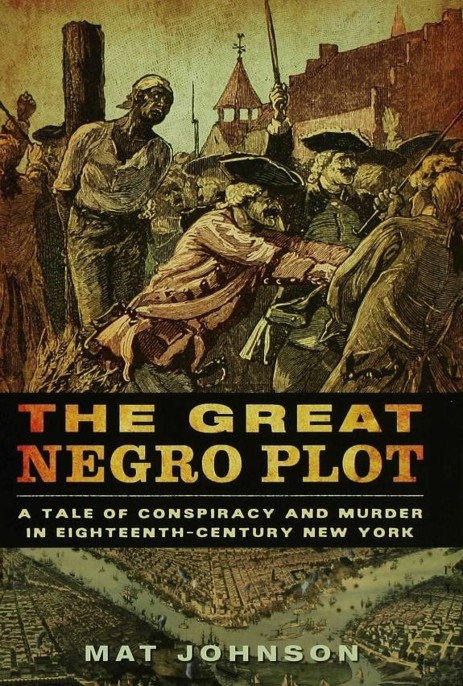

The Great Negro Plot

Read The Great Negro Plot Online

Authors: Mat Johnson

THE GREAT NEGRO PLOT

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Drop

Hunting in Harlem

THE GREAT

NEGRO PLOT

A TALE OF CONSPIRACY AND MURDER

IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK

MAT JOHNSON

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright © 2007 by Mat Johnson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, Mat.

The Great Negro Plot : a tale of conspiracy and murder in eighteenth-century New York/Mat Johnson.

p. cm.

eISBN-13: 978-1-59691-978-5

1. New York (NY.)—History—Conspiracy of 1741. 2. Slave insurrections—New York (State)—New York—History—18th century. 3. Conspiracies—New

York (State)—New York—history—18th century. 4. Murder—New York (State)—New York—History—18th century. 5. New York (NY.)—Race

relations—History—18th century. 6. New York (NY.)—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775. I. Title.

F128.4J64 2007

974.7'02—dc22

2006034162

First U.S. Edition 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Jasmin:

This is the world.

In estimating this singular event in our colonial history, the circumstances of the time should be daily considered, before

we too hastily condemn the bigotry and cruelty of our predecessors. The advantages of a liberal, indeed of the plainest education,

was the happy lot of very few. Intercourse between colonies and the mother country, and between province and province, was

very rare. Ignorance and illiberal prejudices universally prevailed. Their more favoured and enlightened posterity will, therefore,

draw the veil of filial affection over the involuntary errors of their forefathers, and emulating their simple virtues, endeavour

to transmit a brighter example to their successors.

—Anonymous, Introduction,

The New York Conspiracy,

1810 Edition

(New York: Southwick & Pelsue, April 5, 1810)

Perhaps it may not come forth

unseasonably

at this

juncture,

if the distractions occasioned by this

mystery of inequity,

may be thereby so revived in our memories, as to awaken us from that supine security, which again too generally prevails,

and put us upon our guard, lest the enemy should be yet within our doors.

—Daniel Horsmanden, original preface,

The New York Conspiracy

Contents

PROLOGUE: COLONY OF NEW YORK, 1712

" MARY BURTON, OF THE CITY OF NEW-YORK, SPINSTER"

FIRE, FIRE, SCORCH, SCORCH, A LITTLE, DAMN IT, BY AND BY

ENEMIES OF THEIR OWN HOUSEHOLD

"GOD DAMN ALL THE WHITE PEOPLE"

THE MONSTROUS INGRATITUDE OF THIS BLACK TRIBE

" I'VE BEEN A SLAVE LONG ENOUGH"

"HE SEEMED VERY LOATH TO DO IT"

PROLOGUE: COLONY OF NEW YORK, 1712

BEWARE THE AFRICANS, Koromantines and Pawpaws of the Akan-Asante, kidnapped from West African shores and brought to the ocean's

other side. Warriors, with anger and reason and nothing to lose, trained in the art of guerrilla tactics as part of their

rites of manhood. Fear them, Caucasians of the colonies, for they are men born into humanity, raised to be the inheritors

of society and not the beasts of it. They will lead and the rest of the slaves will follow, those other wretches whose own

belief in their equality was a rumor oft denied. Beware, colonists, for now it is your dying time. It had been two years since

the stolen members of their tribe had been transported to this cold, forest island. How long had they cached their stolen

weapons in the woods north of the village for this moment? How many outrages against their humanity had they endured solely

because they knew this time of retribution would come?

