The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ (11 page)

Read The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ Online

Authors: David Shenk

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

A reporter somehow picked up the story and published it in the

Minneapolis Tribune

, which caught the attention of University of Minnesota psychologist Thomas Bouchard. Fascinated, Bouchard invited the Jims to campus for a formal investigation.

“I thought we were going to do a single case study,” Bouchard later recalled

. “[But then] we got quite a bit of publicity.

People

magazine ran a story. They were on the Johnny Carson show. They really fascinated everybody. And so I wrote a grant proposal.” The grant money poured in, and more separated twins came to the surface. Within a year, Bouchard and colleagues had studied fifteen other pairs; similar research blossomed around the world.

It was one of Charles Darwin’s great puzzlements.

“Nothing seems to me more curious,” he once wrote, “than the similarity and dissimilarity of twins

.” How could some identical twins be so alike and others turn out so different? In separated twins, research psychologists like Bouchard thought they had a unique opportunity to find out, a Darwinist’s dream shot at distinguishing nature from nurture. Their method was to compare the ratio of similarities/differences in separated identical twins with the same ratio in separated fraternal twins.

Since identical twins were thought to share 100 percent of their DNA

and fraternal twins share, on average, 50 percent of their genetic material (like any ordinary siblings), comparing these two unusual groups allowed for a very tidy statistical calculation.

The end product was an arcane statistical estimate that researchers unfortunately chose to call “heritability.”

Heritability isn’t at all what it sounds like. The word does not mean anything remotely close to the word “inherited.” As a result of this dreadfully irresponsible word choice, science journalists and the rest of us have been given a profound misimpression of twin studies and what they’ve proven.

Journalists were understandably blown away when Bouchard and colleagues published data that seemed to demonstrate that genes were responsible for roughly

:

60 percent of intelligence

60 percent of personality

40 to 66 percent of motor skills

21 percent of creativity

Such striking statistics, combined with the compelling stories of the Jims and other sets of twins, had a tidal-wave effect on the media and other scientists. Tragically (predictably), “heritable” and “inherited” quickly became interchangeable in the popular lexicon, which led to absurdly reductionist statements like these:

“Since personality is heritable …” (

New York Times

)

“In some significant ways … criminals are born, not made.” (Associated Press)

“Men’s Fidelity Controlled by ‘Cheating Genetics’” (Drudge Report)

In his 1997 book

Twins

, the award-winning journalist Lawrence Wright extolled what he and others saw as Bouchard’s breathtaking scientific achievement. Wright went so far as to declare that Francis Galton and the genetic determinists had been right all along:

Alas, Wright and other well-meaning journalists relying on Bouchard got it very wrong. Not understanding the true meaning of “heritability,” nor the importance of gene-environment interaction, they radically overstated the direct influence of genes. To be sure, twin studies did—unequivocally—prove that genes are an important and constant influence. Around the world, researchers were able to replicate the basic finding that identical twins had a higher concordance than fraternal twins of intellect, character, and just about everything else. This certainly helped put to rest old arguments from the past that every individual is a blank slate completely shaped by his or her environment.

Blank Slate is dead. Genetic differences do matter.

But the nature of that genetic influence is easily—and perilously—misinterpreted. If we are to take the word “heritability” at face value, genetic influence is a powerful direct force that leaves individuals rather little wiggle room. Through the lens of this word, twin studies reveal that intelligence is 60 percent “heritable,” which implies that 60 percent of each person’s intelligence comes preset from genes while the remaining 40 percent gets shaped by the environment. This appears to prove that our genes control much of our intelligence; there’s no escaping it.

In fact, that’s not what these studies are saying at all.

Instead, twin studies report, on average, a statistically detectable genetic influence of 60 percent. Some studies report more, some a lot less. In 2003, examining only poor families, University of Virginia psychologist Eric

Turkheimer found that intelligence was not 60 percent heritable, nor 40 percent, nor 20 percent, but

near

0 percent

—demonstrating once and for all that there is no set portion of genetic influence on intelligence. “These findings,” wrote Turkheimer, “suggest that

a model of [genes plus environment] is too simple

for the dynamic interaction of genes and real-world environments during development.”

How could the number vary so much from group to group? This is how statistics work. Every group is different; every heritability study is a snapshot from a specific time and place, and reflects only the limited data being measured (and how it is measured).

More important, though, is that all of these numbers pertain

only

to groups—not to individuals.

Heritability, explains author Matt Ridley, “is a population average, meaningless for any individual person

: you cannot say that Hermia has more heritable intelligence than Helena. When somebody says that heritability of height is 90 percent, he does not and cannot mean that 90 percent of my inches come from genes and 10 percent from my food. He means that variation in a particular sample is attributable to 90 percent genes and 10 percent environment. There is no heritability in height for the individual.”

