The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (105 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

had a hundred loyalists with them. Greene, however, believed the exaggerated reports and, with a vision of the Carolinas returning to the British fold dancing in his head, felt compelled to do something to dampen enthusiasm for the king. He therefore sent his army back across the Dan, first Otho Williams with the light corps, and on February 23 the main army augmented by 600 fresh Virginia militia.

37

Cornwallis responded four days later by moving to the southern side of Alamance Creek, to a junction of roads linking Hillsboro to the east and Guilford and Salisbury to the west. Over the next two weeks each side maneuvered carefully, staying near the Alamance and tributaries of the Haw River. They fought several skirmishes but no heavy actions though Cornwallis desperately yearned for a major battle. While the American army moved, it grew as Steuben and Virginia sent 400 Continentals and 1693 militia, who were pledged to serve for only six weeks. North Carolina sent two brigades of militia, 1060 men in all. His army significantly larger than the British, Greene now felt strong enough for a battle, and on March 14, he marched to Guilford Court House. He would fight on ground of his own choosing.

38

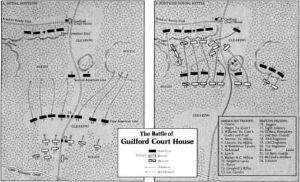

Guilford Court House sat on the edge of a small village clustered on a hill. Below the court house looking to the southwest a valley unfolded cut by the Great Road, a rough track from Salisbury. Although the high ground around the court house was cleared, most of the valley was wooded. The enemy coming along the road would have to enter through a defile formed by two low hills. There, at the opening of the valley, the ground on either side of the road had been cleared for the cultivation of corn. On the east side there were two fields, one abutting the road, separated from one another by woods 200 yards wide. The valley sank gradually from the defile to Little Horsepen Creek for a distance of one-fourth mile and then rose again for another fourth to the edge of a wood.

39

The ground was Greene's; the tactics were Daniel Morgan's. Greene like Morgan at Cowpens resolved to use a defense that had depth, a defense of three lines. The first that Cornwallis's troops would hit was stretched out along the edge of the woods north of the open fields.

____________________

37 | Rogers, ed., "Letters of O'Hara", |

38 | Ward, II, 782-83. Chapters 71 and 72 in Ward provide a superb account of the chase by Cornwallis of Greene. |

39 | Wickwires, |

To reach it the British would have to go down into the valley and then climb up slopes exposed to American fire. To give that fire Greene deployed the North Carolina militia, 1000 in number, on both sides of the road. He anchored their right flank with 200 Virginia riflemen and 110 Delaware Continentals; Colonel William Washington's cavalry, probably about eighty horse, backed them. On the far left he placed about 200 Virginia riflemen and 150 of Henry Lee's Legion, about half of whom were cavalry, the others infantry. All Greene asked of this line was that it deliver two volleys before retiring. At its center on the road he set up two six-pounders, guns with a range of 600 to 800 yards.

40

Three hundred yards behind, he set up a second line, two brigades, 600 men each of Virginia militia under Brig. Generals Edward Stevens and Robert Lawson. Historians of the battle do not agree on the relative alignments of these two, but Stevens's men seem to have been on the right (or west) side of the road. The entire line was in the woods.

The third and main line occupied the high open ground just below the court house. It was entirely to the right of the road which swung slightly northeastward as it came up the hill. Because of the configuration of the ground this line was at a slight angle to the second and between 500 and 600 yards behind it. General Huger commanded the right side composed of almost 8 Virginia Continentals, and Otho Williams, the left, of a little more than 600 Maryland Continentals.

The British began the twelve-mile march to Guilford in the darkness of early morning. They had not eaten, having run out of flour the day before. Cornwallis posted Tarleton several miles ahead, and about 10:00 A.M. Tarleton's horsemen collided with Lee's, who had been sent out to give Greene warning of the enemy's approach. Several riders were wounded on each side in this short encounter, and Tarleton took a prisoner or two. The captives were unable to tell Cornwallis anything about American dispositions, however, and when he entered the valley leading to Guilford he was ignorant of what was ahead. He had been over the ground before, of course, but seems not to have remembered much about it.

41

The six-pounders with the first line opened up on his troops as they passed into the valley. The British artillery soon came forward to answer, and Cornwallis formed his line.

