The Genius (14 page)

Authors: Jesse Kellerman

Tags: #Psychological fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Art galleries; Commercial, #New York (N.Y.), #General, #Psychological, #Suspense, #Drawing - Psychological aspects, #Psychological aspects, #Thrillers, #Mystery fiction, #Fiction, #Drawing

As soon as I saw the letter, I called McGrath.

He said, “You remember how to get here?”

This time I did some advance planning and hired a car and driver for the following day. It took me the better part of an afternoon to unmount and pack up the journals, which I took along with photocopies of the Cherubs and the newspaper portraits that I’d dug up. I couldn’t think of anything else that would help except the letter itself, and that I had in a large Ziploc bag, imagining that McGrath would whip out a fingerprint kit and plug the information into a database yielding Cracke’s location and life history.

Instead he just chuckled. He put the bag with the letter on the table and stared at its tight command: STOP. After a few moments he said, “I don’t know why I’m still reading this. I’m pretty sure I know what’s going to happen next.”

“What do I do?”

“Do?”

“With that.”

“Well, you could take it to the police.”

“You are the police.”

“Ex,” he said. “Sure. You can take it to the police if you want. I’ll call ahead for you, if you’d like. Let me save you some time: they’ll won’t be able to do a thing. You don’t know who he is, you don’t really know that he wrote it, and even if you had those two nailed, he hasn’t broken the law.” He smiled like a death’s-head. “Anybody can send a letter like this, it’s in the Constitution.”

“Then why am I here?”

“You tell me.”

“You implied that you had something to offer me,” I said.

“I did?”

“You asked if I remembered how to get here.”

“So I did,” he said.

I waited. “And?”

“And, well. Now that you’re here, I’m just as confused as you are.”

We both looked at the page.

The same tendency toward repetition that had previously fascinated me now seemed repellent; where before I saw passion I now read malice. Art or threat? Victor Cracke’s letter could very well go up on my gallery wall. Were I so inclined, I could probably turn it around to Kevin Hollister for a nice profit.

“I’d hold on to it,” said McGrath. “In case anything gets more serious, you want to have it on file, to show the cops.”

I said, “Plus you never know what it might be worth one day.”

McGrath smiled. “Now, what about that drawing.”

I handed the photocopy of the Cherubs to McGrath. While he studied it I noticed that the number of pill bottles on the dining room table seemed to have grown in the space of a week. McGrath, as well, had changed: he’d lost weight, and his skin had acquired an unhealthy sheen. I could make out the prescriptions on some of the bottles, but not knowing anything about medicine, I couldn’t draw any conclusions except that he seemed to be in a lot of pain.

“That’s Henry Strong.” He lightly touched the Cherubs. “That’s Elton LaRae.”

“I know,” I said. I took out the photocopies of the microfiche and showed him the pictures. “This is where he got them from.” I didn’t mention my misgivings about this theory, but McGrath leapt on me right away.

“I have no idea,” I admitted when he asked how Cracke would be able to connect Henry Strong with the others.

“We also have to ask ourselves why he chose to draw these particular people, out of everyone in the paper.”

“I thought about that,” I said. “You have to bear in mind that he drew literally thousands and thousands of faces. There could be all sorts of real people in his works. The presence of these people only proves that he was thorough.”

“But this is panel number one,” said McGrath. “They were important.”

“That’s subjective,” I said.

“Who said I was objective?”

It felt bizarre arguing with him: me, the art dealer, pressing for a clearer standard of truth; him, the policeman, claiming his critical faculties were sharp enough to draw inferences about the intent of the artist. Strange, too, that he had anticipated my asking certain questions. I felt a weird sort of mental synergy, and I think he did, too, because we stopped talking then and sat looking at the page.

“I’ll tell you what,” he said, “he could really draw.”

I nodded.

He put his finger on another of the Cherubs. “Alex Jendrzejewski. Ten years old. His mother sends him down to the store before dinnertime to buy some groceries. We find a bottle of milk cracked open on the corner of Forty-fourth and Newtown. It’d snowed that afternoon, so we picked up some tire tracks, as well as a footprint. No witnesses.” He rubbed his head. “That was end of January 1967, and this time the papers picked up the story and ran with it. ‘Are Your Children Safe?’ and that sort of jazz. He must’ve got spooked, because he didn’t do anything for a long time. Or maybe he wasn’t a cold-weather sort of guy.”

