The Glass Room (49 page)

Authors: Simon Mawer

Tags: #World War; 1939-1945 - Social aspects - Czechoslovakia, #Czechoslovakia - History - 1938-1945, #World War; 1939-1945, #Czechoslovakia, #Family Life, #Architects, #General, #Dwellings - Czechoslovakia, #Architecture; Modern, #Historical, #War & Military, #Architects - Czechoslovakia, #Fiction, #Domestic fiction, #Dwellings

When she comes Hana looks anxious and slightly confused, like someone who has just woken from a deep sleep and is not quite certain of where she is. They greet each other cautiously, neither of them alluding to what has gone before. Zdenka goes into the kitchen to make coffee, the

turecká

, Turkish coffee, that Hana likes. ‘How are you?’ she asks as she brings the coffee out. There is something about the enquiry that makes it sound like what you might say to someone who has recently been bereaved.

Hana is standing at the window looking at the view. It is always the view that draws the eye. ‘I’m fine.’ Then she adds, ‘Look, there’s something I wanted to tell you. I think I should have said this the last time. So that you know everything about me.’

Zdenka is about to speak, but Hana holds up her hand. She attempts a smile. ‘Please. I want you to know everything before you say anything.’

Zdenka places the glasses of coffee on the table. The coffee grains are settling in the bottom of the thick dark liquid. ‘All right, tell me.’

Hana lifts the glass to her lips and blows softly across the surface of the coffee. She sips, cautiously in case the liquid is too hot. Then she puts the glass down with exaggerated care. ‘You see, I’ve never told anyone. Never.’

Is the Glass Room a place for secrets? Surely it is a place of openness and transparency, a place where no one can tell lies.

‘I had a baby. In the camp, I mean. In Ravensbrück.’

Zdenka gasps. She has been expecting other things, the careful broaching of the subject of their last conversation, the question of Hana’s love, with all the incongruities and difficulties that it implies; and instead there is this: I had a baby in the camp.

‘A

baby

?’

‘I’ve never told anyone before.’

‘You gave

birth

in the concentration camp?’

‘That’s what I said.’ Her features have that rigidity, the expression of a mourner at a graveside. She looks away through the window at the view. There is silence. Zdenka cannot, dare not ask anything more. Hana’s presence, her very existence, seems to hang on a thread. ‘I wanted you to know, that’s all,’ she says, as though somehow the knowledge is a gift, a small, very fragile but very precious gift.

‘Who was the baby’s father?’

‘It was the German I told you about. The German scientist.’ She looks at Zdenka and smiles. It is a curious smile, without humour, infested with sorrow. ‘I always thought I was barren. I would have loved a child, but it never happened with my husband, nor with any others that I went with. I suppose that’s shocking enough, isn’t it? That I tried with other men. And then this German … He didn’t want to have anything to do with it, of course he didn’t. But I wanted the baby.’

This confession hits Zdenka with an almost physical force, like a blow across the face. She feels the sting of tears. ‘Haničko,’ she says. Just that, the diminutive of Hana’s name. Nothing more because she can think of nothing more. There are no words of comfort.

‘And then they arrested me and took me off to hell and I wanted the baby even more. Can you believe that? I went to somewhere in Austria first, somewhere near Linz, and then they put a whole lot of us on a train — cattle trucks, just thrown in like animals — and we went right across Germany and ended up somewhere to the north of Berlin. Of course we didn’t know that then. It was just a wilderness. Barbed wire and rows of huts. The women in my hut looked after me. The place was chaos and things like that happened, women looking after you, women giving birth. All sorts of things happened.’

Zdenka is silent, almost without breath. Breathing seems difficult, as though something is constricting her throat. Eventually she dares to speak. ‘Was it a girl or a boy?’

‘A little girl. Just a little girl. She had dark hair, I remember. And a wrinkled face like an old woman’s. And she cried, a short, sharp cry as though she was gasping for air. Perhaps she was, I don’t know. I even gave her a name. I called her Svĕtla. Light in the darkness. I loved her. There I was in the middle of hell and I had found love.’

‘And what happened to her?’

