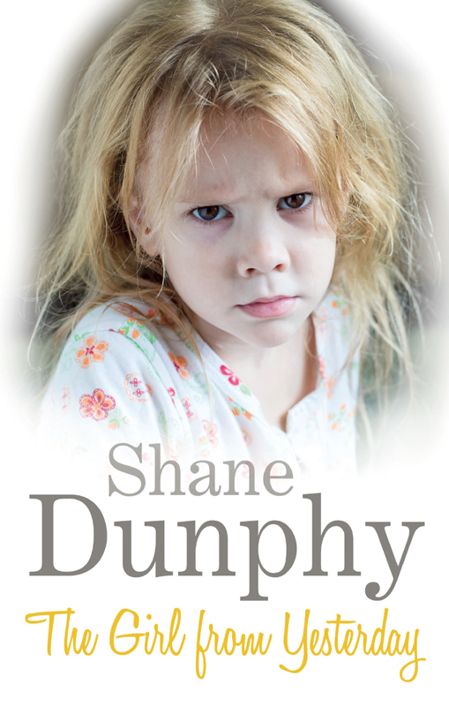

The Girl From Yesterday

Read The Girl From Yesterday Online

Authors: Shane Dunphy

Shane Dunphy

lives in Wexford, Ireland, and is a writer, musician, sociologist and lecturer. He is the author of several books about his experiences as a child protection worker. He is also a freelance journalist, writing mostly for the

Irish Independent

. Shane is a regular contributor to television and radio, and has produced several documentaries. He teaches Child Development and Social Studies at Waterford College of Further Education.

Yesterday

Shane Dunphy

Constable • London

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2014

Copyright © Shane Dunphy 2014

The right of Shane Dunphy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-47210-748-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-47211-124-1 (ebook)

Typeset by TW Typesetting, Plymouth, Devon

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Cover design by Shona

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more day by day

You tell me of our future that you plann’d;

Only remember me; you understand

It will be late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget me for a while

And afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and corruption leave

A vestige of the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should forget and smile

Than that you should remember and be sad.

Christina Rossetti

‘Why d’you come out here?’ the girl asked.

‘My boss asked me to come,’ I answered truthfully.

‘Why him want you t’ come?’

‘I suppose he wants me to get to know you.’

She thought about that one. She was very small for her age, looking more like a five- or six-year-old than her ten years. We sat in the unkempt grass of the field behind her family’s house. Her long hair was all curls and the same colour as corn.

‘Why he want that?’

‘I don’t know. Do you mind my hanging out with you and your brothers and sisters?’

She made an expansive shrug.

‘I don’ mind.’

I watched swifts chasing insects across the sky like fighter planes. We could hear the sea less than a hundred yards away.

‘I like bashin’,’ the girl said, as if this was a profound statement.

‘Bashing?’

‘Yeah. Want to help me bash?’

I couldn’t think of a reason not to.

‘Do you have a spare basher?’

She giggled, a delightful, musical sound.

‘I don’t gots no basher,’ she said. ‘I uses a stick. Le’s get you a stick. You’ll need a big one.’

She pushed herself up off the ground and skipped off.

We found a sturdy hazel rod in a clutch of trees that formed a border between two fields.

‘So . . . how do we bash?’ I asked.

‘I will show you,’ she said, and taking my hand led me to a small field, barely more than a copse, that had grass, cow parsley and ragwort that had grown taller than she was. ‘Now, we gots to bash a passageway through all these here weeds, and make a hideout in the middle.’

Bashing. Now I understood.

For a tiny thing, she had an impressive bashing arm. She used a thin ash branch, but she whipped it with such force she carved her way through the undergrowth at a tremendous pace. Every now and then she would pass a comment on my work or bark an instruction:

‘Tha’s some good bashin’ there, mister,’ or ‘Not too much on tha’ side – we wants the passage to be small, okay?’

In about forty-five minutes we had carved our way right into the centre of the field, and the girl, perhaps a little tired now, supervised my creating a circular space, like small room. She was remarkably thorough, even taking up the cut pieces of vegetation and throwing them away, so we were left with a patch of grass with a few stumps poking through, but mostly flat.

‘There you go,’ I said. ‘All done. So what are you going to do now? Plant some flowers here? Dig some holes?’

‘I’m gonna cover up the doorway,’ she said solemnly.

‘That door we made to get in? Out at the start of the field?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘ ’Cause this is a secret hiding place.’

I nodded conspiratorially.

‘For when you’re playing hide and seek?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘For when I need to hide.’

It did not rain on the day we buried Lonnie Whitmore – the sky stayed a dull metallic grey, but it did not open and soak the small congregation. A murder of crows perched atop a half-dead ash tree, just off the path that ran past the freshly excavated grave. I thought this fitting, but the black-feathered birds did not take to the sky in a flurry of ominous beating wings as the coffin was lowered.

The ceremony was . . . nice.

I stood apart from the group and wondered what I was going to do. The priest droned his way through a decade of the rosary. Three of the thirty or so people gathered responded in the appropriate places. The rest looked numb and ill at ease.

Lonnie had been my friend. Maybe even my best friend. He had died suddenly a week previously of a heart attack caused by a congenital problem associated with his particular form of dwarfism. Lonnie had spent most of his life locked away from prying eyes by a family who were ashamed of how he looked. When he finally came out of hiding he blossomed: I knew him as a proud, funny, irreverent man who apologized to nobody for his apparent strangeness. When he died he was manager of a crèche for children with special needs and in a relationship with Tush Cogley, a pretty colleague. He left the world a happy, fulfilled man.

