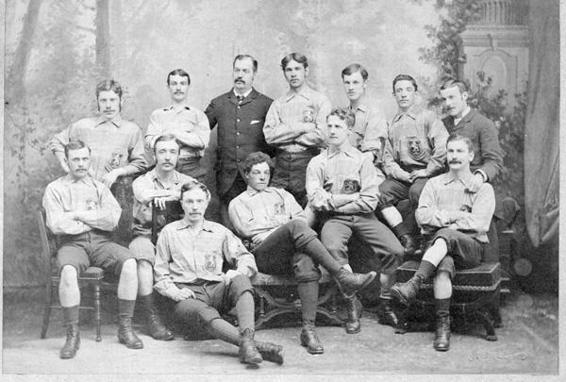

Authors: Gary Ralston

Scots Wha Hae: the Scotland team that defeated England 6–1 at The Oval, London, on 12 March 1881. The side included three Rangers – Tom Vallance, back row, centre. Forward David Hill, middle row, left; with George Gillespie (now goalkeeper, no longer a back) second from right in the middle row. Harry McNeil is middle row, far right. The match was especially significant as it marked the first time a black player, Andrew Watson of Queen’s Park, played international football. (Picture courtesy of Scottish Football Museum.)

Were he playing today, Vallance would command a substantial seven-figure transfer fee, but in those innocent, amateur days football was only a pastime for most. Looking to the future, Vallance decided to leave his lodgings at No. 167 Govan Road in February 1882 and forge a career on the tea plantations of Assam in India. It was a bold move as it was a fledgling industry that had only become commercially exploited in the previous 50 years. However, conditions in the north east of India were far from idyllic. Assam historian Derek Perry (5) has painted a picture of a remote, lonely region at the time of the emigration of Vallance. The conditions would have been daunting, even for a man such as Vallance at his physical peak, but he had little chance to settle as he was struck down by illness within a few months of his arrival. On the basis of later accounts, particularly those which reveal that the illness compromised his football career on his return to Scotland, Perry suggests he was likely debilitated by the dreaded Kala-azar, or black water fever, a form of pernicious malaria. Another attack could have been deadly and it was in light of concerns about his health that Vallance returned to Scotland after only a year away. He played three times for Rangers in season 1883–84 but was a spent force. He kicked his last ball for the club in a 9–2 win over Abercorn at Kinning Park on 8 March 1884. The Scottish Athletic Journal sadly noted: ‘He still had a fancy for the game of football and donned the jersey several times but his eye was dimmed and his leg had lost its cunning and he was not even the shadow of his former self.’6

His illness had clearly forced Vallance into taking stock of his life and soon after his return from India he abandoned his earlier aspirations of pursuing a career as an engineer to become a travelling salesman in the wine and spirits trade, opening the door to a new and lucrative existence in the hospitality industry. He was employed by James Aitken & Co. Ltd, brewers who operated from Linlithgow and Falkirk, brewing their popular ‘Aitken’s Ale’. His working life quickly back on track, Vallance also set about re-establishing himself at Kinning Park. If he could not do it on the field any longer, he could certainly contribute off it and he was elected club president for the first of six seasons in May 1883.

During his 12-month absence John Wallace Mackay had come to the fore at Kinning Park. Vallance honourably resigned early in his presidency after that player coup moved to remove him as umpire for a match at Dumbarton and replace him with Mackay because he would not favour his own team in his decision making. However, ’keeper George Gillespie issued a grovelling apology on behalf of the team and Vallance returned within a week, his grip on his portfolio tightened still further. As a salesman he was undoubtedly used to flattery and cajolery to get his own way, but there also appeared to be a genuine streak of honesty and integrity running through Vallance to which people warmed. For example, he was an arch critic of Mackay and frequently stood up against the worst excesses of the honorary match secretary in his seemingly never-ending spats with the Scottish Athletic Journal. On one occasion, following the half-yearly meeting in November 1884, Mackay attempted to coerce Vallance into lying on his behalf by denying claims in the Journal that the match secretary had said Queen’s Park were on their financial uppers ahead of their move to the second Hampden Park. In a fit of pique, Mackay had also recommended Rangers never play Third Lanark again after their Glasgow rivals reported them to the SFA for the ‘Cooking the books’ scandal. Vallance refused and, not surprisingly, was showered with praise the following week by the newspaper.

