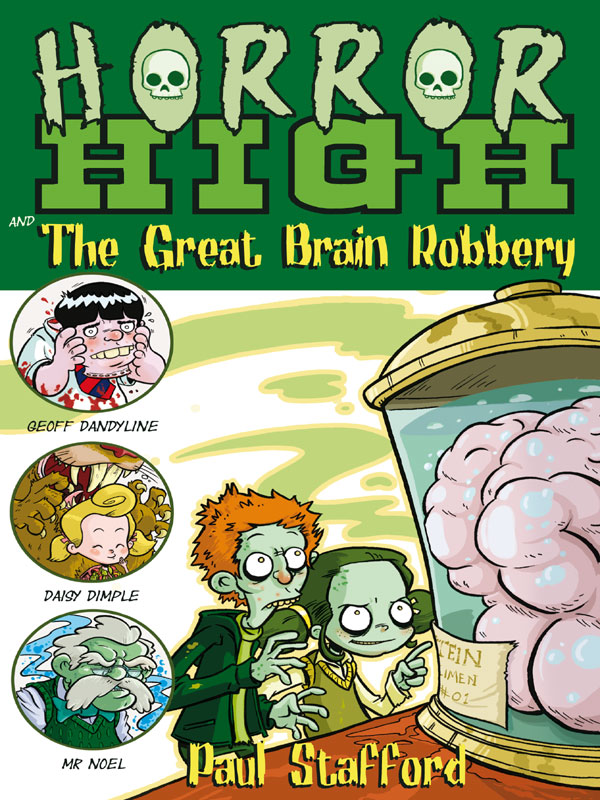

The Great Brain

Authors: Paul Stafford

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Horror High And The Great Brain Robbery

eISBN 9781742745787

A Random House book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First published by Random House Australia in 2006

Text copyright © Paul Stafford 2006

Illustration copyright © Douglas Holgate 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices

.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Stafford, Paul, 1966â.

The great brain robbery.

For children aged 9â14 years.

ISBN 978 1 74166 088 3..

I. Title. (Series: Horror High; 3).

A823.3

Cover illustration and design by Douglas Holgate

âMick Living-Dead. Mick Living-Dead?'

Mr Grimsweather peered up from the ancient leather-bound rollcall book and surveyed the class maliciously. âAnyone seen Mr Living-Dead?'

âHe's away, sir,' droned Geoff Dandyline. âReligious holiday.'

âReligious holiday,' hissed Grimsweather. âWhen's he back?'

âNot till next year, sir.'

âNext year!'

thundered Grimsweather. âIt's only October! What does he think this holiday is?'

âExtended zombie Christmas break, sir,' replied Dandyline, his grinning buckteeth reflecting the overhead fluro lights and nearly blinding the rest of the class in the process. âIt's a zombie thing.'

âZombie thing,' muttered Grimsweather. âI'll give him “zombie thing”. Extended zombie Christmas break. Why does it take zombies so long to celebrate Christmas?'

Dandyline grinned again and his monstrous teeth slid out his mouth like a beggar's bowl at a G8 Summit. âIt takes them a long time to warm up, sir â being dead and all. Zombie thing, sir.'

âShut up, Dandyline!'

A forbidding silence descended on the class.

âExtended zombie Christmas break,' Grimsweather mumbled angrily to himself. God, he couldn't wait to retire from this job; he was fed up making allowances for every dumbwit, dipso, freak-out student in

this kooky, bug-house school. He expelled a long breath of venomous gases.

Dandyline fancied he could see steam seeping out of the Rollcall Master's ears and squirmed in his seat with barely repressed delight â the old geezer was obviously close to losing it.

âBlast that zombie!' snapped Grimsweather. âMick Living-Dead better be back for my annual maths test or he's a dead man.'

âAlready been done, sir,' chipped Dandyline. âZombie thing.'

â

Shut up, Dandyline!

Do I have to tell you seven hundred times, or do you think you'll get the message with the standard six hundred and ninety-nine repeats?'

