The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (4 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

Furthermore, that first written review of Rangers, by William ‘True Blue’ Dunlop in 1881, is also adamant the club was formed in 1872 – late March to be precise – by the three lads from the Gareloch and William McBeath as they strolled in Glasgow’s West End Park. Naturally, Dunlop was writing closer to the club’s birth date than anyone, so his evidence carries more authority, although, intriguingly, he claimed the young Rangers were inspired to form their club by watching the exploits of other teams at the time, including Queen’s Park, Vale of Leven and Third Lanark, yet the latter club, who survived until 1967, were not formed until December 1872. Likewise, Vale of Leven did not appear on the scene until the second half of 1872, when Queen’s Park accepted an invite to teach locals in the Dunbartonshire town of Alexandria the rudiments of the new game of association football, luring them away from their previous and long love affair with shinty.

If Moses McNeil, writing in the 1920s and 1930s under the influence of Allan, was convinced the club was formed in 1873 then Vallance, speaking much earlier in 1887, believed otherwise. At the grand opening of the first Ibrox Park in August of that year, at the Copland Road End of today’s stadium, he toasted the future of the club. In his speech, printed in the press at the time, he stated: ‘Well, about 15 years ago, a few lads who came from Gareloch to Glasgow met and endeavoured to scrape together as much as would buy a football and we went to the Glasgow Green, where we played for a year or two. That, gentlemen, was the foundation of the Rangers Football Club.’10

Former player Archibald Steel, who played for the club in the 1870s before moving to Bolton, wrote one of the first authoritative histories of Scottish football in 1896 under the pen name of Old International. His book 25 Years Football mines a rich seam of anecdote and first-hand experiences of playing against almost all the major clubs in the early years of the game in Scotland. Steel named 1872 as the year of Rangers’ foundation as he recalled: ‘In the west, particularly, the game quickly took root and any spare ground where football could be followed was seized upon with avidity by the eager aspirants to dribbling proficiency. Two of the earliest I may mention were the Queen’s Park juniors and the Parkgrove, besides which a year later – in 1871 – the Dumbreck and in the 12 months afterwards the Clydesdale, Rangers, Rovers and Third Lanark.’11

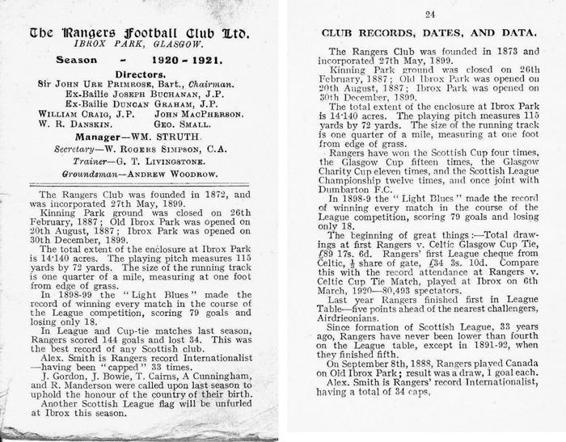

The Wee Blue Book of season 1920–21 acknowledged the year of the club’s formation as 1872. No reference was made in the club publication in either of the following two years, but by 1923–24 the date had been changed to 1873, without explanation.

If the formation date of the club has caused confusion down the years there is less ambiguity about the origins of the Rangers name. Allan’s early Rangers’ history, while largely sanitised, contains more than just kernels of truth. A flattering profile of Harry McNeil, the great Queen’s Park winger and occasional Ranger, in the Scottish Athletic Journal of 27 October 1885 reads like a Victorian version of Hello magazine and credits him with naming the club. Likewise, True Blue claimed the club was named Rangers as rudimentary rhyming slang after the fact so many of its earliest players were strangers to Glasgow.

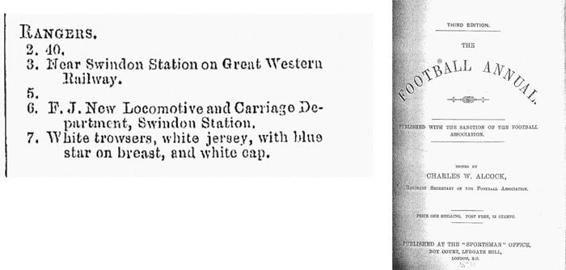

Neither tale rings as true as Allan’s account in his book that ‘Moses McNeil proposed that it should be called the Rangers Association Football Club and to the young minds the name had an alluring appeal. It was adopted unanimously. Mr McNeil has related that he had been reading C.W. Alcock’s English Football Annual and had been attracted by the name he had seen belonging to an English rugby club.’12 McNeil’s claims, made through Allan and again in the pages of the Daily Record in 1935, hold water. Alcock’s annuals were elementary guides to the newly formed clubs across Britain and their preference for the various codes of football, including association and rugby. They were first published in 1868 and are so rare that even the British Library does not boast any copies dating from before 1873. The RFU Museum at Twickenham does, however, and their issues make for fascinating reading.

