The Girl in the Road (32 page)

Read The Girl in the Road Online

Authors: Monica Byrne

When I got to Autobus Terra, I began to truly fall back into my body. I could hear again, and everything was loud. My belly burned like it was on fire. I limped out of the car and ignored the stares and bought a ticket for Assaita and went into a stall in the women's bathroom, struggling to remain upright. I peeled up my T-shirt and untied the dressing gown I'd used to bind the wound. The pain was so great I thought I would faint.

I made myself take deep breaths. I knew you wouldn't abandon me now, having brought me so far. I had to have faith.

I leaned back against the wall to make my torso as flat as possible, then used my hand to move the two walls of the incision together. With my other hand, I peeled a stem-cell strip out of its wrapper and laid it across the wound. I added one more on top of that, and then three more perpendicularly just to make sure. The wrapper instructed me to bind it over with gauze, but I had none, so I picked the bloody dressing gown back up off the bathroom floor and re-bound it around my hips. Infection. I had to watch for infection. I swallowed four broad-spectrum nanobiotics, dry, for the time being. But I would need real medical attention soon.

The border with Djibouti was only 250 kilometers away. A matter of hours on smooth, paved roads. Surely I could hold out that long. I boarded the bus and collapsed in a back seat and watched the screen mounted in the ceiling. The PEP's victory was clear. I looked out the window and saw young women and men tearing down the street and shouting, rocks in hand, probably on their way to Meskel Square or the Presidential Palace. Oh, Yemaya, I could see the following scenes play out like a movie. All our noble student efforts had amounted to nothing.

So it goes, I said to myself.

The pain was swelling now, transforming me into a radiant being. But I knew you were with me in this final trial. I would wait and watch for the signs.

Meena

A False Ocean

HASSANIYYA

:

Yemaya, can it truly be you?

I remember what the sailors called me. So I say, “Yes.”

The little woman reaches for me, then snatches her hand back again and cradles it to her chest.

“It's you,” she says. “Forgive me. I forgot how many languages you speak. I feel like a little girl again. You always called me âlittle girl.' There's so much I want to tell you. I've already been telling you, for years, going to the place inside myself that is you, where the kreen used to be. But skin is skin. There's no substitute for skin. You're here the flesh. You're so beautiful, naked, as I remember, in the hotel room. Where have you been? What have you been doing?”

The sun is setting directly behind her and Venus is rising above it. I stare at it. I'm still in the same universe. I don't know who she thinks I am, but I give the only answer I have.

“I hurt someone,” I say.

“Hurt someone?” she says. “Who?”

“Someone I loved.”

“They must have hurt you first.”

I shift my eyes to her.

“Oh, Yemaya, I know how that feels,” she says. “Stay with me. I'll tell you everything.”

So I wait for her to continue.

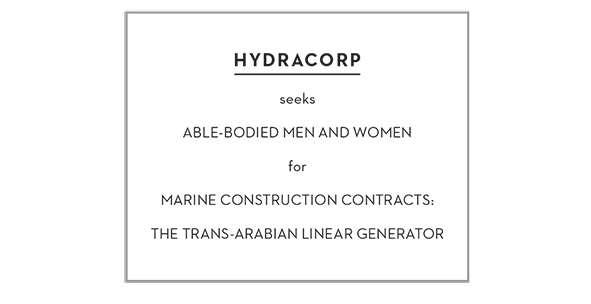

Months later, I was in Djibouti City, washing the floors of a convent and still watching for signs, when a nun handed me an old-fashioned flyer.

And I remembered the wave array from my student protest days.

I went to the recruitment session at Port of Djibouti, where a large crowd had gathered, and a beautiful woman in a fine silver suit spread her hands wide, between which appeared a holo of a sea snake that spanned the entire Arabian Sea. Of course it wasn't a sea snake, Yemaya. It was the Trail. But as soon as I saw it I remembered your story from the clinic all those years ago, and I knew it was the final sign. The Trail was where you would reveal yourself to me.

Can I go? I asked.

Of course, you said. I'll meet you there.

Ten years later, I was assigned to the ship carrying the last scales to their destination. In the middle of the night, when all the crew slept, I slipped out of a hatch by moonlight. I swam to the Trail just a kilometer away from where our ship had dropped anchor. I pulled myself up. At first I crawled, and then I walked, and by morning I was far, far away.

Night has passed and the stars have cartwheeled overhead. Now by the light of the eastern horizon I see the little woman's cowrie-shell mouth is shaped like mine.

So this is my mother.