âNot sure, sir,' gaped the bucktoothed boy wonder (the âwonder' being how Horror High hadn't yet permanently terminated its most irritating scholar). âWhat was the question again?'

âThe question, Dandyline, was not a question at all. It was a statement, an order, a proclamation, a command â

shut up!

'

âThat's right, sir. Sorry, sir,' gushed Dandyline. âForgot, sir.' Then, grinning foolishly like an overgrown puppy with outsized fang implants, he added, âInteresting, though.'

Grimsweather stared hard at Dandyline, and the temptation to kill the boy on the spot with a blunt axe was obvious in the Rollcall Master's face. He was wrestling between this perfectly reasonable instinct and a bugging curiosity at just how dimwitted Dandyline's observation would be.

Curiosity won.

Softly, portentously, Grimsweather asked, â

What

exactly, Dandyline?'

âSorry, sir?' replied Dandyline.

âWhat exactly are you talking about?'

âI'm not talking, sir,' Dandyline grinned. âYou are.'

â

You

spoke, Dandyline,' Grimsweather seethed. âYou said, “interesting, though”. What, exactly, is “interesting, though”?'

âNot sure, sir,' replied Dandyline grinning. âYou, sir?'

Now Grimsweather lost it. He blew his top, shouting hard,

âNo!

Not me!

You

spoke.

You

said it. What did you mean by it? Tell me now, Dandyline, or you're dead.'

Dandyline fell to the floor, fawning pathetically at Grimsweather's cloven feet. âPlease, sir. No, sir. Don't kill me, sir. Mercy, sir. I'm too young to die, sir. Got my whole life in front of me, sir. '

âYour whole life? Blast you, Dandyline â you've got your whole life to drive me to lunacy with your brainless, inane jabberings.'

âPlease, sir. Sorry, sir. Tell me what to do, sir,' begged Dandyline. âHow can I change? Tell me what's wrong with my personality, sir. Tell me how to improve it so I won't infuriate you, sir.'

âWhat's

wrong

with your personality?' scoffed Grimsweather. âWe'd save a lot of time if I just listed what's

right

with it. But, if I was forced to evaluate your particularly warped, low-grade character, I'd say that you, Dandyline, are very close to a complete idiot.'

Dandyline smirked. âShould I move back, sir?'

Sparks shot from Grimsweather's eyes like volcanic eruptions, but the sound from his iniquitous black mouth was abnormally calm and satisfied. âI know how to improve your character, Dandyline. I know exactly how to remove your most irritating feature. It's easy, Dandyline. Guillotine. Lunchtime.'

The trouble started (as it often does in spongy, brain-degenerating stories like this) with a young zombie gent of staggeringly low intelligence (on a bad day even lower than yours, I'll warrant), an unwinnable, smarts-based bet with a brainiac school teacher and a poorly planned burglary that ended up causing grief to him, me, the school and everyone I know from your Teletubby-shaped aunt with

farcical facial hair to Queen Elizabeth's least favourite scone baker.

Everybody suffered.

And, just quietly, Albert Einstein paid pretty profoundly, too.

Â

It was Sunday dinner at the Living-Dead household and a fine sumptuous roast took pride of place at the table. Mr Living-Dead was carving the delicious smelling brain, and his razor-sharp carving knife slid through the glazed, golden brown tangle of cranium cables like it was a ball of rancid butter.

âCooked to a turn, dear,' commented Mr Living-Dead to his wife, his mouth watering in anticipation. âAs usual. I didn't just marry you for your good looks.'

Mrs Living-Dead smiled proudly. She was a drop-dead cook. Aside from the roast brain, there were honey-glazed eyeballs, stuffed ears, baked Adam's apples, cute little individual Yorkshire puddings made from freshly minced Yorkshiremen, and other highly palatable scran.

Delish.

Yet, despite this veritable feast, Mick was playing with his food, preoccupied. He was usually pretty good on the fang, but not tonight. Tonight he dawdled over his delectable dinner, body-swerving the bounteous banquet, vetoing the virtuous victuals.

