The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire

Read The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire Online

Authors: John Freely

Tags: #History, #Biography

Table of Contents

Chapter 3 - The Conquest of Constantinople

Chapter 4 - Istanbul, Capital of the Ottoman Empire

Chapter 7 - The House of Felicity

Chapter 8 - A Renaissance Court in Istanbul

Chapter 9 - The Conquest of Negroponte

Chapter 10 - Victory over the White Sheep

Chapter 11 - Conquest of the Crimea and Albania

Chapter 12 - The Siege of Rhodes

Chapter 13 - The Capture of Otranto

Chapter 14 - Death of the Conqueror

Chapter 15 - The Sons of the Conqueror

Chapter 16 - The Tide of Conquest Turns

Chapter 17 - The Conqueror’s City

ALSO BY JOHN FREELY

The Lost Messiah: In Search of Sabbatei Sevi

This edition first published in the United States in 2009 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

Copyright © 2009 by John Freely

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

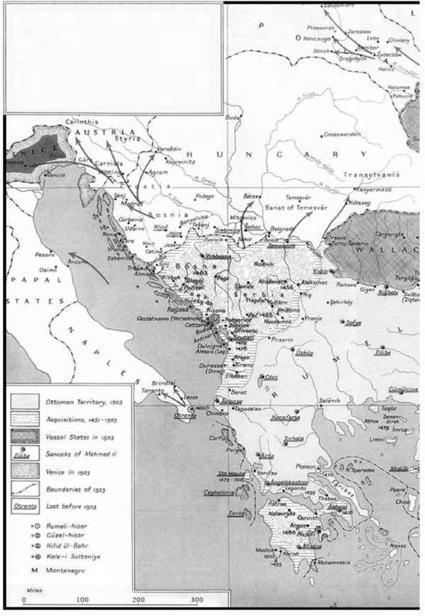

Map on p. xviii © Donald Edgar Pilcher,

An Historical Geography

of the Ottoman Empire,

Brill, Leiden, 1972. Map on p. xx © John Freely,

Istanbul: The Imperial City

, Penguin, London, 1996

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

eISBN : 978-1-590-20449-8

To Murat and Nina Köprülü

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the generous assistance I have received from the librarians at the American Research Institute in Turkey and Boğaziçi University in Istanbul. I would particularly like to thank Dr Anthony Greenwood, director of the American Research Institute in Turkey, Professor Taha Parla, director of the Boğaziçi University Library, and Hatice Ün, the assistant director. I am very grateful to Professor Heath Lowry of Princeton University and Steven Kinzer for reading my manuscript and making helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank my editor, Tatiana Wilde, who as always has been of great help to me in giving my manuscript its final form.

Turkish Spelling and Pronunciation

Throughout this book, modern Turkish spelling has been used for Turkish proper names and for things that are specifically Turkish, with a few exceptions for Turkish words that have made their way into English. Modern Turkish is rigorously logical and phonetic, and the few letters that are pronounced differently from how they are in English are indicated below. All letters have but a single sound, and none is totally silent. Turkish is very slightly accented, most often on the last syllable, but all syllables should be clearly and almost evenly accented.

Vowels are accentuated as in French or German: i.e. a as in father (the rarely used â sounds rather like ay), e as in met, i as in machine, o as in oh, u as in mute. In addition, there are three other vowels that do not occur in English: these are ı (undotted), pronounced as the u in but; ö, as in German or as the oy in annoy; and ü, as in German or as the ui in suit.

Consonants are pronounced as in English, except for the following:

c as j in jam: e.g. cami (mosque) = jahmy;

ç as ch in chat: e.g. çorba (soup) = chorba;

g as in get, never as in gem;

ğ is almost silent and tends to lengthen the preceding vowel; and

ş as in sugar: e.g. şeker (sugar) = sheker.

Prologue: Portrait of a Sultan

Half a lifetime ago, at the National Gallery in London, I first saw G entile Bellini’s portrait of the Turkish sultan Mehmet II, the Conqueror. I knew very little about the Conqueror at the time, for I had only recently moved to Istanbul, Greek Constantinople, the city Mehmet had conquered in 1453. Then in the last week of the twentieth century I saw the portrait again at an exhibition in Istanbul, where it had been painted in 1480, a year before the death of the Conqueror, who was known in his time as the Grand Turk, ruler of ‘the Glorious Empire of the Turks, the present Terrour of the World’.

