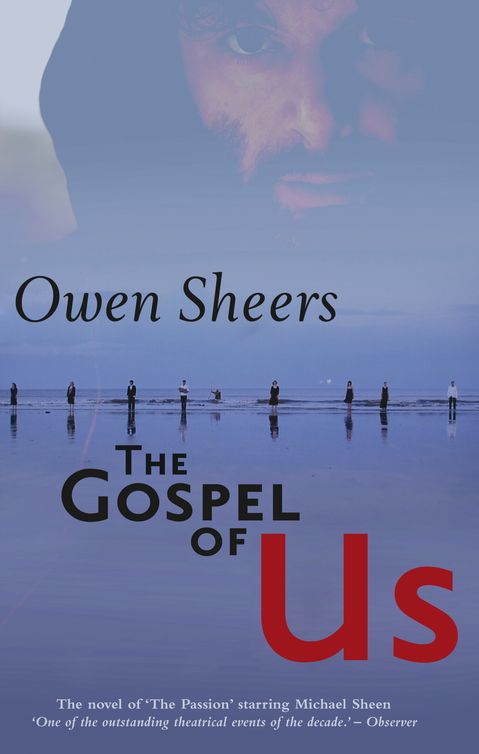

The Gospel of Us

Authors: Owen Sheers

For the teachers and listeners

It began with an actor, a producer and a poet sitting in a room talking about the seed of an idea. The actor was Michael Sheen, the producer was Lucy Davies of National Theatre Wales and I was the poet. NTW was planning its first year of site-specific productions. An ambitious schedule of a new production every month, all over Wales, hardly any performed in a theatre. Lucy had approached Michael to ask him what, if he were given the opportunity of working with this new national company, would he like to do? Michael told her he’d like to go back to Port Talbot, his hometown, and create a piece of contemporary theatre in response to the community Passion plays he’d once seen there as a teenager. It was at this point Lucy approached me about writing the script. She’d

read a few lines in one of my poems which seemed to echo a note of Michael’s idea, and she thought perhaps that might be true of the project as a whole too; that a poet, rather than a conventional playwright, might suit the nature of the production.

‘It’s not matter that matters,

or our thoughts and words

but the shadows they throw

against the lives of others.’

From

Shadow Man

At the time of that first meeting none of us knew what

The Passion

would be. We didn’t even know it would be called

The Passion

. What we did know, however, was

where

it would be, so that’s where we went next.

Like most people in South Wales I knew Port Talbot more as a view than a place, its constellation-lit steelworks a strangely seductive manifestation of Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’. I’d seen those steelworks as, like hundreds of thousands of others, I’d driven

along the stretch of M4 motorway that rises above the town. On the day of our visit, however, for the first time I walked through the town instead, guided by Michael and his memories of growing up there. With Lucy we walked along the front and down onto a slipway where we looked out at a saturation of sea disappearing towards a distant horizon. We walked along the wind-harried beach, tyre tracks coiling like ammonite fossils in the sand. We wandered between the graffitied pillars that support the M4 above a space of ground where a terrace of houses once stood. We went into a school, the shopping centre, a club. We stood in the middle of a roundabout and imagined a cross. And all the time we talked, so that by the time we left Port Talbot later that evening

The Passion

, a site-specific play performed over three days in Easter 2011, was already taking shape.

The final script and performance of

The Passion

was as much a response to Port Talbot as it was a response to the Christian tradition of the Passion plays once performed there. It was a piece of theatre

grown from a conversation with the town and its people. As we neared the performance date, however, we realised the play wouldn’t only be a result of that conversation, but would be continuing it too; in many guises, across many different forms. It already existed as a rumour in the town. Other people were becoming aware of it online, and would go on to follow the unfolding narrative via a website, Twitter and Facebook. The performance would be filmed, as a documentary, as a feature film and on thousands of personal cameras and phones. Like the gospels upon which the original Passion plays were based, the perspectives of witness were to be multiple.

