The Great Depression (2 page)

Read The Great Depression Online

Authors: Benjamin Roth,James Ledbetter,Daniel B. Roth

Dad’s therapy was to increase his workload. He continued practicing law until shortly before his death at the age of eighty-four. It was my great fortune to have been able to work side by side with him for more than twenty-eight years. He was my partner and mentor, and for that I am truly blessed. My parents never left Youngstown; it was their life.

During the time I worked so closely with Dad, he frequently discussed his diary. He looked forward to his retirement, when he planned to edit and publish it. Needless to say, he never retired. In 1978 he gave me the diary, consisting of fourteen handwritten notebooks that included entries from 1931 to 1978 (this volume ends in 1941, as the U.S. entry into World War II finally marked the end of the Depression). He expressed the hope that I would someday fulfill his wish, and I am very proud now to do so.

INTRODUCTION BY JAMES LEDBETTER

As a business editor, it’s not often that I read copy that gives me chills. But then again, October 2008 was a chilling time. In a few turbulent weeks, the nation’s economic mood had turned from apprehension to alarm, and giants were dropping all around with an ominous thud. One of the oldest and most prominent Wall Street firms, Lehman Brothers, had declared bankruptcy. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had to be taken into government receivership. AIG, a massive insurance company that had been acting like a highly leveraged bank, was bought out by the U.S. government in order to keep it from going under. The stock market, predictably but nonetheless cataclysmically, fell into a tailspin. In a six-week period from September 12 to October 27, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost more than 28 percent of its value, and it seemed entirely possible that it could fall much further.

During this time I received an e-mail from a Bill Roth at Citigroup, who told me that his grandfather Benjamin had kept a diary during the 1930s. He asked whether my fledgling Web site, The Big Money, online for barely a month, would be interested in publishing parts of the diary, and sent me some sample entries. My eye was drawn to this entry, dated July 30, 1931:

Magazines and newspapers are full of articles telling people to buy stocks, real estate etc. at present bargain prices. They say that times are sure to get better and that many big fortunes have been built this way. The trouble is that nobody has any money.

This was, of course, exactly what was being said in the media as I was reading it seventy-seven years later.

Another entry, dated August 9, 1931, reads:

Professional men have been hard hit by the depression. This is particularly true of doctors and dentists. Their overhead is high and collections are impossible. One doctor smoothed a dollar bill out on his desk the other day and said that was all the money he had taken in for a week.

I couldn’t stop my mind from jumping to a place I didn’t want it to go: Could we be headed for another Great Depression? Immediately, my defenses kicked in: No matter how many leading financial institutions were failing, we weren’t yet even in a declared recession. The government had a massive, unprecedented plan to save the banks. We had the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and a truly globalized economy, both powerful cushions against what happened in the early thirties. It couldn’t get that bad again—could it?

Yet the more I read the diary, the more I realized that no one living in the 1930s had known for certain that they were headed into a depression, either, until they were in its midst. And even then, they constantly scoured the landscape for signs of recovery, as we are doing today.

Benjamin Roth’s diary is a remarkable document, spanning fourteen handwritten volumes over five decades. In the early part of Roth’s professional career—the years before he began keeping this journal—his law practice grew as part of Youngstown’s historic boom. In 1900 the population of Youngstown was 45,000; by 1930 it was 170,000. That explosive growth was almost entirely the result of the rising steel industry. Youngstown possessed that magical combination necessary to produce steel: proximity to coal, limestone, and iron ore, plus capital, from the success of the iron industry in the late nineteenth century. Like the discovery of gold in California a half century before, the production of steel in Youngstown created a genuine boomtown, with ripple effects felt throughout the nation’s economy. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the steel industry in and around Youngstown was still embryonic; by 1927 it surpassed Pittsburgh as America’s largest steel-producing region.

A burgeoning town—with the need for increased housing and commercial activity—provided a young lawyer with plenty of business. While steelworkers themselves did not make high salaries, the managers of companies like Republic Steel (founded in 1899 and eventually the third-largest steel producer in America), Youngstown Sheet & Tube (founded in 1900, and for Roth the very barometer of local economic conditions), and Truscon Steel (a steel-door manufacturer that was purchased by Republic Steel but continued to do business under the name) prospered, and there was plenty of work to be done in property deeds, insurance, and similar commercial law work.

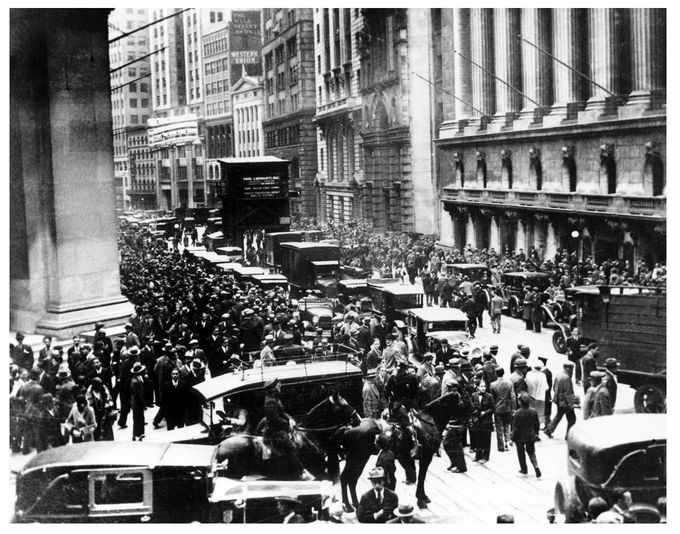

But not long after the stock market crash of October 1929, much of the region’s economic activity went into reverse, a process that Roth set out to understand as a witness at the center of the storm. To this day, historians, journalists, and economists continue to debate the exact forces that caused the worst economic downturn in American history. Like many of his contemporaries, Roth considered the 1929 stock market crash as the start of the Depression. Hordes of people who invested their life savings in the market were wiped out during the punishing “black days” of late October 1929. Stock values had begun to soften in September of that year, but on Thursday, October 24, mass selling caused the prices of the stocks to drop dramatically as brokers couldn’t find buyers to keep the stock value afloat. Investors’ panic continued on Monday, October 28. Millions more shares were traded, and stock prices continued to plummet. Then on Tuesday, October 29, the market completely collapsed: More than sixteen million shares traded and fifteen billion dollars in assets were lost. By mid-November the market had lost more than a third of its value.