âEat your greens, dear,' commanded Mrs Living-Dead. âThey'll make you smart.'

Fat chance, Mick's sister, Kim, thought to herself, grinning across the table. Mick was as thick as a telephone book â A-K and L-Z stacked together â and no amount of greens was going to alter that. But she didn't say it.

âYes, Mick, chop chop,' said Father sternly. âYour mother went to a great deal of trouble preparing those greens, so eat up.'

It was true. Mick's mum

had

gone to a great deal of effort with the dinner prep, spending more than two hours trapping, restraining, dismembering and cooking the Green family.

The Greens had scattered like steroid-enhanced Olympic athlete rabbits when cornered and took ages to catch, so they were obviously physically healthy â and probably organic. And they

were

good for the intelligence, or at least you'd assume so; Professor Green was a Nobel prizewinning scientist, Mrs Green was a nationally renowned mathematician with two doctorates, and the two Green kids were grade A students with awesome IQs and authentic nerd credentials.

Now here's the thing. Eating these Greens may have been highly beneficial for the rest of the Living-Dead family's intelligence, but it had sod-all effect on Mick. He could've eaten brains till the cows came home, had their afternoon snack, did their homework, then went outside and milked themselves, and it still wouldn't have helped a skerrick.

Eating brains did not give Mick brains. Eating the extra-smart Greens did not translate into loftier, more insightful thoughts leaping more rapidly across his

synapses. It did not result in Mick writing a treatise on the great apes of Borneo, or the problems facing barefoot Confucian scholars in the 21st century, or even the best way of robbing the un-robbable vending machines at deserted railway stations.

Eating brains had no effect at all on Mick. He remained fully and totally and super heaps thick, like an African boab tree in Nike shoes.

Listen. It's time to knock a tedious proverb on the head like a scabby old dog that refuses to be cured of scrofulous mange. That clichéd maxim âyou are what you eat' may apply to Kevin Bacon and Mr Potato Head, but it won't wash here. In fact, my own extensive research (twelve minutes in the local library â ten of them arguing with the librarian about

The Simpsons

, two spent kicking her bicycle chained up outside) proves beyond doubt that the you-are-what-you-eat adage is fully fallacious, seriously spurious and (resorting to schoolboy Latin) wrongus wrongus.

You are what you eat? Bogus. A hoax. Mick Living-Dead ate brains for every meal, but he wasn't brains. He ate them stir-fried; he ate them poached; he ate them in a totally tasty, creamy satay sauce; and he took sliced brain sandwiches to school, which had the advantages of not only being flavoursome and nutritious, but also possessing a low GI.

They tell me that's important.

But this is not a cookbook review or a lifestyle mag or even a Jamie Oliver blog â we are dealing in cold hard facts here, not soft old lady talk. The jury was back in and the truth was out: the effect on Mick of eating all those brains was precisely

nada

, measured on the most sensitive Spanish laboratory equipment available.

He was still dumber than twelve goats.

Nothing made Mick smarter, nothing worked, and therein lay the quandary: Mick didn't even know what âtherein' meant, and as for âquandary', forget about it.

But Mick knew this: he had a problem. As problems go, it was big. Big? Jeepers, it was huger than Oprah's chocolate bills.

See, Mick was locked into an exceedingly foolish bet with a teacher at Horror High that he appeared certain to lose. There didn't seem any obvious solution, and it'd have to be very obvious for Mick to grasp it. He couldn't wriggle out of the bet, and he sure couldn't win it.

He couldn't even kill himself. He was dead already.

Â

Monday morning, 11.15 a.m. Mick was at home now on extended zombie Christmas break, while the rest of the Horror High student suckers were still in school. Mick planned on staying here until he could nut his way through the problem. He'd eaten a lot of nuts, but there was no change as yet.

We'll bring you updates throughout the day.