It was within this varied narrative environment that Lucy asked me to write a synopsis of the play’s action, so an audience member who only caught some of the three-day performance might catch up with what had happened so far. In any other instance I may have written just that: a synopsis of plot and story. But somehow that didn’t seem right, or true to the voice of the project. Which is why I found myself

writing a new title for the same story at the top of the page in my notebook:

The Gospel of Us

What follows in this book is what I wrote next. The voice of a first-person narrator grown from and formed by Port Talbot; a fictional character I created and then let loose through the action of a play I’d written but not yet seen. NTW published the text in three pamphlets, each released on the morning of that day’s performance. As a writer this proved to be a unique experience. To sit in a pub and watch nine or ten people reading and talking about a fictional scene in which they themselves had just played a part. This was, though, typical of the nature of

The Passion

, and was always at the heart of what we’d hoped to create, even as far back as when Michael, Lucy and I first met in that room two years earlier. A maelstrom of an experience in which the audience would be both witness and participant; three days of performance where ideas

of place, history, fiction, theatre, life would all intersect within a single town before coming to a climax on a darkening roundabout beside the sea.

I realise I’m not someone you’d normally listen to; that usually you’d rather cross the street than risk hearing what I had to say – but you need to hear this.

Imagine me. My eyes hidden in the shadow of a hoodie, trackie bottoms, daps. The kid you recognise but never know; the kid with a dog slouch of a walk, a marble hardness in his eye. The kid who’s half kid, half man. Who’s stuck.

Don’t expect me to be speaking like this, do you? Well, I never used to. But he changed all that. And that’s why you need to hear this. Because this happened, and it happened here, to us. Believe me.

Whenever my bampa was down the social telling a

story, he’d pause before the best bits, lick his finger, touch it to his throat and then – so’s you could only just hear him – whisper, ‘God’shonesttruth now’. Then he’d carry on, making all those other men lean in over their pints and cans, listening.

Well, I’m licking my own finger now. And touching my throat. But it isn’t God’s Honest Truth what I’m going to tell you. It’s ours.

If it begins anywhere, then it’s with the man we came to call the Stranger. Still no one really knows who he was, or where he came from. But he came from somewhere and when he did, he came here, to the far end of the beach where the wind skates in across the bay to drive the dune grass crazy. That’s where I first saw him. I used to go down that part of the beach on and off. End of the day, or start of it, letting that wind and the sea-light bring me round from whatever high I’d ridden or drink I’d sunk myself in the night before. He never talked to me, didn’t even look at me. Just sat in this shelter he’d built, like a regular Crusoe, playing his guitar and singing to himself. At first I stayed well back, sitting

on one of the dunes behind him, or on the wall in front of the Naval. But after I’d seen him a few times, I began to move closer, and that’s when I heard what he was saying. And I wasn’t the only one either. Every time I went down there, there were more of us, all moving slowly closer to him each time. No one speaking. Everyone just listening. Not that he was speaking or singing to us. No. It was the sea he was talking to, or just above it anyway, where the sky looks like water, or the water like sky.

When the slate falls,

when the crowned head drops,

when the sail is hoisted,

the earth shall give them up.

From the fire beneath the cross

the treasure shall be released

and the dead shall live

and the living shall be heard

and the heard shall be freed

and the freer shall be dead.

What was hidden shall be shown.

What was silenced shall be said.

What was forgotten shall be known.

That’s how it went for a week. More people each day at dawn and dusk, under sun, rain and moon, and the Stranger singing his song to the sea. That’s how it went. Until the morning of the Arrival, when everything changed.

The town was getting ready to welcome the Company Man. ICU was sending him here to make an announcement, and the Council and the Mayor had been getting themselves in a right twist about it for months. They wanted to show him a proper welcome, show him they had things handled down here, under control. That there was no need to go back to the bad old days when things had all got so bloody heavy-handed.

The preparations had been building for a week by then – platforms, welcome banners, bands practising flourishes and anthems. As the sun came up and I took my regular place in the dunes at the Stranger’s

camp, I could still hear the carpenters’ hammers echoing up the beach. I’d been up all night, dropped a few tabs and I wanted to take some time out, hear him sing again, before I went home and tried to sleep. But as I sat down I saw something was different. The Stranger’s song had changed, and he wasn’t singing to the sea anymore but towards the Swansea end of the beach, towards the dunes and the grasses there.

