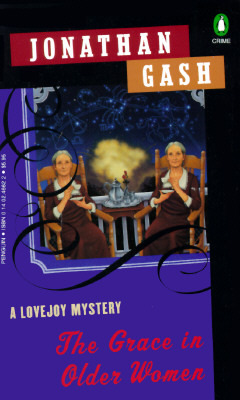

The Grace in Older Women

Read The Grace in Older Women Online

Authors: Jonathan Gash

For Sarah Kate, Jack and Nooni, and for Matthew John, with love

from Volzania

Thanks Susan

To Kuan Ti, ancient Chinese god of war, pawnshops, and antique

dealers,

this book is humbly dedicated

Lovejoy

1

'Will they see us?' she whispered.

My blood went cold in panic. 'Who? Who?'

'Anybody.'

Who else? She gripped my hand. The forest was silent. Not a bird

cheeped, not a leaf crackled. 'We're alone, for God's sake!' I tried to make it

sound romantic. 'Er, dwoorlink.' I'd nearly called her Mary. She was Beth.

We slithered down the slope, leaves skittering.

'I haven't got long,' she whispered.

Women always worry about what comes next. It would have narked me,

but I was desperate for her. We sat, lay, then sprawled. Her husband was due

back at twenty past.

Her breasts were cool. Odd, that. On the hottest days, women's

breasts are cool. The sun just made it through the trees, dappling the

undergrowth. The moans started so loud that I tried to cover her mouth with my

hand, but she shook her face free and whispered that it was me, not her, making

all the noise. It was beautiful as ever, the most wonderous ecstasy mankind can

imagine. I loved her from the bottom of my heart, in the most perfect of all

unions.

Afterwards we dozed in that post-lust slumber. I was awakened by

her licking my mouth and eyes, asking if she'd been good. That's another

puzzle. They always worry, as if there are grades of bliss. I told her she was

superb. 'You were paradise.'

'Honestly, Lovejoy?' she said.

She was thrilled. I was thrilled she was thrilled, because it was

touch and go whether she'd sell me her Bilston enamels that I craved. I know

love, if nothing else.

'Darling,' she said mistily, then gathered her clothes to her

exquisite breasts in alarm. 'Shhh! Lovejoy! What's that?'

'Squirrel?' Did squirrels make a noise, growl or something?

‘It was a click.' She started flinging on her clothes.

Admiringly, I watched. Women's clothes are complicated, and they

manage them with grace.

'A twig,' I explained. I’m good at nature. It's a beaver.'

She darted frantic looks for marauding husbands or, even worse,

neighbours.

'Stupid!' she hissed. 'You don't get beavers here! Get dressed!

Someone's coming!'

So? If people had any decency at all they'd politely ignore us.

There wasn't anybody, of course. Women are scared witless of gossip. In three

seconds flat I was my usual scruffy self: crumpled trousers, holed socks, shoes

soled courtesy of Kellogg's cardboard, shirt with one perilous button, jacket

frayed at cuff and hem.

'I mustn't be late, Lovejoy.'

'Right, right.' Women are always late, even if the clock says

they're not. Dreading being late's their thing.

We tiptoed from the scene, gradually walking further and further

apart as we approached the path from Fordingham. By the time we reached the old

church we were clearly strangers, coincidentally strolling through the woods on

a bright warm day. The only giveaway was Beth brushing imaginary leaves from

her skirt every two yards. She reached the ancient churchyard where she'd

parked her motor, drove off without a word. It's no good being indignant, but

you can see what I mean. They always worry about what comes next, when the

present moment is the danger. I should have remembered that.

At the old pond I paused. The path across Lofthouse's fields was

clear of cattle. Nobody, except a girl coming from round the side of our

disused church. Smart, colourful in a bright peach frock. I was tempted to try

to walk with her, but she angled away towards the distant manor house. Oh,

well. But the footpath wasn't littered with outraged bulls, and the chance was

too good to miss.