The rebel party was formed, ready to pour blood on the grass of Manhattan isle. Two were women—one joining her husband, the

other pregnant. Two were "Spanish Negroes," kidnapped off conquered Spanish vessels and enslaved on the basis that they were

brown, and you could do brown people like that, and there was good money in it. Tonight though, the brown ones would get to

pay back the debt. Fully committed, they now moved as one, their loyalty sworn by oath. Pledges insured by the literal collateral

of their eternal souls.

You get pain, you get so much pain, that there comes a time that you have to give it back again. Succored by anticipated revenge,

the chance to inflict blows in retaliation to those so casually given them. They had waited and now their time had come—two

hours past midnight, early one April morning in the year 1712.

April in New York is a curious time. Winter, it gets so damn cold, the polar wind tunneling down the Hudson, that by the end

you start to look at the brown naked trees and start to believe that they've got no green in them. You give up on life, because,

as March comes to a close, it's already become a thing of faith. Then April and the little buds start popping and you don't

just remember life, you believe in it. April in New York is the time of nature's revolution, where, after six months of frigid

death, the first daffodils finally scout the invasion of fauna.

The Africans knew to listen to the Earth, not dominate it. Shake off your freeze and come alive. April meant the promise of

warm months stretching beyond. A body could make good tracks in the time before October's winds shut things down once more.

Walk far enough north, run fast enough, and there was free country up there. Free living.

Later, when it was time to point fingers, the Caucasians said it was the pubs, wasn't it? Those black bastards, you get them

drinking, they lose their bloody minds. And maybe the smell of alcohol was among them, spirits swallowed and spilled in tribute

for the deed to go down. Maybe the Europeans just needed the rumors of drink to dismiss the event as a drunken moment of rage,

an anomaly for an otherwise docile breed of man. Peter the Doctor didn't need to swill Geneva to find his gumption, no indeed.

Peter was a free man, he'd tell you, the one free black among them, a man of knowledge, wise in the ways of the old land.

Come before him, this man of wisdom. Let him shake the powder on your head that will protect you from the powder that fuels

the colonists' guns. Believe in this magic, for it is your belief that gives it strength, which can push you on. His scarred

hand reaching into his pouch with cautious solemnity, the Doctor drew forth a magic powder made by the rites of old and anointed

all who gathered. Feel its power, feel your own, let the dust of the gods rain down. Become invulnerable to the attack you

will surely provoke, children of Africa. Let it cover your clothes as you pray to gods forbidden by name in this heathen land.

Consider yourselves prepared for what would follow.

Once I was talking to this G.E.D. class in the Bronx, talking about gentrification and urban renewal and class migration,

and this kid asked me, "If you was sent back in time, and was a slave, would you kill yourself?" It had absolutely nothing

to do with the topic at hand and its odd posing hinted at why this dude was getting his G.E.D. in the first place, but I

tried to answer him. "No, I probably would not," I told him, citing my family responsibilities as reason: I got kids, a wife,

parents. Apparently, this was the wrong answer. He would throw himself off a building, he insisted. I tried to tell him the

buildings weren't that tall back then, only two stories, so he'd probably only break his leg, but this knucklehead wasn't

trying to listen.