Mick had conned Principal Skullwater into believing that it was essential he have extended leave from school due to the

complex religious ceremonies required at zombie Christmas-time, like drinking brain-nog under the mistletoe before eating the neighbour's Christmas tree, the neighbour's dog that wizzed on the Christmas tree and, finally, the neighbours.

The school admin staff fully fell for Mick's counterfeit excuse.

Horror High was especially sensitive to different cultures, traditions, weirdities and taboos, and the school authorities didn't dare question the zombie student. If zombie Christmas took three months to celebrate, so be it. They didn't want to be accused of cultural insensitivity and, in all truth, didn't give a coroner's curse if young Living-Dead was present at school or not.

Honestly, they didn't care if

anyone

turned up to school â they were paid a fee per student enrolled, and once the Department of Education After Death coughed up the loot and the teachers got their cut, that was all that concerned them. The students could rot in shallow graves for all the

teachers cared, so long as they didn't stink up the school and foul the vibe of the joint.

Maybe Horror High had gone all touchy-feely on cultural issues, but not all the teachers were soft and fuzzy in the head. Mr Noel, the science teacher, didn't believe that culture crap for a second. He didn't believe anything he hadn't seen under a microscope or through a telescope.

Mr Noel had a photographic memory, the power of instant recall and a phenomenal ability to whip out the answer to the most obscure trivia question straight from the deep, dark, evil recesses of his turgid black brain. He had whole rooms in his pad devoted to housing the dozens of trophies, cups and plaques he'd won in IQ competitions. He was even in the

Guinness Book of Records

for being the youngest-ever winner of

Horror Mastermind.

The pupils of Horror High hated Mr Noel with a zeal bordering on mania and nicknamed him Mr Know-All. Noel â Know-All. Get it? I know, it's lamer than a hobo cat. Any halfwit with a modicum of talent

could've really gone to town massacring a name like Mr Noel. Mr Noodle, Mr No-Brain, Mr Numbskull ⦠the list of clever deviations and mutilations could go on and on.

What did the face-ache students of Horror High come up with? Mr Know-All. It's embarrassing, but I assure you it's not my fault. I just get paid to report the facts and can only work with the material I'm given.

Mr Noel was not only superintelligent but also hardwired to be cynical and disbelieving of every excuse a student tried to peddle him. He was mostly right. In the case of Mick Living-Dead and his sham âextended zombie Christmas break', he was even rightier.

Rightier?

Whatever. He was bang on target. Mr Noel rang Mrs Living-Dead and questioned her extensively about any special elements of yuletide zombidity that required her fully unbright son to miss more school, thus rendering him even unbrightier.

That's how Mr Noel found out the truth. There was no such thing as an extended zombie Christmas.

According to Mrs Living-Dead, zombie folks celebrated Christmas the same way everyone else does â racking up monster debts buying crap, cheapo products that bust by Boxing Day and become toxic, unrecyclable landfill; maxing out their credit cards and using false names to borrow money off Mafia loan sharks; getting righteously quarrelsome and having fistfights with recalcitrant relatives; and eating enough junk food and sugar-based nasties to contract a robust and irreversible dose of type 2 diabetes.

Classy.

The Living-Deads celebrated a perfectly normal Christmas under standard Christmas protocols and certainly didn't practise anything odd or unsavoury or creepy that required Mick's extended absence from school starting in October.

Mrs Living-Dead spewed when she found out Mick was wagging school. She

may have died horribly twenty-three years ago when her bus exploded after a school excursion to the fireworks factory, but that didn't mean she undervalued education.

Au contraire

â which is French for âget to school, fool!' Time and again Mother Living-Dead had lectured Mick on the importance of schooling, the value of a good education, and the necessity of possessing, preening and pampering a good plump brain.

And not just for eating.

So next day Mick was back at school, a most unhappy chappy. He sat in his usual seat in the back row of Mr Noel's class pretending he was a turnip and did such a good impression that it would've taken a qualified greengrocer to spot the difference.

Now Mick didn't have any choice. He'd made his bet, and now he'd have to lie in it.