Before 1870 no rugby team in England featured the Rangers name, although other wonderful handles included the Mohicans, Owls, Pirates and Red Rovers. However, in the 1870 edition of Alcock’s annuals a team called Rangers does appear, based in Swindon, with a kit that included white trousers, white jersey with a blue star on the breast, and a white cap. The Rangers football team that lost the Scottish Cup to Vale of Leven after three games in 1877 were pictured in the photographer’s studio shortly afterwards in a very similar kit, including the blue star on the breast of their shirts, but it can be no more than a coincidence as the blue star arguably owed more to their connection with Clyde Rowing Club, who used it then (and still do now) as their club emblem.

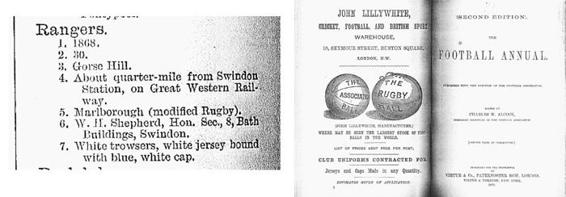

In Alcock’s 1871 edition Rangers are again mentioned, still at Gorse Hill in Swindon, but with the additional information that they had been formed in 1868 and played a form of rugby known as Marlborough. If it is accepted that Rangers were formed in the spring of 1872, as the weight of evidence suggests, and Moses McNeil named the club immediately, then the Swindon rugby team are the club from whom the Glasgow side took its name. Still, as always, there is scope for debate, because by the publication of the next edition, in the autumn of 1872, the Swindon club had disappeared and another club named Rangers (formed in 1870, but making its first appearance in Alcock’s annual) had taken its place. This second club played rugby union and were based on Clapham Common in London. They were listed next to a club named Old Paulines – from Battersea Park to the south of the Thames, not Walford in the east. Another rugby union rival, from Stamford Hill near Stoke Newington, was named Red, White and Blue. Now, would that not have been a name for Moses to have contemplated?

The Alcock Annual of 1870: the Rangers name appears for the first time, belonging to a club in Swindon (not specified as a rugby team until the 1871 edition) and with a design of kit similar to the one in which their Glasgow namesakes were pictured in the aftermath of their Scottish Cup Final appearance in 1877.

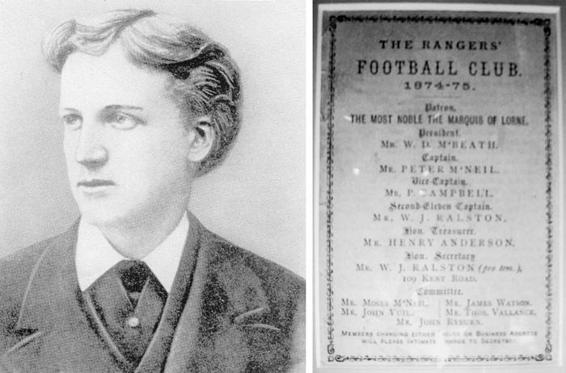

The year of formation and the origins of the club name may still inspire debate almost 140 years later, but what cannot be doubted is the royal connection Rangers were able to boast in its very infancy, as a membership card from season 1874–75 announced the patron of the club as the Most Noble, the Marquis of Lorne, who would go on to become the 9th Duke of Argyll. Unfortunately, the reasons behind his formal relationship with Rangers have been lost in the mists of time as the minutes of the club from that era no longer exist, while the archives from the Duke’s ancestral seat at Inverary Castle sadly, for the most part, are closed to the general public and have yet to undergo indexing.

However, it is clear that the new association football clubs saw patronage by the aristocracy as lending authority to their new ventures – not to forget, of course, the financial support that often came with the acceptance of an honorary position at the fledgling clubs. Queen’s Park, for example, charged captain William Ker with finding a patron in 1873 and he immediately set his sights on the Prince of Wales, who politely declined. The Earl of Glasgow, however, agreed and quickly forwarded a donation of £5 to his new found favourites. In all likelihood the Marquis of Lorne, John Douglas Sutherland Campbell, better known as Ian, would have donated a similar sum to his fellow lads from Argyll to boost their new enterprise. The Marquis was 27 years old when Rangers were formed and clearly had a level of interest in the association game as he was also an honorary president of the SFA at the time and was still listed as a patron of the association in the 1890s. It was something of a coup for the Rangers committee to persuade him to patronise their infant venture, not least because only a year earlier he had married Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, at Windsor, and had become one of the most high profile figures in British public life even if, as a Liberal member of parliament, he was regarded as something of a political plodder on the back benches at Westminster.

The Charles W. Alcock Football Annual from 1871. Rangers, from Swindon, are listed and confirmation is given of their preference for the Marlborough rugby code of football, as opposed to the association game.

