The Ghost in the Machine (40 page)

geometry in curved space, where parallels intersect and straight lines

form loops. Its canon is based on a central axiom, postulate or dogma,

to which the subject is emotionally committed, and from which the rules

of processing reality are derived. The amount of distortion involved in

the processing is a matter of degrees, and an important criterion of

the value of the system. It ranges from the scientist's involuntary

inclination to juggle with data as a mild form of self-deception,

motivated by his commitment to a theory, to the delusional belief-systems

of clinical paranoia. When Einstein made his famous pronouncement 'if the

facts do not fit the theory, then the facts are wrong', he spoke with his

tongue in his cheek; but he nevertheless expressed a profound feeling of

the scientist committed to his theory. As we have seen, an occasional

suspension of strict logic in favour of a temporary indulgence in the

games of the underground is an important factor in scientific and artistic

creativity. But geniuses are rare. And if geniuses sometimes indulge in

these non-Euclidian games where reasoning is guided by emotional bias,

it is an individual bias, a hunch of their own making; whereas the group

mind receives its emotional beliefs ready-made from its leaders or from

its catechism.

to keep the deluded mind happy in its faith is a factor of decisive

importance. Here lies the answer to that ethical relativism which

cynically proclaims that all politicians are corrupt, all ideologies

eyewash, all religion designed to befuddle the masses. The fact that

power corrupts does not mean that all men in power are equally corrupt.

to assert themselves to the detriment of the whole, and then went on to

the pathology of cognitive structures getting out of control: the

idée fixe

of the crank, obsessions running riot, closed systems

centred on some part-truth pretending to represent the whole truth. We now

find similar symptoms on a higher level of the hierarchy, as pathological

manifestations of the group mind. The difference between these two kinds

of mental disorder is the same as that between the primary aggressiveness

of the individual and the secondary aggressiveness derived from his

identification with a social holon. The individual crank, enamoured of

his own pet theory, the patient in the mental home convinced that there

is a sinister conspiracy aimed at his person, are disowned by society;

their obsessions serve some unconscious private purpose. In contrast to

this, the collective delusions of the crowd or group are based, not on

individual deviations but on the individual's tendency to conform. Any

single individual who would today assert that he has made a pact with

the Devil and had intercourse with succubi, would promptly be sent to a

mental home. Yet not so long ago, belief in such things was a matter of

course -- and approved by 'commonsense' in the original meaning of the

term, i.e., consensus of opinion.*

* 'Philosophy of commonsense: accepting primary beliefs of mankind

as ultimate criterion of truth' (The Concise Oxford Dictionary).

primary aggressiveness of individuals, but by their self-transcending

identification with groups whose common denominator is low intelligence

and high emotionality. We now come to the parallel conclusion

that the delusional streak running through history is not due to

individual forms of lunacy, but to the collective delusions generated

by emotion-based belief-systems. We have seen that the cause underlying

these pathological manifestations is the split between reason and belief

-- or more generally, insufficient co-ordination between the emotive and

discriminative faculties of the mind. Our next step will be to inquire

whether we can trace the cause of this faulty co-ordination -- this

disorder in the hierarchy -- to the evolution of the human brain. Should

contemporary neurophysiology, though still in its infancy, be able to

provide some indication of the causes of the trouble, we would have made

a first step towards a frank diagnosis of our predicament and thereby

gain some inkling of the direction in which the search for a remedy

must proceed.

three factors in emotion: nature of the drive, hedonic tone, and the

polarity of the self-assertive and self-transcending tendencies.

equilibrium. Under conditions of stress the self-assertive tendency may

get out of control and manifest itself in aggressive behaviour. However,

on the historical scale, the damages wrought by individual violence for

selfish motives are insignificant compared to the holocausts resulting

from self-transcending devotion to collectively shared belief-systems. It

is derived from primitive identification instead of mature social

integration; it entails the partial surrender of personal responsibility

and produces the quasi-hypnotic phenomena of group-psychology. The

egotism of the social holon feeds on the altruism of its members. The

ubiquitous rituals of human sacrifice at the dawn of civilisation are

early symptoms of the split between reason and emotion-based beliefs,

which produces the delusional streak running through history.

as it were in the air, without any organic foundation . . . Let the

biologists go as far as they can and let us go as far as we can. Some

day the two will meet.

Freud

through human history, it appears highly probable that homo sapiens is a

biological freak, the result of some remarkable mistake in the evolutionary

process. The ancient doctrine of original sin, variants of which occur

independently in the mythologies of divene cultures, could be a reflection

of man's awareness of his own inadequacy, of the intuitive hunch that

somewhere along the line of his ascent something has gone wrong.

and error. There is nothing particularly improbable in the assumption

that man's native equipment, though superior to that of any known animal

species, nevertheless may contain some serious fault in the circuitry of

his most precious and delicate instrument -- the central nervous system.

point; both are stagnant species, but well adapted to their ways of

life, and to call them evolutionary mistakes because they have not

got the brains to write poetry would be the height of hubris. When

the biologist talks of evolutionary mistakes, he means something more

tangible and precise: some obvious deviation from Nature's own standards

of engineering efficiency, a construction fault which deprives an organ

of its survival value -- like the monstrous antlers of the Irish elk. Some

turtles and insects are so top-heavy that if in combat or by misadventure

they fall on their back, they cannot get up again, and starve to death

-- a grotesque error in construction which Kafka turned into a symbol of

the human predicament. But before talking of man, I must discuss briefly

two earlier evolutionary mistakes in brain-building, both of which had

momentous consequences.