Increasingly, Vallance was dealing from a position of presidential strength as Rangers moved from a period of financial uncertainty to one of stability under his reign. Membership numbers increased and, with a far-sighted and energetic committee at the club, a move to the purpose-built first Ibrox Park was secured. However, Vallance missed the grand opening of the new ground against Preston North End on 18 August 1887 as he married Marion Dunlop, sister of former teammate, club president and friend William. Marion was from Glasgow and was six years Tom’s junior. The wedding ceremony was held in the Dunlop family home, with Tom’s younger brother Alick acting as best man.

Within 18 months the couple’s first child was born, Harold Leonard Vallance, on 20 January 1889. By this time they lived at No. 89 Maxwell Drive in the south-west of Glasgow, before moving back into the city to No. 48 Sandyford Street a year later. It was at this point that Tom’s career was suddenly injected with an extra impetus, as he moved from his position with brewer James Aitken to become a successful restaurateur. In 1890 he took on his first real business venture – a pub/restaurant located at No. 22 Paisley Road West at Paisley Road Toll. He called the restaurant The Club and it quickly became a popular venue for the Rangers’ ‘smoker evenings’. He would also go on to own and operate at least two other restaurants in the city: The Metropolitan at No. 40 Hutchison Street and The Lansdowne at No. 183 Hope Street. His reputation among his business contemporaries was underlined in 1906 when he became president of the Restaurateurs and Hotelkeepers Association.

The happiness of Tom and Marion was sealed still further in 1891 when another son, James Douglas, was born. The Vallances seemed to lead a somewhat itinerant life at this stage as James was born in the new family home at No. 219 Paisley Road in Glasgow, before they moved to nearby Lendel Terrace then, soon after, Maxwell Drive and back to Kersland Street in the west end. Finally, in 1908 Tom and Marion settled at No. 189 Pitt Street in Glasgow city centre and the place they would call home for the rest of their lives.

In addition to his work with Rangers and his various business concerns, Vallance was also a member of the ‘Old Glasgow Club,’ a local history society. He also found time for another passion: art. Self taught, he exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Royal Glasgow Institute at least twice, in 1897 and 1929, and his work was also displayed by the Scottish Academy. He never became as celebrated as contemporaries such as Glasgow Boys James Guthrie and James Paterson, or Scottish colourists Samuel Peploe or John Fergusson, but his work was popular and still occasionally appears at auction. One of his final commissions was an impressive and dramatic canvas almost six feet in height entitled The Charge, which was presented to Cadder Golf Club in Bishopbriggs on its opening in May 1935. The painting, which featured an army battalion on horseback, was so impressive it was even reproduced in the Daily Record in February 1934. Unfortunately, despite its size, the golf club lost track of the painting when it was removed during World War Two and its current whereabouts is unknown.

Sadly, the events of World War One were to have a lasting impression on the Vallance family. Harold Vallance joined the 7th Battalion (Blythswood) of the great Glasgow regiment, the Highland Light Infantry. Tragically, on 28 September 1918, just six weeks before the end of the war, Second Lieutenant Harold Leonard Vallance, aged 29, was killed in one of the closing conflicts in the assault on the Hindenburg line in France. He was buried with honour at Abbeville Communal Cemetery.

A reproduction of The Charge by Tom Vallance, which appeared in the Daily Record in February 1934. The original oil painting, a six foot tall canvas, was presented to Cadder Golf Club ahead of its opening in 1935.