While the gut-wrenching drama that played out in the stock market those October days made an indelible mark on Roth and many Americans, only about 2.5 percent of Americans actually owned stocks in 1929. Many subsequent historians see the crash as more of a catalyst for the Depression than its cause. Still, as economist Joseph Schumpeter put it, Americans of all walks of life “felt that the ground under their feet was giving way.” And the crash closed a frenetic era in American economic history, a period in which the stock market became the get-rich equivalent of the previous century’s gold rush. The notion that anyone with just fifteen dollars a week could become a millionaire by “playing the market on margin” pervaded American culture during the boom of the 1920s. This helps explain why Roth—who did not own stocks in the period covered by this diary—paid such close attention to the market. (In fact, we have cut many entries where closing stock prices were included with no context or commentary.) The seemingly endless rise in the stock market in the 1920s was exhilarating: Radio, newspapers, and even women’s magazines fostered and capitalized on this fascination by running stories daily on the market and ways to get rich on stock “tips.” As Roth ruefully noted later, many amateur investors had little to no knowledge about investment fundamentals, or even the specific health of the companies in which they invested; they were speculators, through and through. As the saying goes, they got theirs.

While the Great Crash didn’t cause instant mass unemployment or suddenly halt production lines, the events of October 1929 did expose structural problems in the 1920s boom economy. And the response was rapid; within a few months, new car registrations fell by almost a quarter from the September figure. As families, earning on average just two thousand dollars a year, cut back on their spending, manufacturers, stuck with overstock and expensive overhead, began to lay off workers. As the unemployed struggled with bills and consumed even less, more companies cut back on workers or even closed up shop. The unemployment rate skyrocketed. In 1929 the nonagricultural sector was about 1.5 million, or 3.2 percent unemployed. By 1930 it was 8.7 percent, or about 4 million. By 1931, when Roth started writing down his thoughts on the events around him, the jobless had nearly doubled to 15.9 percent, or 8 million.

Thousands of panicked Wall Street investors gathered on the streets outside the New York Exchange following the devastatingstock market collapse of 1929 that took place over the course of three days: Black Thursday, October 24; Black Monday,October 28; and Black Tuesday, October 29. Benjamin Roth pasted a clipping of this exact newspaper photo in his diary. (© Bettmann/CORBIS)

When Roth begins his “Notes” in 1931, he is conscious of a delineating crisis, one that obliterates the twenties-era intoxication forever (or so, I think, Roth would have believed). But he is not particularly scolding of the culture surrounding wealth or a bubble; rather, he seems dispassionately scientific in wanting to know how economic forces behave.

That he could summon such dispassion is itself remarkable, in an age that stoked passion into panic. More than in any economic downturn before or since, Americans during this era feared that the very pillars on which their society had always stood—democracy and free enterprise—could crumble and be replaced by something unrecognizable in the country’s history. This was hardly an idle fear: Germany had elected a Nazi government in 1933, largely in response to years of an imploded economy. Japan and Italy were being run by Fascists, and Stalin was in the process of turning the Soviet Union into a ruthless dictatorship. Historian Arnold J. Toynbee, who would go on to write a twelve-volume history of how civilizations rise and fall, wrote at the time, “In 1931, men and women all over the world were seriously contemplating and frankly discussing the possibility that the Western system of Society might break down and cease to work.”

And there was no shortage of advocates, on the Left or Right, who were eager to fill that void on American soil. The very first days of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency saw not only a reversal of the largely ineffective Hoover policies but an extension of federal control over the economy that Americans had never witnessed. Some on the Right attacked Roosevelt for dabbling in socialism, a position with which Roth seemed to sympathize in certain instances. Whether the various programs of the New Deal constituted socialism or partial socialism depends on one’s definition of that elastic term, and many historians take the position that even if Roosevelt had to curtail aspects of the free market, it was in order to save capitalism. But certainly the National Industrial Recovery Act, Social Security, the Agricultural Administration Act, Securities and Exchange Act, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation constituted government intervention into the minutiae of business activity that had no peacetime precedent in the United States. Furthermore, jobs programs in the Civil Works Administration, Works Progress Administration (WPA), and Civilian Conservation Corps resembled the types of government-sponsored employment that was often a feature of Socialist or Fascist governments. The fact that key parts of Roosevelt’s agenda were struck down as unconstitutional—which the legally trained Roth often pointed out—lends some credence to the idea that Roosevelt’s view of government and executive power tipped over into antidemocratic extremes.

Other books

Ghosts of Manila by James Hamilton-Paterson

The People in the Park by Margaree King Mitchell

A Reluctant Courtesan (Harem Masters #1) (Harem Masters Series) by Weaving, Nora

Broken Angel by Janet Adeyeye

Quin?s Shanghai Circus by Edward Whittemore

Capturing The Marshal's Heart (Escape From Texas) by Carroll-Bradd, Linda

The Big Miss: My Years Coaching Tiger Woods by Hank Haney

Red Fox by Karina Halle

Until Next Time by Dell, Justine

Lyon's Pride by Anne McCaffrey