In the darkness, the Africans gathered behind the home of Peter Vantilborough; two of the men who were enslaved by Vantilborough

were eager members of the party. As the duo approached the outhouse in order to set it ablaze, the others hid behind the trees

and waited, listened to their own nervous panting as they prepared to kill every pink-skinned rescuer who came running. "Light

the fire!" came nervous, fast whispers as the Africans crouched around them, feeling most alive in the moment that life was

most at risk. Make the deed done, seal the fate tonight. In the back of the yard by the outhouse, kindling in hand, Vantilborough's

slaves accomplished their ignition. Sparked the fuse that would change the lives of all who waited eagerly in the shadows

beyond.

A will for havoc united the Africans, regardless of ethnicity or birth land. A determination to end the atrocity of their

bondage. Soon moonlight was eclipsed as flames copulated around them, flames reveling in greed and consumption, the fire's

flicker giving the illusion of motion to the frozen Africans nestled in hiding places all around, muskets, machetes, and swords

in hand.

New York was a city of solid brick houses, but the houses were covered by wooden roofs, and usually wooden storehouses and

stables stood right behind them, all packed tightly together like matches in a box. Fire and fear were synonymous. It was

great poetry that the key to the community's destruction could be obtained by even its most downtrodden, penniless citizen.

In fire was equality. Few men had the ability to build something in this world, but all had the power to destroy in it. Properly

placed, one smoldering coal could reduce a rich man to a pauper, turn a controlled community into a chaotic one. When a fire

started, only the hurried summoning of the four-year-old fire brigade and the quick formation of a bucket brigade—a line of

neighbors passing water from a well or river to the inferno—could offer defense from it. How it shined in the black balls

of the Africans' eyes, jumping red and orange that symbolized the return of freedom and all of its meaning which had been

denied. Revenge and rage crackled before them, the fire's heat their own, its will for destruction just a sample of what beat

in their breasts this night.

The Caucasians came running, you could see their pale, fishlike skin glowing in the night, sense the confusion in their rushed

gaits as they jogged forth, still gathering their clothes around them. Wait till they get closer, wait till they get closer,

then pull the trigger.

For the first wave of arrivals, their clothes did little to protect them as musket balls ripped through their European garments

before they had any understanding of what they'd run into. Five pink men lay dead at the rebels' feet in a dozen seconds,

six more ran wounded from the offering. If the gunpowder didn't warn the rest of the city, the wounded would, and the rebels

stuffed their muskets with all the speed they could manage, packing in the powder, dropping in the ball. Prepare to shoot,

pick them off as they come in.

The colonists quickly raised a militia. They had the numbers, ten to one. They had the arms as well. The Africans knew this

would happen. They kept packing their muskets, shooting. Four more pale lives were claimed by the rebels, cut down like ripe

cane. Every time another European life was extinguished, the Africans realized a moment of freedom. Rejoice in blood, if nothing

else is offered.

It was minutes before the two dozen Africans were overtaken, sent running toward whatever future was left for them. Years

of pining, months of planning and hoarding, and in a few minutes off the hour it was done. The Doctor's powder had reminded

them that they were brave, done little more, yet all that was expected of it. The lucky ones had already been slain for their

efforts, been given the release of warriors. For the rest, it was time to retreat from the immediate reality. On an island,

into a foreign land, in cold climate alien to them. Not running to anything—just running.

Shocked in the middle of the night, their own dark, guilt-ridden fears given form and force before them, the Caucasians thought

their Judgment Day was upon them. A hasty dispatch was sent to the British troops at the garrison, miles below at the southern

tip of Manhattan Island. But before the British soldiers could even arrive, the Africans had disappeared into darkness. Regrouping

possibly, ending the first wave in the larger war.

As colonists rushed through the night trying to unite against the opposition, fear and confusion reigned. Among the predominantly

English and Dutch colonists a call to arms went out, demanding an end to any infectious thoughts of mass African uprising.

The rebels kept running, the calls to arms echoing behind them. The sounds of the dogs barking their own excitement at the

growing hunt.

North, go north, just run. Away from the mob the whites have created to own your bodies once more. Run back into the darkness

as your own attempt at light is being doused behind you. Don't look back, there's nothing behind you anymore.

