The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (80 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

____________________

44 | Ibid., |

45 | GW Writings |

by local partisans and raiders from the west bank of the Delaware. Rall did not even bother to throw up fortifications around Trenton; the enemy surrounded him -- he explained -- and he could not begin to cover himself adequately.

44

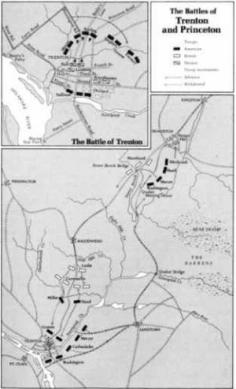

Neither Rall nor his chief expected Washington to attack Christmas night. The weather was bad, with rain and snow; the Delaware, though not covered with ice, carried large pieces of it downstream. Washington planned carefully, though he had not expected the weather to conceal his movements. His attack was to have three parts: James Ewing with 700 troops would cross at Trenton Ferry and seize the bridge over the Assunpink Creek just to the south of the town. Lt. Colonel John Cadwalader farther to the south would strike over the river at Bristol and hit Donop's force at Mt. Holly, a diversion to keep the Hessians so occupied there as to prevent reinforcement of Trenton. And Trenton itself was the main objective and would be attacked by Washington, who, if all went well, planned to push to Princeton and perhaps as far as the main magazine at New Brunswick.

45

After dark on Christmas night, the main force, some 2400 soldiers, assembled behind the low hills overlooking McKonkey's Ferry. Washington wanted to cross them all by midnight and march them south the nine miles to Trenton by five in the morning, well before daylight. The storm, the rough water, and ice prevented him from holding to this schedule. The artillery under Knox, eighteen fieldpieces in all, proved difficult to handle in the snow and sleet and was not ashore until three in the morning. Washington, who had crossed with the advance party in Durham boats, stood on the bank and watched -- he knew that his presence would not go unnoticed even in the dark. By four o'clock everyone was assembled for the march into Trenton.

Two columns were formed, one on the upper or Pennington Road, the other on the lower or River Road. Washington, with Nathanael Greene, commanded the force on the Pennington, and Sullivan led on the River Road. By skill or by good luck, both groups reached Trenton within a few minutes of eight o'clock. The River Road curved into the southern end of town; the Pennington Road carried the troops to King and Queen streets, running north and south, the main thoroughfares of the town. Washington's van drove in a company on outpost duty on the north edge and within a few minutes had set up their artillery on King and Queen streets.

Two young captains commanded these

____________________

44 | Ibid., |

45 | GW Writings |

to recover the initiative, and Cornwallis pushed down from Princeton with 5500 regulars and twenty-eight fieldpieces. Washington did not ease his way south. The Princeton Road was churned into mud, and small parties of Pennsylvania and Virginia Continentals harassed the British as they marched. Late in the afternoon of January 2 Cornwallis arrived at Trenton to find Washington drawn up along the ridge of Assunpink Creek. Several unsuccessful attempts to ford the creek by advance units left Cornwallis convinced that he should delay a major assault until the morrow. A subordinate or two protested, saying that Washington would not be there in the morning. The answer to that was a question: Where would he go? He had no boats; he was trapped.

47

That night Washington provided a different answer by slipping away on a recently constructed road southeast of the worn highway to Princeton. The British did not discover his departure until dawn, for the Americans had left behind several hundred men who kept their campfires ablaze and who spent much of their time digging into the ground, making noise which reassured their enemies across the creek. By early morning Washington's van reached the outskirts of Princeton, where they ran into Lt. Colonel Charles Mawhood, who had been left there with two regiments. There was a desperate fight for a time with Mawhood's command roughing up troops under Hugh Mercer and John Cadwalader. Just as the American units threatened to lose their integrity as fighting organizations, Washington arrived on the scene. It was hard to resist Washington on horseback, and the Continentals pulled themselves together; the British began to fall apart. Mawhood eventually broke through to Trenton, but under severe pursuit his command virtually disintegrated.

48

The British regiment Mawhood had left in Princeton sat there inertly and then attempted to retreat to New Brunswick. Not all made it, as a New Jersey regiment captured almost two hundred. Washington soon saw that his troops were spent and gave up his design on New Brunswick. Four days later he entered winter quarters in Morristown. Cornwallis, fearing the worst from his slippery enemy, marched his command from Trenton to New Brunswick. He was taking no chances on losing his supply depot. Hackensack and Elizabeth Town fell to American forces on January 6, 1777, the day Washington's army entered Morristown. Howe, who had dominated New Jersey two weeks before, now saw his forces confined to Amboy and New Brunswick.