In my ignorance I took it as a good omen, and plodded on towards

the village at peace with the world, thinking of Bilston enamels. I'd only met

Beth a week since, when she'd talked to the Village Society on 'Small Antiques

for the Home'. I'd gone along for a laugh, and been stunned when she'd shown, voice

wobbling nervously, a genuine Bilston. My chest had thrummed and gonged so hard

I'd almost collapsed in my chair. She'd left before I could shove through

during the wine-and-wad session afterwards.

The day after, I'd caught her at the supermarket, having followed

her. I made stilted conversation, I'd enjoyed her talk, antiques being me and

all that.

'Oh,

you're

Lovejoy!'

she'd said, colouring. 'I've heard about you from - ah. I didn't realize I was

speaking to the learned.'

'Me?' I laughed a gay throwaway laugh. 'No, just interested.'

And went on from there: the glimpse of my deep inner yearning,

honest admiration for her showing through, letting myself be drawn in despite

my determined resistance to her allure. She'd invited me to her bungalow, shown

me the Bilstons, fascinated when I all but keeled over at being so near genuine

antiques. She'd got a mind-boggling eleven.

Don't laugh, because enamelling is one of the most difficult arts

in history. Think a minute, and it's obvious why it must be so hard to do.

Painting some metal with an opaque glass colour and heating it sounds easy, but

you just try it. Never mind that the ancient Etruscans, the Chinese, even the

early Britons all had a go. Alfred the Great's lovely Somersetshire jewel - he

ordered it in AD 887 -looks a cinch, but the fake copy I once did drove me

insane, took five months, and cost burnt fingers, eight metal splinters, and a

fortune in materials. Adding insult, a charity woman talked me out of it for

the Alder Hey Children's Hospital, which only goes to show how cruel they can

be. And if you're going to try it, remember what the old enamellers used to

preach before the spray method came in: you can't do it on big flat areas, only

on curved - hence their liking for enamel miniatures - and the classic maxim

that

every speck of dust leaves a hole in

the colour.

Bilston was the enamel Mecca. Once, collectors only thought

Battersea. Now, the world is obsessed with Bilston and greedy for its enamelled

plaques on silver and gold. If you too are crazy you should learn the Bilston

colours, like they used a near peagreen from 1759 on. But the one colour that

sends collectors demented is the famous 'English pink', as Continentals named

the elusive, gentle, semi-rose hue that first saw light about 1785 and blows

your mind.

Beth's small gold-mounted pendant of flowers and leaves had it,

the chrome-tin complex, brilliant as the day it was made. Lovely, lovely. It

brought tears to my eyes, just thinking of how unfair life was, giving pristine

jewels to an undeserving lass like Beth when they should have been mine.

Almost overcome, I reached my cottage in its overgrown garden. An

envelope was on the bare flagstone in the porch. I brewed up, threw the letter

aside. I recognized the handwriting. It would be the same old dear from

Fenstone Old Rectory saying the same old thing:

Dear Sir,

Would you

be able, for a small consideration, to speak with our

parson

concerning a fund-raising matter? I have been

recommended to you by a person of your

acquaintanceship,

namely

Mr. Saughton Joyceson of Peckfold, Hertfordshire, who

testifies to your honesty and integrity, and to

your concern for

worthwhile

Causes.

Thanking

you in anticipation,

Yours

faithfully,

Juliana

Witherspoon (Miss)

It was the tenth begging letter I'd received from her in a

fortnight. Church fund-raising, when I was broke? One odd thing, though. I

retrieved the envelope. No postage stamp, no frank, so delivered in person. I'd

have to watch out. If the geriatric herself had come to haunt the village's leafy

lanes I'd better treat her as yet another predator, among bailiffs and servers

of summonses.

Tea up. I took it out and sat on my low wall, which I'd finish one

day, and swigged it with some jam and bread, but the robin and those little

dipping brown birds came cadging so I only got half. I'd no more nuts for the

bluetits. Let them go without for once, serve the thieving little swine right.

