The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 (25 page)

Read The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 Online

Authors: Robert Gellately

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Law, #Criminal Law, #Law Enforcement, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #European, #Specific Topics, #Social Sciences, #Reference, #Sociology, #Race Relations, #Discrimination & Racism

Criticism of Mann's work must be tempered, of course, by the fact that it remained incomplete at his death in 1981. Moreover, his pioneering effort represents an extremely important contribution to the study of the routine operation of the Gestapo, and it is most fortunate that his manuscripts and sketches have recently been published. It is still the case that readers need to be made aware of a limitation of his analysis, a consequence of his decision to eliminate those eleven categories of cards mentioned above. At issue is not so much that he decided not to deal with 1,230 cards, but the kind of card, and hence the case-files, that were thereby excluded from his analysis. The following specific categories of cards were left out: 'Germans returning from abroad, foreigners, Jews, emigrants, foreign workers, prisoners of war, military espionage, economic sabotage, separatism, foreign legionnaires, and racially foreign minorities'. Mann's explanation for excluding these groups is given in a footnote. He observed that these cards pertained primarily to foreigners, who, like `Jewish fellow citizens were subject to different legal norms', and he claimed that inclusion of such persons `would have com

plicated the investigation further'."

These comments seem evasive; they are hardly convincing arguments to support the decision to exclude these groups in a study devoted to everyday life in Nazi Germany. Had Mann lived longer, he might have reorientated his investigation to include these groups as well. However, the fact remains that their exclusion may have had important consequences for the results of his study. Because his quantitative analysis of the Gestapo's operations excludes explicit consideration of most case-files in which the police were faced with enforcing policy on 'racially foreign' groups in Germany, there is a high probability that it underestimates the extent of popular participation-through the provision of information-in the functioning of the Gestapo. To arrive at conclusive findings, of course, one would have to examine in detail those files excluded by Mann, but until that is done one may make an initial judgement on the basis of an examination of Gestapo dossiers from Wurzburg, specifically of the kind excluded in Mann's investigation. One is bound to conclude from such an examination that, had Mann taken his sample from all of the 5,000 Gestapo files (rather than the 3,770) in the 'local card-file Dusseldorf, then the percentage of cases which began with a denunciation would in all probability have been higher than indicated in Table 2.

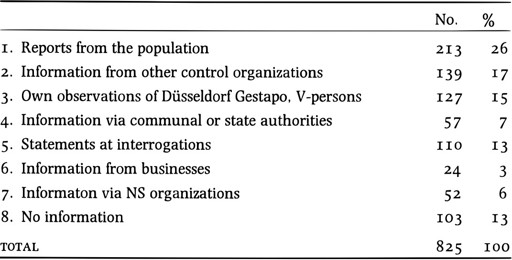

TABLE 2.-Causes of the Initiation of a Proceeding with the Dusseldorf Gestapo (1933-1944)

Source: R. Mann, Protest and Kontrolle, 292.

Evidence in Wurzburg and elsewhere suggests that in all likelihood most of his categories contain instances of denunciations, though not all the accusations were lodged directly with the Gestapo. A case could commence when an individual merely dropped a hint sure to be overheard by some official or even a tell-tale neighbour. A classic example of the latter is offered in the story by Rolf Hochhuth, since turned into a film, Eine Liebe in Deutschland.'

8 Beyond that, once in the grasp of the Gestapo, victims could easily incriminate themselves or others in the course of interrogation: and it is clear that on occasion chance played a role in the Gestapo's being made aware of some 'criminal' behaviour or other.

Though care must be taken with quantitative analysis of materials such as Gestapo case-files, especially regarding the sources that led to the opening of a case, it is clear that denunciations from the population were crucial to the functioning of the Gestapo. We know that 26 per cent of all cases began with an identifiable denunciation, and this must be taken as a minimum figure. Many of the other categories in Table 2-such as cases that began with information 'from Nazi organizations', 'other control organizations', 'communal and state authorities'-were also to a large degree dependent upon tips from citizens. With all due caution, it seems justified to suggest that denunciations from the population constituted the single most important cause for the initiation of proceedings of all kinds.

Put another way, these figures indicate that the regime's dreaded enforcer would have been seriously hampered without a considerable degree of public

co-operation. This behaviour has hitherto been largely ignored or not fully understood. To ask whether this is evidence that the public was converted to Nazism, or that the Nazi message had actually become widely acceptedas Mann would have it-is rather misconceived, because co-operation or collaboration was motivated by a whole range of considerations. The question of motives aside, denunciations from the population were the key link in the three-way interaction between the police, people, and policy in Nazi Germany. Popular participation by provision of information was one of the most important factors in making the terror system work. That conclusion suggests rethinking the notion of the Gestapo as an 'instrument of domination': if it was an instrument it was one which was constructed within German society and whose functioning was structurally dependent on the continuing cooperation of German citizens.'9

In support of Mann's quantitative analysis, it should be added, there is abundant corroborating evidence in the eyewitness accounts and in other fragmentary police reports of various kinds from localities elsewhere in Germany.'

For reasons just mentioned, it is clear that his analysis probably underestimates the extent of denunciations precisely because he excluded the kinds of cases where informing from the general population was required-and attained-by the Gestapo.