He is come,

the empty vessel that will fill,

the one voice made of many

the man-key who will turn

the one who will release them

and heal us with his hearing

who will make us remember

what we’ll never forget.

He is come.

All of us there, the crowd around his camp, we all looked to where the Stranger looked. Looked at the

empty beach, his voice and the fizz of the waves filling our ears. There were more of us than usual; new faces had joined the regulars. Some had come because they’d been told about the Stranger; others were just passing. An early surfer, his wetsuit half peeled and his board under his arm; a woman walking her dog; a jogger, damp sand sprayed up the backs of his legs. All of us, motionless, looking down the empty beach.

Then, suddenly, the beach wasn’t empty any more. There was a man. A man standing on a dune looking back at us; beard to his throat, wild hair stuck with bracken, clothes ragged and smeared.

When the Stranger saw him he stood up. The man was staring at him, couldn’t take his eyes off him, like he was trying to remember where he’d seen him before. The Stranger though, he was as cool as you like, like this was all arranged. Like this was what he’d been waiting for.

For a minute or so they just carried on looking at each other. Then, moving awkwardly, like a man much older than he was, the Newcomer began

walking down the dunes. When he got to him, the Stranger took him by the hand and led him down to the water’s edge. Once there, the Stranger began undressing him, just started unpeeling the Newcomer right there and then on the beach. His skin was as white as a strip light. Dirty hands like gloves, a dove’s collar of grime round his neck. Then the Stranger undressed too, leaving his clothes in a pile on the sand. And then they walked in, walked right on into the sea.

So, there they are, these two men, staring into each other’s eyes, the foam of the waves washing round their waists, and all of us watching them. Eventually the Stranger breaks his stare and starts washing the Newcomer, scooping up handfuls of seawater over his arms and shoulders. All of us, meanwhile, begin walking down towards them. Which is when I see the two women and the little girl.

They were still far down the beach when I saw them, not as far as the preparations for the Company Man, but far enough so it was just their white nightdresses that shone out. I couldn’t see their faces, but

I could tell their ages from the way they moved. An old woman on the left, a little girl, no more than nine or ten in the middle, then a younger woman on the right. They were walking towards us, holding hands. And they weren’t the only ones either, because coming off the road was a chain of old men and women, shuffling down the road and up onto the beach. From the Home they were, Ysbryd Y Mor, in dressing gowns, slippers, nightdresses and pyjamas. Some of them couldn’t have set foot outside for years, but there they were in the dawn light, the three cranes of the harbour standing to attention behind them, the whole town stirring from under the shadow of the mountain and these old folks, up and about and coming down to the sea to join in the fun.

By the time they reached us the crowd had formed a big semi-circle at the water’s edge, everyone watching the Stranger and the Newcomer. The old folks joined us, then so did the two women and the little girl, coming right into the middle of the semi-circle, silent as you like, to stand and watch

what would happened next. Which was this.

Slowly, the Stranger took the back of the Newcomer’s head in the palm of his hand, like a mother might a baby’s. With his other he embraced him, supporting him at his back like a movie star preparing to dip his lady for a kiss. Sundogs lit up the sea in patches behind them; the wind blew spray up into the early air and the gulls circled above, calling. For a second, everything was still, the two of them never taking their eyes off each other’s face. Then, suddenly, it wasn’t. Using all his strength, as if he wanted to get rid of him forever, the Stranger pushed the Newcomer, eyes still open, under the water.

He was under for a moment, and for a life.

When he surfaced again the breath he took was like his first and when he lifted his head and looked at us, it was like he’d never seen people before.

The Stranger led him back onto the beach after that, where he dressed him not in the crazy mix of clothes he’d arrived in, but clothes given to him from the crowd. The surfer handed him his jeans; a young lad his blue hoodie; the woman with her dog,

her socks. And the Stranger dressed him in them. Dressed him as tenderly as a lover, or a son dressing his father.

