The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities (88 page)

Authors: Matthew White

MOZAMBICAN CIVIL WAR

Death toll:

800,000

1

Rank:

55

Type:

ideological civil war

Broad dividing line:

Frelimo vs. Renamo

Time frame:

1975–92

Location and major state participant:

Mozambique

Minor state participant:

South Africa

Major non-state participant:

Renamo

Who usually gets the most blame:

Renamo

Another damn:

African civil war

M

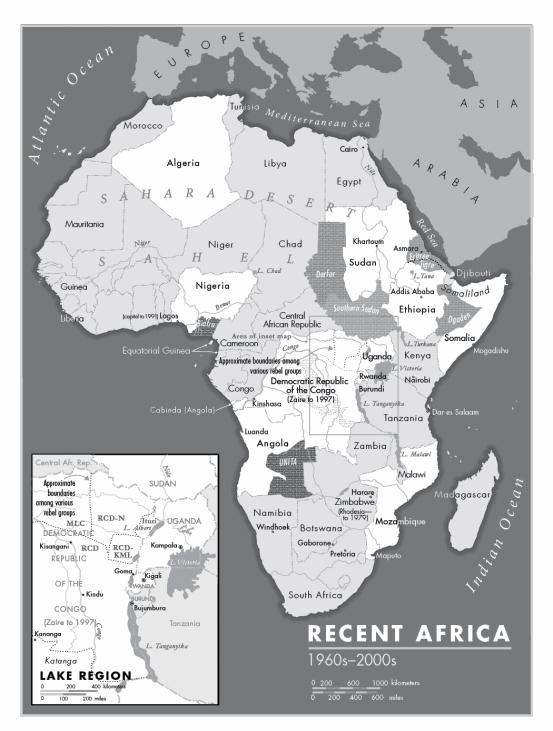

OST EUROPEANS DUMPED THEIR AFRICAN COLONIES BETWEEN 1955

and 1965, after which the last stubborn bastion of white rule in Africa was a bloc of lands in the south: the apartheid regimes of South Africa and Rhodesia nestled among the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique.

A broad coalition of rebels inside Portuguese East Africa organized the Front for Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) in 1962. They kept the pressure on the Portuguese government with a backwoods civil war for the next dozen years in the hopes that the imperialists would eventually give up and go home.

In 1974 a coup in Lisbon replaced the military dictatorship of Portugal with democrats, and the next year the new government granted independence to Portugal’s overseas colonies. Frelimo took control of Mozambique, after which the government declared itself Communist and cultivated support from the Soviets. Mozambique now became a haven and staging center for rebels fighting against the neighboring apartheid regimes.

In retaliation, Rhodesia and South Africa organized and armed outcasts, malcontents, and dissidents of all stripes as a new rebel organization, the Mozambique Resistance Movement (Renamo). Renamo had no unifying ideology or political goals other than the overthrow of Frelimo. Renamo’s leadership came from “traditional authorities down on their luck—petty chiefs,

curandeiros

(healers), witch doctors, spirit mediums—discarded as Frelimo laid the foundations for a pan-ethnic, socialist millennium. Magic played a useful part in keeping up Renamo’s fighting spirit. If its fighters rubbed their bodies with herbs, Frelimo’s bullets would ‘turn to water.’ ”

2

Rank-and-file support came from peasants who were forced by Frelimo to give up whatever small land they had and go to work on collective farms instead.

Renamo tried to destabilize the government by terrorizing civilians and damaging the economy. The rebels destroyed bridges and power plants, bringing the country to its knees. Even worse, their attacks against the general population were designed to maximize terror. Villagers often had their ears, lips, and noses cut away, and then were let loose as a warning to others. In 1988, a report for the U.S. State Department estimated that Renamo had blatantly murdered 100,000 people during the mid-1980s with raids, kidnappings, and random shootings. Their atrocities drove 1 million refugees into exile in other countries and left another 3.5 million displaced internally.

3

After years of war, the World Bank ranked Mozambique the poorest country in the world—not second or third, not “among the poorest,” but dead last.

4

Talks between the two sides began in 1990, and soon after that, Communist Russia and apartheid South Africa were swept into the dustbin of history.

*

This left Mozambique entirely on its own, no longer a pawn in larger struggles. Without sponsors to supply fresh ammunition, the two sides agreed to a cease-fire in 1992. Frelimo was confirmed in power by multiparty elections held in October 1994, while Renamo emerged as a legitimate opposition party with a surprising amount of support.

ANGLOCAN CIVIL WAR

Death toll:

500,000

1

Rank:

70

Type:

ideological civil war

Broad dividing line:

MPLA vs. UNITA

Time frame:

1975–94

Location and major state participant:

Angola

Minor state participants:

Cuba, South Africa

Major non-state participant:

UNITA

Who usually gets the most blame:

Jonas Savimbi

Another damn:

African civil war

Economic factors:

oil, diamonds

A

T FIRST GLANCE, THIS LOOKS LIKE THE EXACT SAME WAR AS THE ONE IN

Mozambique (see “Mozambican Civil War”) but with different names. Marxist guerrillas (in this case, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA) took over Angola after the Portuguese left in 1975, propped up by Soviet aid. South Africa supported an insurgency to keep them from meddling in South Africa’s affairs. The war fizzled out after their foreign sponsors collapsed. Just replace “Renamo” with “UNITA,” and we’ve got our chapter.

By the 1980s the rebels of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), led by the charismatic thug Jonas Savimbi, managed to carve out one-third of the country as their own autonomous enclave. In addition to South African aid, the United States, Ivory Coast, and Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (Congo) supported Savimbi’s fight against the MPLA government.

Unlike Mozambique, Angola has some obvious natural resources: diamonds and oil. The war kept production down, which drove prices up, so the few companies willing to risk getting caught in the crossfire earned nice profits. These companies generally had to maintain large private armies, which gave them a free hand to exploit the resources however they wanted, without competition or labor disputes. The diamond companies often shot down anyone they caught near company mines trying to dig diamonds for themselves. Even farmers hoeing their crops might be mistaken for illegal miners and shot.

2

The Angolan war sucked in more foreign troops than the average African conflict. Fifty thousand Cuban combat troops helped to prop up the MPLA,

3

while South African soldiers often crossed the border to hunt down insurgents from South Africa’s satellite country, Namibia. In 1978, at Cassinga in Angola, the South Africans massacred 600 Namibian refugees, claiming that the community harbored terrorists; however, most of them, maybe all of them, were noncombatants.

A cease-fire was negotiated in 1991, and multiparty elections were held the next year, but when Savimbi realized he was going to lose the election, he went back to fighting. Another year of conflict killed another 100,000 Angolans before Savimbi was offered a power-sharing agreement. He turned it down, but by then his former supporters had soured on him. UNITA was embargoed, and American President Bill Clinton finally recognized MPLA as the legitimate government in 1994. This is usually considered the official end of the war.

Without foreign sponsors, only diamond smuggling kept Savimbi financed, and he was pushed farther and farther away from the important parts of the country. He was finally killed in a fight with government forces in 2002, after which UNITA quieted down.