“There are fewer children out on the street in the winter.”

“You’re right. That could be it, too.” He pointed to another Cherub. “Abie Kahn, I told you about him, he was the fifth.”

“No witnesses.”

“Well, that’s what I thought. I was rereading the case file, and I saw that there was someone we talked to, a neighborhood type, one of these women who sit out on their porch all day long. She remembered seeing a strange car go past.”

“That’s it?”

He nodded. “She told us she knew what everyone drove. Like she made a point of knowing. And this car didn’t fit in the neighborhood.”

Had Victor owned a car? I didn’t think so, and told McGrath.

“That in itself doesn’t mean anything. He could have stolen one.”

“I can’t see him being capable of breaking into a car.”

“You can’t see him at all. You don’t know anything about him. Can you see him being capable of this?” He gestured to the Cherubs.

I said nothing. I knew some of what McGrath was telling me about the victims; I had read the articles in the paper. The critical difference between seeing a story in print and getting it from him directly was the fatherly devotion that came through as he talked.

“That kid, LaRae—him I felt bad for. I felt bad for all of them, but this kid… He’s a solitary type, likes to take long walks by himself. I don’t think he had too many friends. You can tell from the way he’s smiling that he doesn’t like to have his picture taken. He was the oldest of the bunch, twelve, but small for his age. He had a rough time at school because of his size, and because he’s got a single mother, black. You can imagine the kind of ribbing the poor kid took. And the mother, God, it broke my goddamned heart. White husband runs off, leaving her with the kid. And then

he

ends up dead. Oh, brother. She looked like I tore her heart out with my bare hands.”

Silence.

“You want a joint?” he asked.

I looked at him.

“Cause I’m having one.” With difficulty, he rose and shuffled into the kitchen. I heard him open a drawer, and I craned over the table to look. I’ve seen thousands of joints rolled in my day, but never by a policeman, and never with such diligence. He finished, resealed the bag, and returned to the dining room.

“This works better than anything they give me,” he said, lighting up.

I then asked a supremely silly question. “Do you have a prescription?”

His laughter sent out little billows of smoke. “This ain’t California, buddy.”

Based on the poster in the front window and bin Laden wanted sign, I had assumed that McGrath wasn’t especially liberal. I asked his political affiliation.

“Libertarian,” he said. “Drives my daughter crazy.”

“She’s… ?”

“Bloodiest heart you’ll ever find.” He inhaled, and said in a choked voice, “Doesn’t stop her from putting people away. Her boyfriend used to bust her ass about that.”

I should have been less disappointed than I was to hear that Samantha was already attached. I had spoken to her for a grand total of—what? Perhaps twenty minutes. Nevertheless I couldn’t resist reaching over to take the joint from McGrath.

He watched me take a big hit. “That’s an offense punishable by law,” he said.

I made as if to throw the joint away, but he snatched it back.

“I’m dying,” he said. “What’s your excuse?”

NEXT WE CHECKED THE JOURNALS. As I opened them up, I said that unless the weather or Cracke’s dietary habits had some bearing on the case, I didn’t see the point. McGrath agreed, but all the same he wanted to look at the dates of the murders.

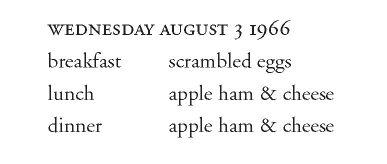

Henry Strong had gone missing on the Fourth of July 1966. The weather journal entry for that day read

“Sounds about right,” said McGrath. “Queens in July.”

The next few days proved equally uninteresting.

“Are these numbers accurate?” I asked.

“How the hell would I know?” He paged through the journal. “I’m not getting very much out of this, are you?”

I shook my head.

“What about the one with the food?”

“This is a waste of time,” I said.

“Probably,” he said. “Let’s look at Eddie Cardinale.”

“You know what I’d like to know,” he said. “How the guy could eat the same damn thing day in and day out. That’s the real mystery.”