As future Clan Campbell chief, the Marquis of Lorne is likely to have been acquainted with John Campbell, his namesake and father of Peter, who would have enjoyed a position of standing in the Argyll community as a result of his successful steamboat enterprises. The McNeils would also surely have had access to high society, even if indirectly, through their father’s position as head gardener at Belmore House on the shores of the Gare Loch. The Marquis, or Lorne as he was best known, was also a keen supporter of sporting pastimes, particularly those with an Argyll connection. The landed gentry viewed patronage of such healthy pastimes as an extension of their traditional responsibilities as clan chiefs, even in the latter half of the 19th century. In many instances, they would make prizes available or give financial support through an annual subscription to cover the cost of hosting get-togethers in sports such as shinty, cricket, curling, bowls and football. In addition to Rangers and the SFA, Lorne was also a patron of the Inverary shinty club and the local curling club.13

Left: The Marquis of Lorne, first honorary president of Rangers, before his wedding to Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria. Right: One of the first members’ cards, from season 1874–1875. The names of all the founding fathers are to the fore, along with the patron, The Most Noble The Marquis of Lorne.

It is unlikely Lorne ever watched Rangers play in the early years – there is no record of it – as his life in London and Argyll was demanding, not to mention the fact that in 1878 he left British shores to become Governor General of Canada. He and Louise made a massive contribution to Canadian life at the time and their patronage of the arts and letters was underlined with the establishment of institutions such as the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the National Gallery of Canada. Lorne and Louise returned to Britain in 1883 and he became ninth Duke of Argyll following the death of his father in April 1900. Lorne died of pneumonia on the Isle of Wight in May 1914, aged 68 and was buried at Kilmun – not the first with a Rangers connection to be buried at that peaceful graveyard by the shores of the Holy Loch. Louise, his wife of 43 years, lived out the rest of her long life at Rosneath Castle, although she died at Kensington Palace in 1939, aged 91. In her latter years she thought nothing of using her royal status to walk into any house in Rosneath unannounced to ensure all within were well. She shared the village for many years with Moses McNeil, who lived out his latter years in the close-knit community where he had been raised for part of his younger life. History has not recorded if they were ever on speaking terms. They may have led two very different existences, but they could claim without fear of contradiction membership of special institutions that still mean so much to so many.

It is to the credit of the founding fathers that they quickly attracted supporters of means and substance, not just financially, that would give their infant club the best chance of survival beyond a few short years – it was a feat few teams would manage in those chaotic times of the game’s development. In addition to the Marquis of Lorne, the McNeils also used their family connections at Gare Loch to secure the backing of the two most important families in the Glasgow retail trade, who built a palace for high-class shoppers, that is still in use in the city in the 21st century.

John McNeil, father of Moses, was a master gardener at Belmore House which still stands as part of the Faslane Naval Base. In 1856, within 12 months of the birth of Moses, the house was sold by corn merchant John Honeyman to a family of impeccable merchant class who would, with one small gesture, have Rangers off and running 16 years later. The McDonald family had been significant players in the Glasgow retail industry since 1826 when John McDonald, a tailor from Vale of Leven, joined forces with Robertson Buchanan Stewart, a soldier from Rothesay. Their company, Stewart and McDonald, would become such giants of the industry that by 1866 it was turning over a colossal £1 million a year.

Stewart and McDonald opened a wholesale drapery business in the upstairs of a tenement building at No. 5 Buchanan Street, taking a bold risk on the expansion of the city centre westwards from its main thoroughfare on Argyle Street. It was a calculated gamble that paid off within three years when the Argyll Arcade, a glass-covered thoroughfare of jewellers and upper-class outfitters, which retains much of its elegance to this day, was opened and lured more and more shoppers to an area of the town that had hitherto been under-developed for the fashionistas of the age. Stewart and McDonald expanded to meet the demand from the growing population and by 1866 it occupied a massive 4,000 square yards and its huge warehouses dominated Argyle Street, Buchanan Street and Mitchell Street. The first Hugh Fraser was a lace buyer to the company and rose to become a manager in 1849. A series of buyouts and mergers over the next 100 years finally led to it becoming known as House of Fraser. The current Fraser’s department store on the west side of Buchanan Street still occupies the building that was first constructed for Stewart and McDonald.

John McDonald died in May 1860 aged just 51 and the debt of gratitude Rangers owe is to his sons, Alexander or, most probably, John junior. Alexander had been made a director of Stewart and McDonald in 1859 but passed away in his prime, dying of consumption during a tour of the Upper Nile in March 1869, aged only 31. The family fortune, including Belmore, passed in trust to John, then aged only 18, but the McDonald family would help develop a football legacy with one act of kindness, revealed by John Allan in his early history of Rangers. He wrote: ‘To William (McNeil) there fell the rare gift of a football from the son of a gentleman by whom his father was employed in the Gareloch. The generous donor was a Mr McDonald of the firm Stewart and McDonald, in Buchanan Street.’14 It was the same ball Willie would stuff under his arm before storming off in a huff at the prospect of being refused permission to play for the newly formed Rangers, telling his brother and their pals: ‘If you can’t have me, you can’t have my ball.’15 He was not allowed to wander far, as Moses admitted in later years: ‘Willie was the proud possessor of a ball so, although he was the veteran of the little company, it was indispensable that he should be a member of our team.’16