The Genius and the Goddess (16 page)

Read The Genius and the Goddess Online

Authors: Jeffrey Meyers

14. Marilyn, signed studio photo, 1956

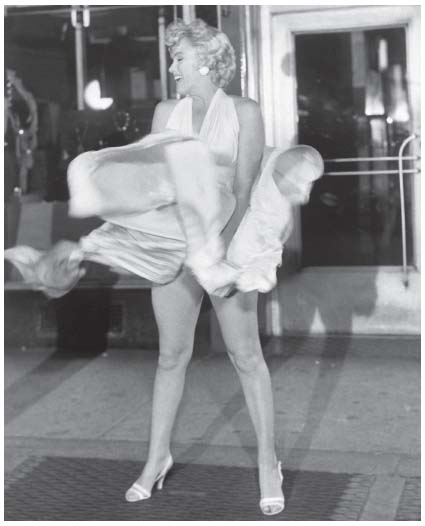

15. Marilyn in

The Seven Year Itch

, 1955

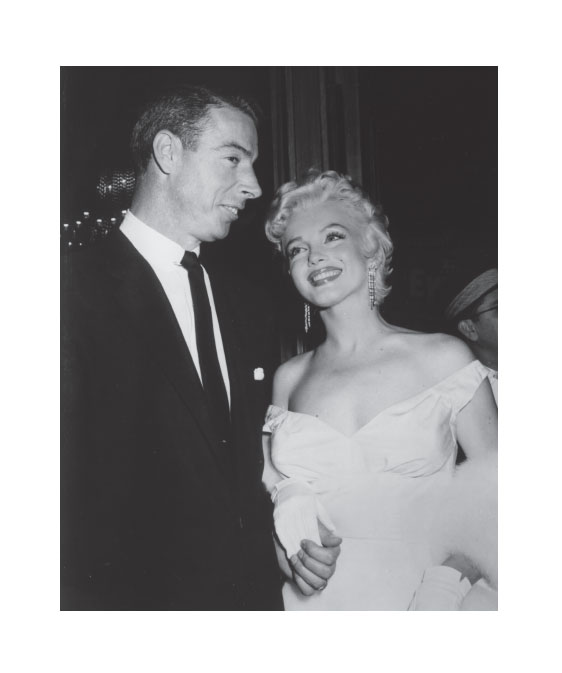

16. Marilyn and DiMaggio

at premiere of

The Seven

Year Itch

, June 1955

Secret Courtship

(1954–1955)

I

Toward the end of 1954, after her failed marriage to DiMaggio,

Marilyn went to New York to study with Lee Strasberg at the

Actors Studio, and to resume her liaison with Miller. She moved from

her native city and the fake glamor of the unintellectual movie industry,

into a completely different culture – literary, theatrical and highbrow.

She understood Hollywood and had made her career there; now,

financially and emotionally dependent on Milton and Amy Greene,

she was starting again. As she tried to enter this unfamiliar society,

she made daily visits to a psychoanalyst and took classes with a famous

teacher to improve her acting skills. She was lonely until she met

Miller, who belonged to this world and helped – as companion, guide

and teacher – to bring her into it. He, in turn, was fascinated by

Marilyn's extraordinary power to attract and interest eminent writers.

It was difficult for her to contact him, since he worked at home.

The photographer Sam Shaw introduced her to Miller's college friend,

Norman Rosten, who told Miller she was in town, and they finally

met at one of Strasberg's theatrical parties in June 1955. Miller, meanwhile,

still trying to stay out of the emotional vortex and sustain a

marriage destroyed by "mutual intolerance," was torn between desire

and guilt: "I no longer knew what I wanted – certainly not the end

of my marriage, but the thought of putting Marilyn out of my life

was unbearable." So he renewed his secret courtship in a series of

romantic settings: the Greenes' country house in Weston, Connecticut;

the Rostens' summer cottage in Port Jefferson, Long Island; the

Strasbergs' summer place on Fire Island; and Marilyn's posh suite high

up in the Waldorf Tower.

Mary Miller's reaction to her husband's relationship with Marilyn

helped propel him into his eventual marriage to Monroe. Mary had

renounced her Catholic faith, shared Miller's left-wing politics, and

tried psychoanalysis in an attempt to understand and perhaps solve

their problems. In October 1955 she discovered that Miller was

having an affair. Their son Robert, then eight years old, later remembered

that there was a lot of anger and tension in the air and that

he tried in vain to play the peacemaker. Mary, who'd made many

sacrifices in the early years of their marriage while her husband

struggled for success, was both wounded by his infidelity and furious

about his betrayal. She threw him out of the house; and he moved

into the Chelsea Hotel, a refuge for bohemians and artists, on West

23rd Street.