Then the dance began. I don’t know who started it, where the first hip swayed or the first foot tapped, but out of nowhere, people were dancing. The old folks from the home, men, women, the surfer, the jogger, all of them started dancing around the Stranger and the Newcomer, dancing in a closing circle that swept them up and took them on down the beach. Everyone, dancing at dawn. Everyone, that is, except the two women and the little girl. They didn’t dance. They just looked, standing in a line in their white nightdresses, hands held, watching. And I didn’t dance either. My head was spinning, my body was light and my heart was pounding. I didn’t understand anything and yet it had all made sense, as if it was all meant to happen. Like the coming of the tide or the setting of the sun. It was natural. But it was also too much for me, so I hung back while the old folks and the Stranger and the Newcomer danced their way on down the beach, and

the two women and the little girl watched, and the town beyond started to wake, unaware of the storm approaching it.

The next time I saw the Stranger and the Newcomer it wasn’t in person, but on paper. Along with most of the town I’d gone to the welcoming preparations for the Company Man down at the other end of the beach. There isn’t much love for ICU here, nearly every lad with a pocket full of plectrums has written some kind of a song having a go at them. But they were in charge back then so there was a three-line whip from the Council to turn up. And to be honest, sod all else normally happens, so of course we were all going to have a look-see, weren’t we? Besides, the closest people like the Company Man usually ever get to us is when they drive over the Passover, when a few wisps of smoke from our fires might brush against their tyres or whiff in through the fans on their dashboards. So, yes, if he’d come to talk, then we were going to listen.

Anyway, so there I was, milling around the crowd, looking for a loose pocket to pick, when I saw the

Stranger and the Newcomer again. At first I didn’t know it was them. There was just this worried-looking woman, all frowns and concern, bloodshot eyes from crying, suddenly there in front of me shoving a piece of paper into my hand. ‘Have you seen him? My son?’ she was saying. ‘Have you seen him?’ Not that she stayed for an answer. Didn’t pause even – went straight on to the next person, pushing another piece of paper on them, and then the next, and the next. There were two lads with her, trailing behind and looking equally concerned, but more for her than for the son she was asking about.

I looked down at the paper. MISSING, it said in big letters at the top, FOR FORTY DAYS AND FORTY NIGHTS. Then there was a photo, blurred and grainy, from CCTV from the looks of it – two men walking through the shopping centre, deep in conversation. One of them with his head circled and brighter than the other. Underneath the photograph it said:

Last seen with this man in Aberafan Shopping Centre. Local teacher, missing for over a month. If you have any

information please contact his family on 07927 935215

.

I looked at the photograph again. And that’s when I saw it was them. The Stranger and the Newcomer. The Stranger didn’t look too different. Had the same beard and everything. But the Newcomer, this teacher, well, he looked like a stranger to himself. Clean shaven, hair slicked back, smart jacket and shoes. But it was him; I was sure of it. Something in the eyes, in the way he was looking at the Stranger. It was him.

I looked up for the woman and her two sons. But the beach was packed now, and getting busier every second. So I turned back towards the town and, elbowing and shoving and squeezing between bags and bodies, made my way up to the steps by the slipway. Get some height I thought, see if I can’t see her down there, making her own way through the crowd.

The beach was a crazy sight from up there. Thousands of people spread over the sand, right down to the water. Lines of local police in front of the slipway,

welcome banners snapping and humming in the breeze, bands practising on the steps, the Mayor and the Councillors being shown where to stand so they could best lick the Company Man’s arse. And that was just the obvious stuff. When I looked harder other, more secret stories made themselves known.

The teacher’s mother wasn’t the only person handing out pieces of paper. The local Resistance boys were at it too. Not as publicly of course, but they were there, weaving through the crowd, slipping flyers into pockets, pulling people to one side for a whisper in the ear or to press a folded pamphlet into a palm. Wasn’t like they were going to miss a chance like this. They probably knew what the Company Man was coming to speak about already, and somehow I doubt what was on those flyers was a letter of support.

Further off I saw Simon my old music teacher from school, coaching some of the choirs. Old Alfie was there too, making a rare appearance from his house on Llewellyn Street. And Maggie as well, trying it on with the men, bold as brass, right in

front of their wives sometimes, sniffing after any opportunity she might get to earn a few quid round the back of one of them stalls. Seemed like the whole town was out that day, buzzed up with anticipation. But no sign of the teacher’s mother any more. And no sign of him, either.

Yet.