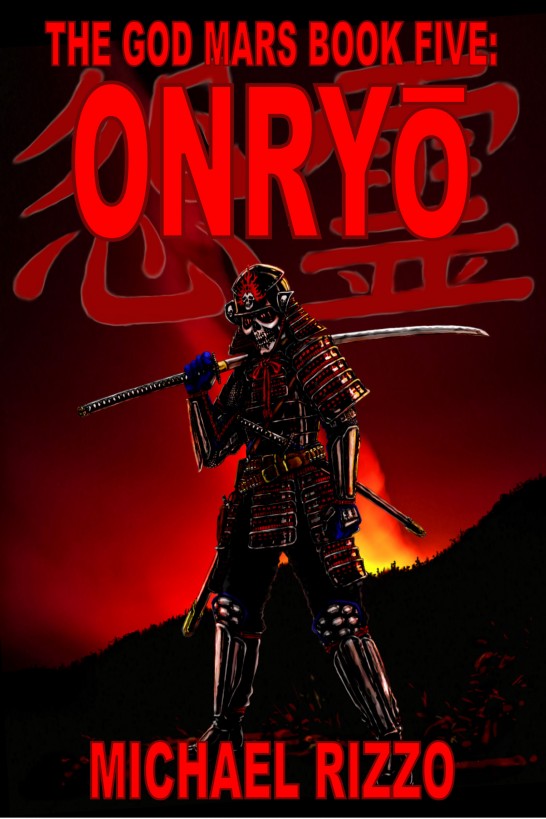

The God Mars Book Five: Onryo

Read The God Mars Book Five: Onryo Online

Authors: Michael Rizzo

Tags: #ghosts, #mars, #gods, #war, #nanotechnology, #heroes, #immortality, #warriors, #cultures, #superhuman

Book Five: Onryō

By Michael Rizzo

Copyright 2015 by Michael Rizzo

Smashwords Edition

Smashwords Edition, License

Notes

This ebook is licensed

for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or

given away to other peo

ple. If

you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading

this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your

use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your

own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this

author.

Part One: Dead Men Tell Tales

Chapter 5: Dead Man’s Memories

Chapter 6: Return of the Reaper

Part Two: Time of Death

Chapter 6: The Battle of Katar

Chapter 7: Fates Worse Than Death

Epilogue: The Importance of Ritual

Chapter 1: The Invisible City

From the Diary of Jonathan Drake:

“

Abu Abbas of the Northeast Melas Nomads, tell

your life.

”

The deep commanding voice of the War King of Katar

booms in the massive cut stone and rammed-earth chamber.

As bidden, my father steps up to the Speaker’s

Podium, standing directly under the circle of open sky that is the

apex of the Oculus dome. After a brief moment of silence to finish

gathering his thoughts, he looks out at our fantastic audience as

if he can make eye contact with every one of them. He takes a last

deep breath through his mask, and then loosens it to hang over his

chin so that he can be heard better, relying on the passive oxygen

bleed to keep him from getting light-headed in the thin but

actually breathable air here.

And then he honors the tradition of our hosts, as

strangers who come in peace are expected to: He tells the story of

his life, of our people.

“My name is Abu Abbas, son of Yusuf. I was born in

Twenty Sixty-Four by the old Earth calendar, a Standard Year after

my father brought his family to Mars. He was an engineer, and a

skilled near-vacuum welder. He worked hard out in the cold and what

was then one-percent atmosphere to construct Baraka Colony in the

belly of Melas Chasma. He helped build the first Holy Mosque on

this planet. Then he served as its Imam. He was a good man. A brave

man…”

His voice, as usual, is soothingly deep and rich, and

echoes off the walls of the great circular space, rivaling the War

King’s.

“I was not even a year old when the Apocalypse came,

but I remember pieces of it like an old nightmare. Alarms. People

running, panicking, faced—I realize now—with the unthinkable. My

father took us into the shelters, dug deep under the colony, but

the shock and the noise of the bomb through the bedrock of the

planet… By the will of God we were spared, some of us, because the

missile that was meant to sterilize our colony was knocked off

course before it detonated. A miracle… But the blast wave shattered

and crushed and burned the above-ground structures, the Mosque, all

of my father’s work.”

I notice something: Our hosts have all closed their

eyes and lowered their faces in unison, all the same, like a

ritual, just at the moment my father mentioned the nuclear

bombardment.

“Those of us that survived sheltered in place for as

long as we could. There was no word from the outside, no rescue, no

relief. The surface was too hot from all the fallout to go out and

explore, but within three months we had no choice, because our

water and air recyclers had begun to fail, and the Feed Line to the

colony had been cut by the blasts. We packed surface gear,

shelters, rations, and hiked in pressure suits for the nearest

intact Line. My father and the other engineers welded the first

Taps to draw what we needed: Oxygen. Water. Hydrogen fuel for our

heaters and cook stoves and generators. We made our home in the

open desert. And out of fear of those who had dropped bombs on us,

we painted our shelters to match the terrain, made these cloaks to

keep us warm and shield us from the sun’s radiation and hide us

when we moved. Unseen, they would believe us all to be dead, and

not send more bombs to finish the task. And so, by the mercy of

God, we lived.”

The story having passed the nuclear stage, our hosts

open their eyes and look up, look at my father with the same

dispassion they’ve universally shown since we were escorted through

their great Gate Wall, as if the coming of strangers is no more

than a routine annoyance.

As I stand here on the chamber floor with my too-few

surviving family and friends, my eyes can’t help but scan our

strange and amazing audience. The Oculus is easily big enough for

the several hundred citizens present, most of whom sit on the tiers

of benches that climb the walls all around us like stairs—I feel

like I’m standing in the bowl of a steep crater, the inner slopes

of which are made out of these incredible environmentally-adapted

human beings.