Kazan, sympathizing with Miller, described the tense situation that

followed: "Month after month he'd begged Mary to take him back,

but she couldn't bring herself to forgive her husband. . . . He'd been

doing his best to hold their marriage together, but according to him,

his wife was behaving in a bitterly vengeful manner." Miller's sister,

Joan Copeland, said the break-up of his marriage came as a big

surprise:

I would hear snippets of rumors but I'd just pooh-pooh it because

when you're in that position of celebrity, people are going to

say and write all sorts of terrible things about you. So I was

guarded against any kind of malicious rumor. I just didn't believe

it and I didn't ask Mary or Arthur about it. But Marilyn would

search me out at the [Actors] Studio and we'd have lunch, talk

about scenes. I guess she was trying to curry my favor, or maybe

she just liked me.

1

Miller finally decided to get a divorce in Nevada, which was much

easier to obtain than in New York. In order to qualify, he had to

reside in the state for six weeks.

Saul Bellow was already living out

there, divorcing his first wife in order to marry his second. On March

15, 1956, at the suggestion of a mutual friend, Pascal Covici, Miller

wrote to Bellow. He asked for advice and, in a bit of one-upmanship,

expressed pride in possessing the woman whom millions of other

men longed for:

Congratulations. Pat Covici tells me you are to be married. That

is quite often a good idea.

I am going out there around the end of the month to spend

the fated six weeks and have no idea where to live. I have a

problem, however, of slightly unusual proportions. From time to

time there will be a visitor who is very dear to me, but who is

unfortunately recognizable by approximately a hundred million

people, give or take three or four. She has all sorts of wigs, can

affect a limp, sunglasses, bulky coats, etc., but if it is possible I

want to find a place, perhaps a bungalow or something like,

where there are not likely to be crowds looking in through the

windows. Do you know of any such place?

Bellow was then living in one of two isolated cabins on Sutcliffe

Star Route, on the western shore of Pyramid Lake, and in due course

Miller rented the one next door. Both the cabins and the lake, about

forty miles north of Reno, were on the Paiute Indian reservation. In

those days there was almost no one else around, and the lunar landscape

seemed just the way it was when the world was first created.

Ten years earlier,

Edmund Wilson had stayed in Minden, south of

Reno, while waiting for his divorce. He'd amused himself in that

debauched and dehydrated part of the world by exploring the desert,

lakes and wildflowers, walking around the pleasant town square and

doing a bit of gambling. In a letter to Vladimir Nabokov, he described

it as "a queer and desolate country – less romantic than prehistoric

and spooky."

A motel near the cabins had once put up people waiting for a

divorce, but now housed only the owners, who had the only pay

phone between the cabins and Reno. When a call came, they'd drive

over to summon one of the self-absorbed writers to the outside world.

The companionable highlight of the week was the drive to Reno in

Bellow's Chevy to do their laundry and buy groceries for their spartan

meals. Bellow stayed longer than the required six weeks, with his new

bride

Sondra Tschacbasov, in order to continue work on his novel

Henderson the Rain King

. (His second marriage lasted only three years,

and he would satirize his ex-wife as Madeleine in

Herzog

.)

In a letter of May 12, 1956 to his college teacher Kenneth Rowe,

Miller emphasized his strange isolation: "There is no living soul nor

tree nor shrub above the height of the sagebrush. I am not counting

my neighbors, Saul Bellow, the novelist, and his wife, because they

are on my side against the lunar emptiness around us." Miller recalled

that Bellow, in a Reichian catharsis, liked to scream into the landscape:

"Saul would sometimes spend half an hour up behind a hill a

half-mile from the cottages emptying his lungs roaring at the stillness,

an exercise in self-contact."

Sondra Bellow – who rode horses from the dude ranch into the

hills behind the house – recalled that the two writers did not, as one

might expect, have intense and stimulating conversations:

Miller came out perhaps in mid- or late May for his six-week

residency. We overlapped maybe three weeks at most, since we left

Nevada the beginning of June. The conversations with Miller at

that time were less than fascinating, at least from a literary point

of view. He talked a bit about his marriage and how difficult it

was to make the decision to get a divorce. But his attention was

almost totally focused on Marilyn Monroe. He talked non-stop

about her – her career, her beauty, her talent, even her perfect feet.

He showed us the now famous photos by Milton Greene – all

quite enlightening since neither Mr. Bellow nor I had ever even

heard of her before this. To my disappointment, Monroe was filming

Bus Stop

at the time, and never did get to visit Miller in Nevada.

I actually spent more time with Miller than did Bellow, who

dedicated much of his day to writing, and believe me, conversation

was not at all literary, as you can surmise from the above.

Miller occupied himself mornings in his cabin, and also spent a

huge amount of time talking (presumably to Monroe) on the

only available telephone in the area. This was a pay telephone

booth a half mile away on a dirt road used primarily – and

rarely – by hunters traveling north. He and I would spend some

afternoons together – sightseeing, or going into Reno, or hiking

around Pyramid Lake. He generally had dinner with us, during

which he repeated all the Marilyn stories he had already told

me during the day.