They'd had my milk twice this week. They rip the foil cap so the bottles fill

with rain. I get diluted rainwater while they get the cream. Life's just one

damned thing after another.

2

Things are never what they seem. And I include every single thing.

I could give you a million proofs, but Jox proves it best.

For a while I hung about the cottage. Its peace and tranquillity

got me down so I hitch-hiked to town. There's a tradition in the village that

anybody waiting by the chapel bus stop deserves a lift, but I don't trust to

fortune. Women give me a lift if nobody's watching. Blokes only want to bully

me into some parish council or club or sell me a secondhand motor as dud as my

own. I always start walking.

Imagine my astonishment when a motor stopped. For a second I

rejoiced, but it was only Jox. I got in with misgivings.

'It didn't come off, Lovejoy.' Not even a good day, hello.

'How do, Jox. It didn't, eh?'

He groaned, slipped his motor into first and pulled away. 'I had

to hock my Jaguar.'

He

pawns one of his

three grand vehicles, so

I

must

sympathize? 'Hard luck, Jox.' I'm pathetic.

'This is my brother's.' He nodded soberly. 'Charges me hiring

fees. Tax, y'see.'

'Good heavens,' I said gravely, baffled.

There was more of this, all the way past St Peter's on North Hill.

I won't go on, because Jox is the loser. Note that definite article:

the

, not just any old loser. Champion

loser, is Jox. To realize the extent of his gift for catastrophe you have to

know his background. It is formidable, for Jox was born rich, handsome, gifted,

brilliant. He's only twenty-eight. He looks about ninety, on a good - meaning

not specially disastrous - day.

Born into a titled family that owned (past tense, for Jox's

calamitous skill is congenital) half of Lincolnshire, he went to famed schools,

was tutored by genuises, was an international athelete at swimming, hurdling

and other sports of mind-bending dullness, gained a double first (whatever that

is) at Cambridge University, married spectacularly some glamorous titled lass,

got a spectacular divorce . . . Couldn't fail, right?

Wrong. Jox became an antique dealer.

With a residue of gelt, Jox got a small antique shop not far from

Dragonsdale, between here and Fenstone. Rural to the point of somnolence. He

could have done well - tourists on the way to John Constable's village,

Gainsborough's house, pilgrims to Walsingham, all that. But Jox is jinxed. His

fortunes plummeted, everything he touched turning to gunge. Like everybody who

wants to 'settle down and run a small antique shop', he bought wrong, bid for

fakes at every auction in the Eastern Hundreds, accumulated more dross than a

town dump. And spent, and spent.

Until he was broke.

Then he borrowed, and spent. Finally getting the hint that the

antiques trade was grimsville, Jox opened a small restaurant. It failed,

gastroenteritis being what it is. His wildlife scheme ended when the local fox

hunt found some ancient parchment that barred him. Those mediaeval monks had

simply guessed Jox was on his way.

His real estate firm died when property developments crashed on

account of a series of ancient footpaths somebody discovered. See what I mean?

Folk who have everything just don't have it. The latest thing was this

orchestra.

'Nobody wanted to play, eh, Jox?' I guessed shrewdly.

He almost wept, cursed at a little lad on a bicycle and honked his

horn. Not a lot of patience, Jox.

‘Play?' he cried, utter grief. 'It would have been superb! Like

they did at Stoke-by-Nayland, that occasional choir and orchestra! Imagine

playing in Fenstone's old St Edmund's Church. Like the Makings at Snape - a

musical Mecca!'

'Ta for the lift, Jox.' I tried to get out. We'd reached Benbow's

auction room. I was fed up with Jox.

'That bastard of a parson scuppered me, Lovejoy.' I swear tears

filled his eyes. Well, money does that.’

'Wouldn't lend his church?'

'Fenstone parish council refused.'

Tough, Jox.' I shook his hand off, made the pavement.

'It's that bloody village, Lovejoy. Ever since I set foot . . .' He

shouted for me to hold on. 'Oh, Love joy. A ceremony tomorrow night, okay?

Seven o'clock, the castle.'