This distinction between group and individual is night and day. No marathon runner would calculate her own race time by averaging the race times of ten thousand other runners; knowing the average lifespan doesn’t tell me how long my life will be; no one can know how many kids you will have based on the national average. Averages are averages—they are very useful in some ways and utterly useless in others. It’s useful to know that genes matter, but it’s just as important to realize that twin studies tell us nothing about you and your individual potential. No group average will ever offer any guidance about individual capability.

In other words, there’s nothing wrong with the twin studies themselves. What’s wrong is associating them with the word “heritability,” which, as Patrick Bateson says, conveys “the extraordinary assumption that genetic and environmental influences are independent of one another and do not interact. That assumption is clearly wrong.” In the end, by parroting a strict “nature vs. nurture” sensibility, heritability estimates are statistical phantoms; they detect something in populations that simply does not exist in actual biology. It’s as if someone tried to determine what percentage of the brilliance of

King Lear

comes from adjectives. Just because there are fancy methods available for inferring distinct numbers doesn’t mean that those numbers have the meaning that some would wish for.

So what about Darwin’s essential question: How could some identical twins be so alike and others turn out so different? Leaving behind the misconceptions of heritability, developmental biologists and psychologists suggest the following real-world considerations for why twins turn out the way they do:

1.

Early shared GxE

. Identical twins share a wide collection of similarities not just because they share the same genes, but because they share the same genes

and

early environments—hence, the same gene-environment interactions throughout gestation.

2.

Shared cultural circumstances

. In identical-twin comparisons, shared biology always grabs all the attention. Inevitably overlooked is the vast number of shared cultural traits: same age, same sex, same ethnicity, and, in most cases, a raft of other shared (or very similar) social, economic, and cultural experiences.

“All of these factors work towards increasing the resemblance of reared-apart twins,” explains psychologist Jay Joseph

.

Just how powerful are these shared cultural influences?

To test the influence of just a few of them, psychologist

W.J. Wyatt assembled fifty college students completely unrelated and unknown to one another and then placed them in random pairings purely on the basis of age and sex. Among the twenty-five pairs, one pair showed a remarkable collection of similarities: both Baptists, both pursuing nursing careers, both passionate about volleyball and tennis, both favored English and math, both detested shorthand, and both preferred to vacation at historical places. The point from this very limited study is not to draw definitive conclusions about specific environmental influences, but to draw attention to the power of unseen similar circumstances.

3.

Hidden dissimilarities

. Statisticians call it “the multiple-end-point problem”: the seductive trap of selectively picking data that fit a certain thesis, while conveniently discarding the rest. For every tiny similarity between the Jim twins, there were thousands of tiny (but unmentioned) dissimilarities. “There are endless possibilities for doing bad statistical inferences,” says Stanford statistician Persi Diaconis. “You get to pick which features you want to resonate to. When you look at your mom, you might say, ‘I’m exactly the opposite.’ Someone else might say, ‘Hmm.’”

New York Times

science writer Natalie Angier adds

, “What the public doesn’t hear of are the many discrepancies between the twins. I know of two cases in which television producers tried to do documentaries about identical twins reared apart but then found the twins so distinctive in personal style—one talky and outgoing, the other shy and insecure—that the shows collapsed of their own unpersuasiveness.”

4.

Coordination and exaggeration

. All twins feel a close bond with each other, and while child twins growing up together might often cling to their differences, reunited adult twins understandably revel in their similarities. Researchers try to guard against any purposeful or unwitting coordination, but in her 1981 book

Identical Twins Reared Apart

, Susan Farber reviewed 121 cases of twins described by researchers as “separated at birth” or “reared apart.” Only three of those pairs had actually been separated shortly after birth

and

studied at their first reunion. At the University of Minnesota, the average age of separated twins studied turned out to be forty, while their average years spent apart was thirty—leaving an average of ten years of contact prior to research interviews.

Considering all this, was it really so shocking that Jim Lewis and Jim Springer, two thirty-nine-year-old men who shared a womb for nine months and a month more in the same hospital room,

and

were raised in working-class towns seventy miles apart (by parents with tastes similar enough to name their kids Jim and Larry), would end up preferring the same beer, same cigarettes, same car, same hobbies, and have some of the same habits

? (

Lest anyone think they were living perfectly parallel lives

, it’s also worth noting a few of their differences: One of the Jims was married a third time. They wore their hair very differently. One was much more verbally articulate than the other …)

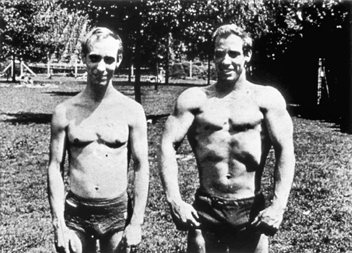

By the same token, should it really surprise anyone to see the picture of identical twins below?

Otto (left) and Ewald (right)

, age twenty-three, had trained intensively for different athletic advantages—Otto as a long-distance runner, and Ewald for strength events.