more than seven hundred thousand known species, constitute by far the

largest phylum of the animal kingdom. They range from microscopic mites

through centipedes, insects and spiders to ten-foot giant crabs; but

they all have this in common, that

their brains* are built around

their gullets

. In vertebrates, the brain and spinal cord are both

dorsal -- at the back of the alimentary canal. In invertebrates, however,

the main nerve chain runs

ventrally

-- on the belly side of the

animal. The chain terminates in a ganglionic mass

beneath

the

mouth. This is the phylogenetically older part of the brain; whereas

the newer and more sophisticated part of it developed

above

the

mouth, in the vicinity of the eyes or other distance-receptors. Thus

the alimentary tube passes through the midst of the evolving brain-mass,

and this is very bad evolutionary strategy because, if the brain is to

grow and expand, the alimentary tube will be more and more compressed

(see Figure 11). To quote Gaskell's

The Origin of Vertebrates

:

Progress on these lines must result in a crisis, owing to the

inevitable squeezing out of the food-channel by the increasing

nerve-mass. . . . Truly, at the time when vertebrates first appeared,

the direction and progress of variation in the Arthropoda was leading,

owing to the manner in which the brain was pierced by the oesophagus,

to a terrible dilemma -- either the capacity for taking in food

without sufficient intelligence to capture it, or intelligence

sufficient to capture food and no power to consume it. [1]

* In lower forms the ganglionic masses which are precursors of

the brain.

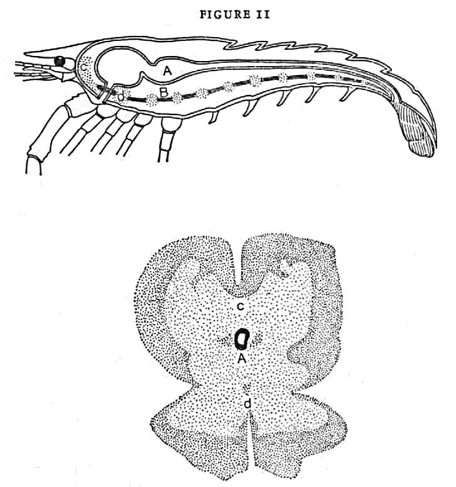

Top: relation between the alimentary canal (A) and nervous system

(B) of an invertebrate. The upper brain mass (c) and the lower

brain mass (d) constrict the alimentary canal (after Wood Jones

and Porteus). Bottom: section across the brain of a scorpion-like

invertebrate. The upper and lower brain masses (c and d) constrict the

narrow alimentary tube (A) in the centre of the brain (after Gaskell).

scorpion and spider-like animals, whose brain-mass has grown round

and compressed the food-tube so that nothing but fluid pabulum can pass

through into the stomach; the whole group have become blood-suckers. These

kinds of animals -- the sea-scorpions -- were the dominant race when

the vertebrates first appeared. . . . Further upward evolution demanded

a larger and larger brain with the ensuing consequence of a greater and

greater difficulty of food supply.' [2] Another authority, Wood Jones,

comments:

To become a blood-sucker is to become a failure. Phylogenetic senility

comes with the specialisation of blood-sucking. Phylogenetic death

is sure to follow. Here, then, is an end to the progress in brain

building among the invertebrates. Faced with the awful problem of the

alternatives of intellectual advance accompanied by the certainty of

starvation, and intellectual stagnation accompanied by the inability

of enjoying a good square meal, they must perforce elect the latter

if they are to live. The invertebrates made a fatal mistake when

they started to build their brains around the oesophagus. Their

attempt to develop big brains was a failure. . . . Another start

must be made. [3]

invertebrates -- the social insects behaviour is almost entirely governed

by instinct; learning by experience plays a relatively small part. And

since all members of the beehive are descended from the same pair of

parents with no discernible varieties in heredity, they have little

individuality: insects are not persons. Admiration for the marvellous

organisation of the beehive should not blind us to this fact. In

vertebrates, on the other hand, as we ascend the evolutionary ladder,

individual learning plays an increasing role compared to instinct --

thanks to the increase in size and complexity of the brain, which was

free to grow without imposing on us a diet of porridge.

I have called them the poor cousins of us piacentals, because each species

of pouched animal, from mouse to wolf, is of an inferior 'make' compared

to its opposite number in the placental series. Wood Jones (himself an

Australian) comments regretfully: '. . . They are failures. Wherever

marsupial meets higher mammal, it is the marsupial that is circumvented

by superior cunning and forced to retreat or to succumb. The fox, the

cat, the dog, the rabbit, the rat and the mouse are all ousting their

parallels in the marsupial phylum.' [4]

but of a vastly inferior construction. The ring-tailed opossum and the

bush-baby lemur are both arboreal and nocturnal animals with certain

similarities in size, appearance and habits. But in the opossum, a

marsupial, about one-third of the cerebral hemispheres is given to the

sense of smell -- sight, hearing and all higher functions are crowded

together in the remaining two-thirds. The placental lemur, on the other

hand, has not only a larger brain, though its body is smaller than the

opossum's, but the area devoted to smell in the lemur's brain has shrunk

to relative insignificance, giving way, as it should, to areas serving

functions that are more vital to an arboreal creature.

Other books

Storm Singing and other Tangled Tasks by Lari Don

The Story of My Father by Sue Miller

Mad Powers (Tapped In) by Mark Wayne McGinnis

Blossom Street Brides by Debbie Macomber

Once a Warrior by Karyn Monk

12 Christmas Romances To Melt Your Heart by Anthology

In the Palace of Lazar by Alta Hensley

Homo Mysterious: Evolutionary Puzzles of Human Nature by David P. Barash

Disciplining the Maid by Zoe Blake

Stolen by Botefuhr, Bec