____________________

47 | Wickwires, |

48 | Freeman, |

The War of Maneuver

The two armies now settled in, apparently for the winter. A casual observer might have thought that it was Europe, the convention of going into winter quarters was so taken for granted. The soldiers on both sides turned to the business of making themselves comfortable or trying to find comfort in situations inherently uncomfortable. For Washington's men attaining some ease seemed almost impossible in the mean little huts they constructed for themselves. Keeping warm proved a challenge -- central heating awaited the genius of a later century -- but collecting firewood at least forced the men to stay active. Their opposite numbers in New York City did not swelter, but they made themselves snug in taverns, public buildings, and private homes.

Some of Washington's men at Morristown followed the ways of many who had served before them -- that is, they did what was becoming the American practice, ending their military service without authorization; in other words, they deserted. Howe too lost troops to desertion, but not as many. Where, after all, could redcoats go except to the enemy?

The citizens of New York City soon came to envy the deserters. Life in the city deteriorated as winter set in, and the occupying army did nothing to improve it -- for civilians at any rate. Food was scarce, as irregulars on Long Island and across the Hudson struck at foraging parties. This little war was barbarous and dirty and conducted according to none of the familiar rules. Inside the city, citizens were safe from raiding parties, but there the regulars either ignored them or pushed them around whenever they bothered to notice. Eighteenth-century garrisons and the civilians they "protected" never appreciated one another, and what the New Yorkers endured in the winter of 1776-77 had taken place many times before, most recently in Boston. The regulars in both places aimed to destroy the enemy and ended by adding to the enemy's numbers.

At the same time, Washington's troops soon lost some of their admirers in Morristown -- not because they misbehaved, but because they brought smallpox with them, and because their commander insisted upon spreading out the sick among the townspeople for care and in order to "isolate" the sick. Congress had dismissed the director-general of hospitals, Dr. John Morgan, three days after Washington's forces arrived at Morristown, and hospitals which had never been adequate soon fell into deeper disrepair. Washington had no recourse other than his regimental hospitals and the town itself -- thus his attempt at isolating smallpox patients and a try at inoculation, a technique which called for deliberately infecting those who had not yet contracted the disease in the hope that they would survive the less virulent form that usually resulted. Understandably, the farmers of Morristown looked with dismay at the changes in their lives that the army brought, and the cost of their principles was borne in upon them.

1

The village itself was small -- no more than fifty houses, a church, and the inevitable tavern -- and by all standards a well-chosen site for winter quarters, difficult of access from the east through hills which blunted approaches. But though difficult to reach, it was close enough to New York City, about twenty-five miles away on an east-west line, to permit Washington to watch his enemy. New Brunswick and Amboy were about the same distance, so Morristown was not isolated and the army there could not be cut off, for escape to the west through passes in the hills was available. And should Howe push out from New York against Philadelphia, he could be struck on his flanks. The army at Morristown could also hit Howe if he went up the Hudson Valley.

Within two months the army had dwindled to such a size that it could not have harassed anyone. Those troops -- probably around a thousand in all -- who had accepted a ten-dollar bounty at Trenton in return for six weeks' service included some who-did not keep the bargain once the enthusiasm of victory wore off. Others went home in early February, and by March the army numbered less than three thousand men. As usual, recruiting proved a difficult business even though Congress had

____________________

1 | Ward, I, 319-20; Freeman, |

authorized the raising of eighty-eight battalions hard on the heels of the disaster on Long Island the previous August. In December it had added eleven battalions of infantry to the authorization besides supporting artillery, engineers, and 3000 cavalry.

2

An army-on-paper is rather ineffective in the field. Getting the men into camp taxed the army recruiters' skill, especially since the bounties they could pay frequently were exceeded by those of the states raising militia. Washington tried persuasion on those states, explaining the effects of their practices on his army, and when that failed resorted to threats -- as, for example, when he told the governor of Rhode Island that if his state did not reduce the pay it offered, it should not count on any "extraordinary attention" from the Continental army. Persuasion and the threats paid off: by early May, as the hills around Morristown turned green, the battalions Congress had authorized began to take form. Before the end of the month the army had reached almost 9000 effectives -- forty-three battalions -- and they could be armed, for muskets, powder, and clothing had arrived from a France still cautiously watching the struggle and surreptitiously giving aid to the Americans.

3