On his right, under Leslie, he placed

____________________

40 | Ward, II, 786-87. |

41 | Cornwallis to Germain |

the regiment of Bose, the 71st, and the First Battalion of Guards in support; on the left of the road, under Webster, he assigned the 23rd and 33rd Regiments supported by grenadiers and the Second Battalion of Guards under O'Hara in support. The jaegers and the light infantry of the guards remained as a reserve in the woods to the left, and Tarleton also in reserve took the road. Altogether the army numbered about 1900 men.

42

The North Carolinians standing behind a rail fence at the skirt of the woods watched the regularis march forward to pounding drums and squealing fifes. The British right started first, following Leslie's commands. After looking the valley over, Cornwallis had decided to begin action on the right because the trees and brush were not as dense there as on the left. The North Carolinian commander facing the British right waited while the enemy marched down the slope, crossed the creek, and moved up the hill. At 150 yards he ordered his men to fire. The Carolinians' rifles killed at that range, and the British line immediately showed great holes. An observer commented that the row of redcoats "looked like the scattering stalks in a wheat field, when the harvest man has passed over it with his cradle." A captain in the 71st gave a flat description of the sight which is even more telling of the loss of life -- "one-half of the Highlanders dropped on that spot." Only superbly disciplined and proud troops would have come on without wavering. Leslie ordered the pace to be picked up, and when the line got within what he considered effective range he stopped it and gave the command to present and fire. The Highlanders, again on order, then shouted and ran toward the Carolinians with muskets, bayonets attached, thrust forward. The Carolinians seem to have panicked at the sight. Henry Lee who was on the American left with his legion later wrote that in their eagerness to escape, they dropped their rifles, threw off knapsacks, and even discarded their canteens. Lee tried to hold them in place, even threatened to shoot them if they did not remain, but the Carolinians heard only Highlander yells. They would take their chances with Lee rather than their grim enemy.

43

The Carolinians to the right of the road may have held their places a few moments longer. Lt. Colonel Webster, the British commander opposite them, sent his troops forward after Leslie got under way. The Carolinians on the right, like those on the left, waited patiently but

____________________

42 | Ward, II, 787; Wickwires, |

43 | Quotations are from Wickwires, |

seem to have fired simultaneously with the Americans on their left. Webster responded immediately by commanding his men to charge, hoping to reach the line before the Americans could reload. Sergeant Roger Lamb of the Royal Welch Fusiliers said that the movement was made "in excellent order, in a smart run, with arms charged." When the British got to within forty yards of the Carolinians, they discovered that they faced men resting their rifles on the rail fence "taking aim with the nicest precision." There was a pause while each side looked the other over until Webster rode in front of the 23rd shouting, "Come on my brave Fuzileers." The line moved again, both sides fired, and finally the American "gave way." Lamb reported no panic among them.

44

Up to this point the action can be reconstructed fairly easily. There was disagreement in the days that followed -- and since -- about the steadiness of the first line. In his memoirs written years later, Henry Lee blamed the Carolinians for the loss of the battle, surely an unfair charge whatever the truth about their exit from the field. Greene, who was near the court house, too far away to see the first line, also dealt them a heavy load of blame.

45

Sergeant Lamb wrote that after the British swept over the first line and into the woods, the action took on a ragged, even unconnected, quality. Visibility in the woods was frequently obscured by the heavy undergrowth which also broke up the evenness of the line. The British complained after the battle that they had found using the bayonet almost impossible, meaning that the heavy concentration of a bayonet charge could not be maintained by men entangled in brush and deflected by trees. The Virginians on the second line understandably regarded the trees and brush differently -- as cover from which to avoid the bayonet and to shoot down their attackers. In the woods the attack broke into a series of smaller assaults and charges; no unit on either side had a clear notion of what was happening on its flanks.

46

On the extreme edges of the battlefield two separate and savage engagements were fought. Lee's and Campbell's riflemen on the American left had not joined the Carolinians in flight. Rather they had fired down the British line as it came abreast of them. So galling was this enfilade fire, that Leslie committed his support, the 1st Battalion of Guards, to clean the Americans out.

The guards fought tenaciously but only suc-

____________________

44 | Roger Lamb, |

45 | Lee, |

46 | Lamb, |