When I examined Bellini’s painting in Istanbul I knew far more about Mehmet than I did when I first saw the portrait in London, for by then I had read and written much about him and his times and the city he had conquered. Mehmet’s capture of Constantinople in 1453 shocked all of Europe, for he had brought to an end the history of the Byzantine Empire, the medieval Christian continuation of the ancient Roman Empire, establishing in its place the Muslim empire of the Ottoman Turks, newly risen out of Asia.

Mehmet, the seventh of his line to rule the Ottoman Turks, was barely twenty-one when he conquered Constantinople, which thenceforth, under the name of Istanbul, became the capital of his empire. At the time the Ottoman Empire comprised north-western Asia Minor, where Osman Gazi, the first Ottoman ruler, had formed a tiny principality at the end of the thirteenth century, extending into the southern Balkans, which his successors in the next five generations took in their march of conquest.

During the thirty years of his reign, 1451-81, Mehmet extended the borders of his empire more than halfway across Asia Minor, while his armies in Europe penetrated as deep as Hungary and even established a foothold in the heel of Italy. Three popes called for crusades against Mehmet, whom Pope Pius II called ‘a venomous dragon’ whose ‘bloodthirsty hordes’ threatened Christendom.

The Ottoman Empire expanded even further under Mehmet’s immediate successors, particularly Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-66), whose realm encompassed all of south-eastern Europe and stretched through the Middle East, the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa. The Turks continued to occupy a large part of south-eastern Europe for four centuries after Mehmet’s death, and his dynasty ruled until 1923, when the Ottoman Empire gave way to the modern Republic of Turkey.

Today only 8 per cent of the land mass of Turkey is in Europe, separated from the Asian part of the country by the famous straits - the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus - the latter spanned by the urban mass of Istanbul, the only city in the world that stands astride two continents. Turkey’s foothold in Europe extends less than a hundred miles inland from the straits, the deepest penetration being at Edirne, where Mehmet was born in 1432. It was there that he began the meteoric career that led to the conquest of the city now known as Istanbul, where pilgrims still come to the tomb of the great hero known to the Turks as Fatih, or the Conqueror.

During the exhibition of Mehmet’s portrait in Istanbul a number of friends, both Turks and foreigners, remarked that it was a pity that there was no modern biography of the Conqueror other than that of Franz Babinger, a lengthy scholarly work published in 1953 and now somewhat outdated, and that there was a need for a new book on him and his times written for the general reader. And so that is what I have set out to do in this book, concentrating on the man himself rather than his conquests, though his brilliant military career will be described in detail along with its effect on Europe at the dawn of the Renaissance. As Lord Acton wrote: ‘Modern history begins under stress of the Ottoman conquest.’

My biography of Mehmet the Conqueror is focused on the historic conflict between western Europe and the Ottoman Empire, echoed today particularly in the case of Turkey, which is currently facing rejection in its attempt to join the European Union. The interaction between Christian West and Muslim East is usually seen as a clash of civilisations, as it is viewed in the so-called War on Terror. The original conflict that accompanied the rise of Islam brought Graeco-Islamic science to the West, beginning the modern scientific tradition. Mehmet’s conquest of Constantinople and his invasion of the Balkans and Italy brought Christian Europe face to face with a new Muslim empire that was actually a rich mixture of peoples, religions and languages, which is still evident today in the lands that were once part of the Ottoman Empire. As Edward Said wrote: ‘Partly because of empire, all cultures are involved in one another, none is single and pure, all are hybrid, heterogeneous, extraordinarily differentiated, and unmonolithic.’

Mehmet himself is an enigmatic figure, seen by the West as a cruel tyrant, whom Pope Nicholas V called the ‘son of Satan, perdition and death’, while being revered by the Turks as a great conqueror. My book will attempt to discover what kind of man posed for Bellini’s portrait, which I am looking at as I write these lines, wondering what was going through Mehmet’s mind as he sat there in his palace in Istanbul, having conquered an ancient Christian empire and established his own Muslim realm in the marchland between East and West, changing the world for ever.

OTTOMAN CONQUESTS, 1451 - 1503