Not that there was far to go. Manhattan, the island, inescapably finite. They wouldn't make it far enough north that crossing

the narrows of the Harlem River into the mainland Bronx beyond would even become an issue. The militia, without need to hide

by day nor avoid the main trails, made it to the top of the island past Inwood before the Africans could ever hope to manage

to. Even if the Africans had broken through that tightly sealed barrier, further reinforcements from Long Island and Westchester

quickly swarmed in as second and third armies. The Africans were stuck in the woods, hiding. Many of them were new arrivals;

some had been on the island less than two years, the others only months and could not even speak English. Few would have even

seen snow before arrival and lacked any practical knowledge of how to survive in the harsh North American winter. The pain

of April is the summer heat is forgotten at sun's setting, the night is as cold as a day from three months before. Yet still,

stride and stumble, they moved. Callused feet numb and blistered, flesh scraped raw by the branches of the wild brush they

hid among. Too scared to stick to any path recognized, listening between the rhythm of their own footfalls to hear of other

beats of feet behind them.

Sometimes, when in Central Park, I can hear them coming, still. Close your eyes, think, and it's there. Like hell's still

behind them. Fleeing steadily, birds from a storm. Stand in the right place in Central Park and you can look up and only foliage

and bedrock will fill your vision and the specter of the lost Manhattan is revealed. The true New York, a place beyond skyscrapers

and concrete, out of time and beyond the industrial imagination. Then, you can almost see them there, past the tree line,

hiding. Standing as still as they can and praying to those failed gods to elude your focus. Wasting among the shrubbery. Waiting

for you to pass so they can breathe once more.

Stuck without shelter or food in New York's cold April nights, facing certain death regardless of course of action, the six

ex-slaves responsible for organizing the rebellion exerted a final act of defiance, one last moment of leadership. Weapons

turned against themselves, those six chose to take their own lives before the slavers could get the chance. Ending the pain

of starvation, fear, and exposure in an act of small victory.

The rest of the Africans were much less fortunate.

There was no quiet end to this engagement, even for those who admitted defeat. Near collapse, the surviving rebels turned

themselves in to the colonists, only to be thrown in with all the other slaves that had been rounded up in the mass hysteria

they'd help create. In response to a conspiracy of two dozen, seventy slaves were seized and thrown into jail by the panicking

pink skins. No brown New Yorker, regardless of innocence or alibi, was safe from a population of colonists who had seen their

dominance challenged, their sense of security revealed as illusion. It was madness, and even some of those in the moment could

see its true nature. Covering the event, the Boston News Letter compared the shrill reactionary insanity that now infected

the New York colony to the curious incident that had recently taken place in the northern colony of Massachusetts, in that

town of Salem. People were suspicious of everything. Damn, even the shadows, for they are black, too.

Courtly justice was quick; the village needed a reason to calm once more. Out of the twenty-seven black people brought to

trial, twenty-one were found guilty and sentenced to death. The six others owed their freedom to a lack of incriminating evidence

and the intervention of the colony's governor, whose physical distance from the city also provided him a sense of reason currently

scarce on the isle. Solemnly, New York slowly began returning to normal. As a true sign of peace, politics took dominance

once more. Serious rebellion cases before the court rapidly devolved into petty sabotage. During their trials, the Africans'

welfare was often decided not on personal guilt but on the political party affiliation of the man who enslaved them. African

lives, which for a moment, had been taken very seriously, were once again treated as utterly trivial, now that the element

of fear was again removed.

Those that were chosen to die did so openly, cruelly, creatively. A public burning was always a crowd-pleaser. The victim

was brought from the jail in chains, tied to a stake above a large pile of dry wood as the crowd jeered and threw rotten vegetables

or whatever else was close to hand. It was an occasion as joyous as morbid, a festive frenzy to base one's day around. A cheap

day on the town, perfect to bring your whole family. First came the smoke, the victim struggling to breathe a line of clear

air. Then the flames lifting up began to overwhelm them, heating their irons so that they were sauteed in their own chains.

As to dogs before dinner, the smell of cooked meat further enticed the crowd.