That the Gestapo was to a large extent a reactive organization, at least when it came to generating cases, may be deduced from Table 2. Its own observations or those of its agents initiated only 15 per cent of all proceedings of the Dusseldorf Gestapo. Information obtained through interrogations, which set in motion 13 per cent of the cases, indicates a more active role in these instances (on which more below), though such undertakings may have been stimulated from a source external to the Gestapo. An important part was also played by the numerous other 'control organizations', including the regular uniformed police, the Kripo, SD, and SS; collectively they were responsible for the initiation of 17 per cent of all cases.

It is possible that some cases were sparked off by a tip from official sources, as when a Gestapo official merely wrote in the file that 'according to a confidentially disclosed report made to me today, it is alleged that the butcher Hans Drat remarked as follows', and so on.21

Still, there would seem no reason

for the dossier to be silent if the tip came from an official or even semi-official body. In all likelihood the source was'from the population', but the full details of this side of the story remain hidden.22

The legal facade surrounding the `seizure of power' no doubt paid dividends in that many law-abiding citizens, out of respect for the legal norms, simply complied and co-operated with the new regime. Because the take-over was not patently illegal, many could choose to ignore its revolutionary character, especially after the radicals were subdued following the purge in June 1934. The stoic acceptance, however, seems to have yielded to more positive attitudes. Hans Bernd Gisevius, a member of the Gestapo in 1933, later recalled that there was a new mood and a widespread (though far from unanimous) positive disposition towards the regime, especially in the efforts to put down the supposed Communist threat.23

What struck him most forcefully was what he called `individual Gleichschaltung', by which he meant a kind of willing self-integration into the new system.24

The terror system had both a formal side-embracing the whole range of institutional arrangements-and an informal side that worked in tandem with those arrangements. Much less has been written about the 'informal' politics in the Nazi dictatorship, but there is much evidence to suggest that existing informal power-structures underwent adjustments as many people began to bring their attitudes on all kinds of issues into line. People may have experienced anxieties, but there were other positive factors at work. Golo Mann remarked that even the massive force and brutality of the Nazi 'seizure of power' were to a considerable extent overlooked: 'it was the feeling that Hitler was historically right which made a large part of the nation ignore the horrors of the Nazi take-over... People were ready for it.'2'

As self-imposed conformity spread, a new social attitude emerged, and at least in some cases transformation took place in a matter of hours, days, or weeks of Hitler's appointment.16

People out of the country for a brief sojourn were astonished on their return.27

Some thought it advisable to make known, without having been asked, that they had no sympathy for the newly proclaimed enemies of the system.28

In October 1933, for example, Agnes Meyer, a cashier in a Wurzburg grocery, turned in a customer who had insisted on getting the 3 pfennigs owed to her in change. She was accused of having said that she was fed up paying

taxes, and especially with laying out money for family allowances. Under questioning by the Gestapo the woman conceded that she might have implied that some people who got such allowances might not have to quibble over small change. Meyer was adamant that an insult to the Fi hrer was intended.29

Similarly, in late 1943, during an air-raid attack in Kitzingen, Johann Muller, a Catholic with two children, overheard Hugo Engelhardt make the following remark: 'Yes, families with many children should be supported, but with the truncheon. And anyone who had more than three children should be castrated!'

3" Engelhardt was reported and brought to trial. Again, this kind of petty tale-telling went beyond any specific injunction of the regime, and, in both these cases, helped reinforce the system's teachings on population policy.

No specific law was ever passed that required citizens to inform on one another, though there was a stipulation in the already existing German criminal code (paragraph 139) that made it a duty to report certain offences one suspected were about to be committed; the law on high treason made a crime out of the failure to communicate to the authorities knowledge of a possible attempt at treason, including threats to Germany's allies, and so on.31

The presidential decree of 21 March 1933 against malicious attacks on the government, and the law of 20 December 1934 against malicious attacks on the state and Party, were both designed to stop gossiping in public places, but also pertained to private remarks which might be repeated later in public. Neither made denunciation a formal duty, or even mentioned the matter, though both seem to have presupposed that the good citizen would inform upon hearing such gossip.32

Clauses in the law were so broadly formulated that the most innocuous criticism of the Party, state, its leading personalities or enactments, could conceivably be a basis for denun

Generally speaking, all authorities of party and state reacted positively to those who brought accusations, regardless of how insignificant the allegation, dubious the source, mixed the motives-even if it concerned an act (an anti-Hitler statement, for example) perpetrated prior to 1933, when such behaviour was not even illegal. Although the flood of denunciations at times inclined various institutions to consider insisting upon signed complaints, verbal and even anonymous tips were usually followed up, and, significantly enough, whether the name of the accuser would (if available) be made public was left to the police. In other words, the extent to which an individual had

recourse to legal defence, even when the charges were false or carelessly laid, was determined by the Gestapo.14

In discussions with Minister of Justice Giirtner in early May 1933, Hitler complained that 'we are living at present in a sea of denunciations and human meanness', when it was not infrequent for one person to condemn another, especially out of economic motives, merely to make capital out of the situation; the resulting worry that one could be turned in for deeds which went back many years was most unfortunate, in that it 'brought monstrous uneasiness in the entire economy'. He added that 'it was not the task of the Third Reich to atone for all the sins' of the Second, so that, especially in the area of economic and tax crime, a line had to be drawn.15

It was clear to local state officials in Bavaria that, by mid-summer 1933, 'many people feared denunciations and their consequences',-a fear, incidentally, that made it very difficult to gauge public attitudes towards the new National Socialist system

.35 Needless to say, Nazi Party types took advantage of the novel situation to settle accounts with old enemies, and 'ordinary' citizens were not above capitalizing on the opportunity to get rid of business competitors through allegations that led to arrest and internment.37