I'm so tired. After everything, this is all the final chamber is, was, and ever will be, the concrete shack where her own mother is upside down, mid-rape, saying she'd be all right, on repeat, forever. That was the end of her life. There's nothing anyone else can say to her. I don't have the energy to try, even if it set the course of my life as a bloody baby trying to enter people who are not my mother.

There's nothing anyone can say to me, either.

So I just say, “Thank you for the story, little girl.”

Then she asks if she can touch my face.

I say yes.

She crawls forward and reaches for me, and her skin is like leather, and she stinks of sweat and sour brine, and she wraps her arms around my head, like she's forgotten how to hug. I tell myself: My mother is hugging me. This should feel good. But it doesn't. She's hugging my head to her chest more tightly and my arms are limp at my sides. I open my eyes and see blackness. She squeezes harder and harder. I start seeing sparkles. She wants to consume me.

I push her away.

She looks terrified. She curls into a ball and rocks. “Have I angered you, Yemaya?”

“No,” I say. “I just couldn't breathe.”

“Forgive me,” she says, uncurling and reaching for me again. “I just wanted us to be together again, one and whole, as before.” Then with a shy look dawning in her eyes, she lies back and parts her legs before me. Her yoni is soft and hairless from age.

I look away. I focus on the sea. I try to imagine what the goddess would do. I try to imagine what would make us whole.

I crawl forward and lie down next to her and turn her over and hug her to me like she says Yemaya used to hold her. She's fragile. Her body expands and collapses. I breathe her in and now under the brine I smell a faint violet smell from a recurring dream I've had all my life but couldn't remember till now.

For a time, we sleep, and share that very dream.

We wake near dawn, when the clouds are sage and gold.

She turns over and holds my face in her hands and says, “I am yours, Yemaya, as I always was. Take me.”

It begins to rain.

So this is how the Trail will end for me. A Trail-ending rain, a world-ending rain. I think again of holding the knife, the blade with the infinitesimal edge, that could cut everything, palms, saris, salwar kameez, fruit, the metal of trains, and people. Here the world is already split in two for me: sky, sea. But now in the rain they blur into one continuum. So does the Trail. I wonder where the real Yemaya is now. I wonder what her real name was. Maybe she did go to Addis, for a few months, feckless, to go slumming and do the artist thing, only to realize that she had no skills and no job prospects, only to move on to another imagined paradise, and then another and another, because she could never go back home. I begin to see visions of Africa, coming from the west. The fantasy of flotillas was naïve but surely I'll be welcomed, somehow. Who else has walked this far. Who else has stepped off the edge into the arms of the continental shelf. I want to be a hero for practical reasons: I'll be taken care of: I'll be given a bed and warm food. I remember pictures of Djibouti. The sovereign nation of Djibouti. The colonial architecture. Cafés and sea spray. The musical legacy of which I know nothing but have no doubt exists. A little crossroads of the world. A tongue of land. A continuation of the planet on which women and men, clean and healthy, go about their business on solid ground, in suits, with jobs, picking up pastries from kiosks on the way to work. Like waking from a dream I begin to remember what real food is like. Hot food with different kinds of things in it. Hot food over rice. Pappadams that crackle. Spices. Cold icy drinks and hot steaming drinks. Sugar. Pickles. I have to spend the next few hours wisely. I have to conserve energy. Even though I've lost the strength to walk I still crawl, down the midline, not permitting myself to think except about food. I have to make it to land. I have to see whether life continues, after I laid my mother on top of the waves and let her sink, and watched her head bend back, and her little body turn in the current until I couldn't see it anymore, and then I closed my eyes and watched her from the inside, and saw her pass through the warm upper reach, then cross the boundary into the freezing dark, descending down the gradient, down into darkness, then carried on currents to the deepest parts of the world, until her body came to settle in a place where the sky was always black and the moon was always new.

I have only two kilometers' notice that I've reached the end of the world, and I don't see land but I keep crawling because this is definitely the last and most cruel hallucination, made worse by the rain that confuses sea and air, and I'll pass through this veil like all the others, even though my mother is already found and lost again, life will be nothing but more veils to pass and pass through again. I know this now. There are yet more chambers. I crawl to the end.

The scales end in the middle of the sea.

There's no land in sight. I think that there must have been a catastrophic break where the Trail drowned and didn't re-surface and I get frantic and plunge my hands down into the water, but feel the two mooring cables that I remember running into below the surface, at the very beginning, in Back Bay. This is definitely the end of the Trail.

I dig out my pozit. I'm only a kilometer offshore. I should be able to see land. But then I see a flock of hovercraft glinting in the distance, turning this way and that, swimming through the air like a school of fish, low over the water, and now I understand that the sovereign nation of Djibouti is nowhere in sight because the sovereign nation of Djibouti is gone.