‘They put her to my breast for a while. She tried to feed, but of course I didn’t have milk. Nothing. And then they took her away.’ She looks at Zdenka and shrugs. ‘I never saw her again. That’s what they did then. Later on they had a maternity hut and women were allowed to keep their babies for as long as they could. As long as they lasted. But when I had Svĕtla that is what they did. They just took the babies away.’ Hana seems to gasp for air. It is as though the Glass Room has suddenly become airless. ‘I used to imagine that somehow she would survive and we would be reunited when it was all over. If I had died, then my side of that fantasy would not have been fulfilled, so that became a reason to survive. I suppose you could say that Svĕtla saved my life.’ She begins to weep. There is no drama, no convulsion, just the slow seepage of tears. ‘I’m sorry,’ she says. ‘I have never told anybody any of this, do you realise that? Never. By knowing this you know all about me. There’s nothing else.’

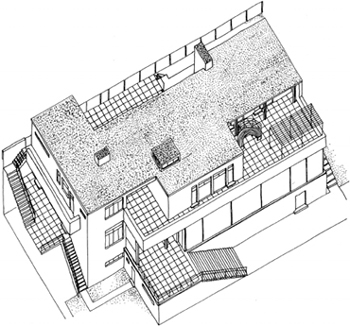

Against this story the myth of Ondine is nothing. Against this, Tomáš’s denial of history is a mere fancy. History is here and now, in the beautiful and austere face of Hana Hanáková. There in the Glass Room of the Landauer House, feeling as helpless as a person at the scene of an accident who doesn’t know how to staunch the bleeding, Zdenka goes round the table and puts her arms around the older woman and tries to comfort her. And all around them is the past, frozen into a construct of glass and concrete and chrome, the Glass Room with its onyx wall and its partitions of tropical hardwood and the milky petals of its ceiling lights, a space, a

Raum

so modern when Rainer von Abt designed it, yet now, as Hana Hanáková sits and weeps, so imbued with the past.

Veselý had driven from the city that morning and had lunch at a diner in Falmouth. They’d followed him of course. They were driving a two-tone Oldsmobile and he kept them in his rear-view mirror easily enough all the way through New Haven and Providence and across the bridge at Bourne. When he went into the diner they even followed him in and sat down just three tables away, two fresh-faced, crew-cut exemplars of the American way of life, the kind that would have been in the army if they hadn’t been in this line of work.

He had been warned clearly enough. ‘Make it easy for them,’ the security officer had said. ‘Drive slowly and steadily and don’t make any hasty turns. You make it difficult for them and they’ll make it difficult for you.’

When the menu came he ordered baked scrod, and then went to phone the embassy. He was under instructions to report in at regular intervals. They wanted to know that everything was all right, that no political incident had occurred, no one had kidnapped him and that he had not decided to defect. That was the irony of the matter: they were as much checking on your own loyalty as your safety.

As he got up from the table one of the men followed him. Perhaps they thought he was going to leave by the back door. Should he should acknowledge the man’s presence? Should he say hi and wish him good day or something? But in the event he just dialled the number and stood there holding the receiver to his ear as the man went past to the men’s room.

‘Falmouth,’ he said when the duty clerk answered. ‘At a diner … No, I don’t know the address. Does it matter? Betty’s, that’s what it’s called. Yes, Betty’s.’

Then he cut the connection and dialled the place he was going, the woman he had already spoken to, just to confirm his appointment for the afternoon. She hadn’t forgotten. No, of course it was all right. She would be waiting for him. She sounded wary on the phone, suspicious of this man from the Embassy. But then, who wouldn’t be?

The man came out of the men’s room and went back to his table just as Veselý hung up the receiver so by the time he got back to his own place both of his followers had resumed their meal and their subdued conversation and their undisguised examination of the prettier of the two waitresses. They didn’t look at him and didn’t even bother to move when he paid the check and got up to go; yet the Oldsmobile was behind him again when he drew out of the parking lot.