The adults are almost universally a full head taller

than we are, with long thin limbs and oversized rib cages. But

what’s most impressive when they gather in such numbers is their

homogenous color palate: The apparent civilians wear a variety of

simple hand-made clothes, all patterned with the same abstract rust

and green and ochre patterns as the armor of their warriors, as if

constant camouflage is as much a rule for them as it has been for

us. The effect of so many of them sitting so close together is that

they visually begin to blend into each other when they’re still.

Then when they all move—like they did to lower their gazes—it

almost makes me dizzy.

And even more striking than that is their dyed skin:

The ruddy mineral compound they use to protect themselves from

solar UV leaves a permanent rust red tint, under which can still be

seen a variety of ethnic tones ranging from pale to tan to dark.

It’s like I’m looking at them through crimson-tinted goggles.

They all sit and listen to the story of a stranger

(who must look as strange to them as they do to us) in perfect

polite disciplined silence. The only sound in the domed chamber

during my father’s pauses is the whisper-howl of wind across the

open circle of the single apex skylight—it produces a low tone that

makes me think of an ocarina, almost hypnotic. This gives the space

a palpable sense of sanctity.

Watching them, I decide to correct my initial

impression of these people: What I’m seeing is not a lack of

interest in the proceedings, but practiced, ingrained serenity. And

it’s being exercised in the face of what must certainly be

terrifying times.

The cold hardened stoicism is what I feel from their

Council of Kings, sitting at their curved stone table on the

chamber floor, facing the carved-stone Speaker’s Podium (and behind

it, the rest of us), symbolically forming a thin line between the

stranger and their people. Five pairs of eyes glare from faces that

could also have been cut from stone: full of hard experience, loss,

and difficult decisions. And here we are: one more difficult

decision. Or maybe not so difficult. Maybe they’ve already made up

their minds about us.

My father continues our history:

“We were not the only ones spared by God’s will, of

course. Soon we encountered more of our own, refugees from Uqba.

And a very few random others. But food was becoming scarce, and

there were those that were not interested in sharing. We risked

scavenging the ruins of the other Melas colonies, sometimes finding

precious rations, or useful supplies, medicine. Because of those

who would not share, we also began scavenging metal, making

weapons, because our precious few guns had precious little

ammunition, and when it was gone, all we would have left were poor

clubs. So we made knives and swords and spears, bows and crossbows,

and armor…”

He touches the lamellar on his breast, even though it

isn’t our manufacture—a fine gift from the Forge-Men (and an

impressive prize for a traveler to be wearing in this place). Since

they have let us keep our weapons—likely because they outnumber us

several-hundred-to-one—he also gestures to his prized revolver and

his Forge-made sword, then raises his cloaks to show them the rest

of his load: tools, canteens, breather gear, travel rations, med

kit, spare clothing; prayer rug and Holy Quran in their battered

protective cases…

“We wear all this metal, carry all this weight,

because we lost our colony centrifuges, and our parents wished us

to keep as much of the bone density and muscle of Earth-Gravity as

we could,” my father digresses as if he needs to explain, and

explain tactfully, since our hosts have obviously chosen the

opposite path: They’ve long-since embraced the conditions of this

world, strived to adapt to it as completely as possible, letting

their bodies develop unburdened in the .38 Gravity. Compared to

them, we’re almost as squat and thick-bodied as the Children of the

Forge.

“Even long after all hope of ever returning to Earth

had faded, we kept the practice. Tradition.”

He’s holding back. The real reason we keep Weight

Discipline is that my father—our Sharif and Imam, as his father

before him—reminds us that we were made in God’s image, and should

strive to stay so. Of course, saying that would likely sound like

an insult to our hosts, who have been gracious enough to let us

into their fortified homeland and not just kill us when we

approached their great defensive wall.

“As the years passed, we traveled and scavenged, and

sometimes encountered new groups. Our armor and weapons and

concealment tactics became essential to our survival and success.

To the southwest, Shinkyo Colony had become a hidden fortress,

defended by stealthy warriors. To the northwest, the City of

Industry, which was made to look like an abandoned ruin, was

protected by equally deadly soldiers, former Unmakers who still

call themselves Peace Keepers… I will let my good friend Lieutenant

Straker tell you of them in her own tale, as she is from

there.”

He nods to Jak Straker, who gives a polite but

clearly uncomfortable smile. Apparently even the power of a

Companion Blade does not overcome the inherent terror of public

speaking.

“To the northeast… From there came the Zodanga in

their crafty flyers and air ships, calling themselves ‘pirates’ and

raiding and killing for what they needed, striking from their

fortress in the Rim.

“We wandered, kept moving to avoid our enemies, and

divided our band into three factions, each taking a quarter of

Melas to seek their resources and fend off our mutual enemies, and

sometimes each other as need drove us to compete against former

brothers. Living and moving on the surface became easier as the air

thickened, but as it did, the scavenging became thin, the preserved

food began to run out, and our meager shelter hydroponic gardens

could not provide for all.

“But just as we were succumbing to malnutrition and

starvation, God again showed us His mercy. From the east came food:

A few brave travelers had managed trade with Tranquility in Western

Coprates—I will let my dear companion Ambassador Murphy tell you of

them. They brought us precious fresh and dried fruits, vegetables,

beans and grains. And so by God’s will we lived, had children and

grandchildren, occasionally fought with competitors and buried

loved ones for it.

“But then came the return of the Unmakers. And the

coming of the Shadowman.”

He punctuates these revelations with a dramatic

pause. I know our hosts have had their own intelligence of these

turns, some of it at tragic cost, so I expect this is the part of

the story that they’ve really been waiting to hear, far more than

my father’s life story as a testament to his—and our—character and

quality.