I believe the "bond" between [Bellow and Miller] at this time

had much less to do with their being writers, and more to do

with their being in somewhat the same place in terms of ending

a long-term marriage and starting anew with a much younger

woman. I never heard a single literary exchange between them.

They sort of metaphorically circled each other, and pawed

the ground. You just knew it from their body language. They

told jokes – especially shaggy dog stories with a Yiddish flavor

– and gossiped rather than have significant conversation.

Miller had all those Hollywood connections that Bellow would

have felt was "selling out." But it was fun to hear his stories. He

also thought Miller was not a real intellectual (like the

Partisan

Review

crowd). Bellow came from a rabbinical intellectual tradition

and Miller's father didn't read or write but had his wife

help him.

Miller also was soon to be testifying in Washington before

the House Un-American Activities Committee, but there was

little substantive discussion about this as well, mostly because

Miller was caught up in the Monroe romance, and also, in part,

because Bellow and Miller had very different political philosophies.

[Bellow was a Trotskyite at the time and Miller was not.]

2

Miller and Bellow were both born in 1915 to Jewish immigrant

parents. Bellow had reviewed Miller's novel,

Focus

(1945), in the

New

Republic

and thought the sudden transformation of the main character

from Jew-hater to a man who accepts his enforced identity as

a Jew was unconvincing: "The whole thing is thrust on him. . . . Mr.

Newman's heroism has been clipped to his lapel. . . . If only he had

had more substance to begin with." Miller accepted the criticism and

didn't hold it against him. He published his short story, "Please Don't

Kill Anything," in Bellow's little magazine, the

Noble Savage

, and later

commended Bellow's work: "I like everything he writes. He still has

a joy in writing. . . . He is a genius. . . . He's kind of a psychic journalist

– which is invaluable. He's just simply interesting. . . . His work

seems necessary, which is high praise. It seems to mark the moment."

Bellow won the Nobel Prize, Miller did not, which may account for

his rather patronizing tone.

Miller didn't spend all his time with his companions at Pyramid

Lake. Marilyn, working on

Bus Stop

, never visited him in Nevada. But

Miller, risking the loss of continuous residence that was required for

his divorce, secretly slipped into Los Angeles for a series of romantic

encounters on Sunset Boulevard. (The FBI, tracking Miller's movements,

knew he was leaving Nevada to see Marilyn.) Amy Greene

recalled that "Arthur would come out on weekends . . . they'd lock

themselves up at the Chateau Marmont Hotel. He would arrive on

Friday, she would go to the Marmont that night, come back to us

Sunday night and she would be a mess on Monday. He was still

married and she would be upset because she couldn't show this man

off to everyone because he still had a wife and two children in

Brooklyn."

On June 2, after Bellow's departure, Miller told him that conditions

had radically changed at Pyramid Lake and described the

intrusive publicity that would both excite and plague them throughout

their marriage. Marilyn was protected by the studio, which controlled

access by the press. But Miller, though a famous playwright, had never

experienced such aggressive attention: "The front page of the [

New

York Daily

]

News

has us about to be married, and me 'readying' my

divorce here. All hell breaks loose. The [imported] phones all around

never stop ringing. Television trucks – (as I live!) – drive up, cameras

grinding, screams, yells – I say nothing, give them some pictures, retire

into the cabin. They finally go away."

3

Miller, not Mary, was granted a divorce on the grounds of her

extreme mental cruelty, but she exacted harsh terms and made him

pay dearly for his betrayal. She "was awarded custody of their two

children, Jane (b. 1944) and Robert (b. 1947), child support payments

(including rises in the cost of living), the house they had recently

bought on Willow Street in Brooklyn Heights, plus a percentage of

all his future earnings until she remarried (she never did)."He managed

to keep their weekend house in Connecticut, but was responsible for

all her legal costs as well as his own. He felt guilty and was willing

to pay for his mistakes in order to marry Marilyn. Most of his friends

never saw Mary again. She just disappeared and seemed to be wiped

out of existence. During our conversation, Mary refused to discuss

her contribution to Miller's early success. I told her that she'd been

repeatedly characterized as a dull, boring, sexless wife who'd been

cast off when someone better turned up. Instead of defending herself,

she self-effacingly said: "Maybe I was."

4

Many men had slept with Marilyn, both before and after she'd become

a famous sex symbol, and thought nothing of abandoning her the

following day, but Miller was devoted to her and always treated her

with respect. He perceived her innocence beneath the sexy image,

found her waif-like quality appealing and instinctively felt sorry for

her. He thought she was opaque and mysterious – not at all the happy,

dizzy blonde – and wanted to rescue her from her profound misery.

At the same time, he saw her talent and realized he could write material

for her and about her. She was a personal and artistic challenge,

a tragic muse. She was also fascinating because she was so extraordinarily

desirable in the eyes of the world. Miller was famous, but

Marilyn was a phenomenon.