Thankfully, the story involving second son Jimmy has a much happier ending. He married Elizabeth Wilson and moved to England to continue the family’s football tradition. Jimmy became trainer for Stoke City and helped the side win promotion to the First Division under team manager Tom Mather in 1932. One of the emerging stars of the club at that period was Stanley Matthews, who married Jimmy’s daughter Betty in the summer of 1934 at Bonnyton Golf Club in Eaglesham. Their courtship had started 12 months previously when Jimmy invited Stanley to his holiday home in Girvan to teach him how to play golf. In fact, Stanley’s relationship with Betty was sealed over a four ball in the Ayrshire town involving Stanley, Betty, Jimmy – and Sam English. The Rangers striker, so unfairly tarnished by many rival fans following the tragic and accidental death of Celtic ’keeper John Thompson at an Old Firm game at Ibrox in 1931, was also a family friend of Jimmy Vallance who, by the time of his daughter’s marriage, had moved from Stoke to become golf manager at Bonnyton.

Betty, who became Lady Betty following Sir Stanley’s knighthood in the New Year’s Honours List in 1965, died in November 2007 aged 95, seven and a half years after her husband passed away. Sir Stanley, the first superstar of football, played until he was 50 and left a rich sporting legacy from his spells with Stoke and Blackpool. He also won 54 caps for England and was the first European Player of the Year in 1956. The Vallance connection with Rangers clearly held good, however, as Matthews guested for the Light Blues twice during World War Two, including a medal-winning appearance in the Glasgow Charity Cup Final of 1941 when Bill Struth’s men saw off Partick Thistle 3–0 at Hampden in front of 25,000 fans, courtesy of a Torry Gillick double and a strike from Alex Venters.

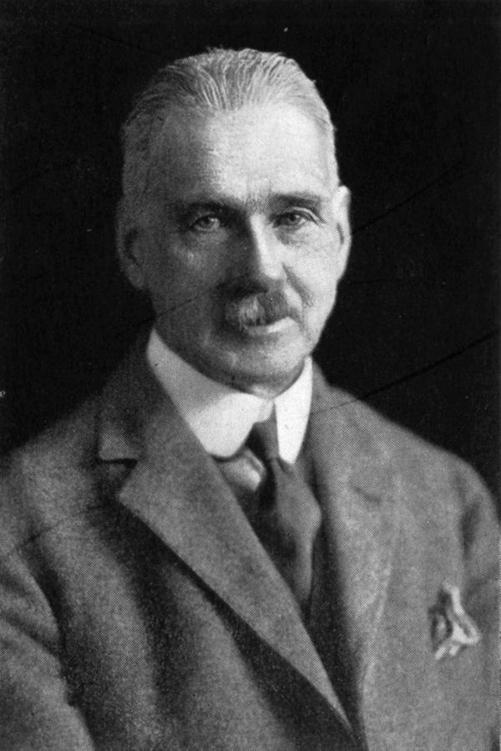

Senior statesman: Tom Vallance, pictured in the 1920s.

Jimmy’s son Thomas, born in Stoke in 1924, was also a footballer of some promise. He played for his home-town club during World War Two and also had a short-lived spell at Torquay before moving to Arsenal in 1947. A left-winger, he made his debut for the Gunners the following season and played 14 times, scoring twice. However, competition for places at the North London club was fierce and he played only once in the following campaign before becoming a reserve-team regular, finally being freed in the summer of 1953.

By that time his grandfather Tom had long since passed away although, fittingly, he was given the Ibrox equivalent of a state funeral following his death at home on the evening of Saturday 16 February 1935, with his burial three days later at Hillfoot Cemetery in Bearsden. Rangers chairman James Bowie took one of the cords as the gallant pioneer was laid to rest, while former teammate James ‘Tuck’ McIntyre, also in his late seventies and one of the oldest surviving former players at the time, took another. Bill Struth attended, along with other senior club officials, while a host of former opponents from clubs such as Dumbarton, Clyde and Third Lanark also turned out. In life, some people are lucky if they experience shades of grey. Tom Vallance led an existence that was a riotous rainbow of colour, with the prevalent shade always that of the Rangers blue.

Happily We Walk Along the Copland Road