From Falmouth he followed the coast road. It was a fine, sunny day and the sea glittered, creaming along the beach to the left. He was in good time, so where the road ran along a spit of land between the ocean and a brackish inland lagoon he pulled the car over to have a look. There were beach houses among the dunes. Gulls screamed overhead. Sailboats tacked back and forth between the shore and the island that lay offshore. The Oldsmobile waited in the background while he stood there savouring the breeze and the taste of salt on his lips. They were probably wondering what the hell he was up to. Searching for submarines, maybe. But all he was doing was looking at the ocean, because he had never seen it before.

At Wood’s Hole he stopped at a gas station to ask for directions. The pump attendant scratched his head. ‘The Landor place, you say? That’ll be Gardiner Road, I guess.’ The Beatles blared from a transistor radio in the shack at the back of the forecourt. ‘Lady Madonna’. They had been playing it in Prague when Veselý had left only two weeks ago. The pump attendant gave directions and then looked at Veselý sideways. ‘Where you from, then?’

‘Czechoslovakia.’

The man nodded. ‘That’ll be communist,’ he said, as though sharing a piece of exclusive information.

‘More or less.’

‘Can’t say I approve of them Commies. But now they say things are different, at least in your neck of the woods.’

‘For the moment,’ Veselý said. ‘We’re keeping our fingers crossed.’

‘Them Russians. That’s what you want to watch.’

Wanna watch

. Veselý agreed. We wanna watch them Russians.

It wasn’t difficult to find the house. It was numbered plainly enough and there was even the name on a board by the mailbox: Mahren House. They’d left the umlaut off which was typical enough of the whole country really — anything to make things easy. He turned in to the driveway and pulled up in front of the door. The house was one of those clapboard buildings that abound in that part of the world, an expensive place with gardens all round it and two cars in the carport and boat on a trailer parked alongside. He noticed a man standing at a downstairs window watching as he climbed out of the car, but when he rang the bell the door was opened by a woman. She was far too young to be the one he was going to visit. She was blonde, and dressed younger than she looked: jeans and a kind of kaftan top, with her feet in sandals. You could imagine her listening to Dylan and The Byrds and arguing about Vietnam. Or strumming a guitar and playing ‘We Shall Overcome’. Or sailing. You could imagine her out to sea with the salt wind in her hair. A little boy, equally blond, stood watching from the back of the hall. ‘Yes?’ the woman asked.

‘I’ve come from the Embassy. I rang earlier to confirm. To see Mrs Landor.’

She flashed a nervous smile, just a flicker of welcome. ‘I’m her daughter. You’d best come through.’

The house was all wood inside, wooden floor, wooden walls, wooden ceiling. Like a glorified

chata

, he thought. ‘Maminko,’ the woman called as she showed him into the living room, ‘it’s the man from the Embassy.’

The living room spanned the whole depth of the house. It was a cool, expansive place with modern furniture. The paintings on the walls were abstracts with a vaguely nautical feel to them, as though the strokes of paint were sails and hulls, the blocks of blue and white were sky and clouds. A picture window showed the lawn at the back and, beyond some bushes, an azure smear of sea. The breath of air conditioning was like a sea breeze.

There were two other people in the room, a woman sitting in an armchair beside the unlit fire and a young man standing by the window that overlooked the front drive. The woman was in her sixties, Veselý guessed. Her hair was pulled back to show fine, strong features. There was the shadow of her daughter there in the shape of her face. Her grip was firm as they shook hands but her look was wayward and uncertain, as though Veselý was not the only person she was expecting and she was trying to see if there was anyone else coming through the door behind him.

‘Please sit down, Mr Veselý,’ she said. She spoke in Czech but with a heavy German intonation, an amalgam of sound that came out of the past, from a time before the revolution and the war. ‘It’s most unusual to have a visit from the Embassy.’

The young man — no older than Veselý himself — turned from the window. ‘There’s an automobile out there with two men in it.’ He spoke in English. ‘They’re watching the house from across the road. Is that anything to do with you?’

‘They follow us wherever we go.’

‘Who do?’

‘The FBI. Domestic Security Division.’

‘You mean those guys are on

our

side?’

Veselý shrugged. The man seemed angry about something, but what was there to be angry about? The meeting had been arranged in advance and Mrs Landor had seemed happy to go through with it. It was hardly Veselý’s fault that the American authorities tailed him. ‘I don’t see it as being a matter of sides.’