I had not seen Lonnie at all the month before he died. We hadn’t fallen out nor were we estranged in any real sense: life just seemed to get in the way. I had taken on more responsibility in Drumlin Therapeutic Training Unit, a day care centre for adults with intellectual disabilities where I worked, and he had taken over the running of the crèche we had both wrestled from the brink of closure, bringing it to even greater levels of excellence.

I told myself that he had a girlfriend, his career was taking off and that he did not need me hanging around, getting in the way. But the truth was I had been remiss: a bad, neglectful friend. I realized too late that Lonnie’s first faltering steps as a manager would have been a time he really needed a listening ear; at the time I hadn’t wanted to know, burying myself in my own work. On the day I was told of Lonnie’s passing, I checked my phone and saw that I had three messages from him going back over a fortnight, all suggesting we get together and catch up. I had not responded to any of them.

I watched as my boss, Tristan Fowler, and some of my fellow workers from Drumlin huddled by a grove of ash, chatting quietly, solemnly.

‘I’ll see you around, Lonnie,’ I said under my breath, and as the world misted in tears I walked through the cracked and lopsided gravestones to the road.

Cowardice had become my modus operandi. I scrawled a letter of resignation sitting at the little kitchen table of my rented cottage. My plan was to drop it through Drumlin’s letterbox on my way out of town. I put a month’s rent in an envelope and added a note of apology to Barney, my aged but surprisingly sprightly landlord, informing him cryptically that my circumstances had changed, and thanking him for all his help and support during the three years of my tenancy. It took me all of an hour to pack up what I needed, and I boxed the rest and left what was still usable outside the local community centre, a stuttering message on the parish priest’s voicemail asking him to pass my garden tools and odds and ends on to someone who might need them – I had no room for such luxuries, and did not see myself having much call for them in the immediate future.

Tush answered the door to me on my third ring. She was in her late twenties, a good ten years younger than me, and her pretty face was stained red from crying, her blonde hair tousled and uncharacteristically awry. She said nothing but stepped aside to allow me into the little house on the mountainside she and Lonnie had shared.

‘D’you want tea?’ she asked. ‘I was just about to make something.’

‘No, thank you,’ I said. ‘I’m not staying long. I just . . . I just wanted to see how you are.’

‘I’m shit, thank you very much,’ she said, sitting on the couch and motioning at a chair opposite. I perched on it awkwardly. I shouldn’t have come. I could have made a clean getaway.

‘Yeah,’ I said, looking at my hands and then the floor. ‘I bet you are.’

‘I don’t know what to do with myself,’ she said. ‘I clean the place and wash clothes and pick flowers for the window, just like we used to do – I mean, you know the state he kept this place in before I moved here . . .’

I nodded and tried to smile. When Tristan and I first visited Lonnie, the house had sagged under the weight of neglect, every room a clutter of oddments, religious paraphernalia, old newspapers and dust. When Tush arrived she had immediately brought a woman’s touch without purging the place of Lonnie’s larger-than-life personality: if anything she had allowed his tastes to take shape in a more controlled, less frenetic way. A plastic figurine of Jesus stood on the mantelpiece beside an action figure of Darth Vader, the two leaning in to one another as if they were confiding secrets. On the wall above was a framed poster of Lonnie’s beloved Sex Pistols, John Lydon snarling at the camera as if he was offended by it.

‘This is your home, Tush,’ I said. ‘That hasn’t changed.’

‘I don’t know if I can continue living here without him.’

‘You can always sell the place,’ I said, ‘not that you’d get much for it right now.’

She said nothing to that, instead blowing her nose loudly into a tissue.

‘What do you want, Shane?’

‘To see that you were okay, and to say goodbye.’

She looked up sharply.

‘Where are you going?’

‘I don’t know. Away from here. Somewhere new.’

‘But your job. Your house. Millie . . .’

‘Millie is coming with me, of course,’ I said, referring to the greyhound Lonnie and I had more or less shared before we started to drift. ‘I’ve resigned from my job, and I’ve given back the keys to the cottage.’

‘Why?’

‘I came here three years ago to start a new life, a different life, and I ended up getting sucked right back into the same patterns of behaviour, a similar type of job; I might as well have stayed in the city. Lonnie dying has made me realize that I have nothing to tie me here.’

‘What about me?’ she said, hurt dripping from her voice. ‘What about all your friends and all the clients at Drumlin and . . . and the

life

you’ve built here? Have you given it any thought at all?’

‘I’ve been thinking about it a lot, Tush. For a long while, now. Since I left Lonnie to run Little Scamps, if I’m honest.’

She stood up and walked to the window.

‘Lonnie really looked up to you,’ she said. ‘You were some kind of hero to him: he really aspired to be like you.’

‘He never had any fucking sense,’ I said, fighting hard not to start bawling.

‘He thought you had it all sussed,’ Tush continued as if I hadn’t spoken. ‘Oh, he’d make jokes about you, call you a bleeding-heart hippy and so on, but it was all to hide his complete idolatry of you. You saved him, you see. And despite everything, you always treated him like a person, not a walking condition.’

‘Not always,’ I said quietly.

‘He was planning to go back to college and get his degree,’ Tush said. “I’ll have letters after my name like the beardy fella”, he’d say. He was going to go at night. He laughed that you might even end up teaching him – you still do some part-time teaching, don’t you? He would have liked that, I think. He’d have been so proud.’

‘That would have been nice. A bit odd, but nice.’

‘He thought you had all the answers. But you don’t at all, do you?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘You’re just as messed up and scared as any of the rest of us.’

There didn’t seem to be anything to say to that. I sat and looked at her as she gazed at some spot on the horizon.

‘Go on,’ she said after a time, ‘run away. You won’t find peace or whatever it is you’re looking for anywhere else, you know. Guess what? You’ll bring whatever crap you’ve got floating in that black cloud you carry around over your head with you to whereever you’re going.’