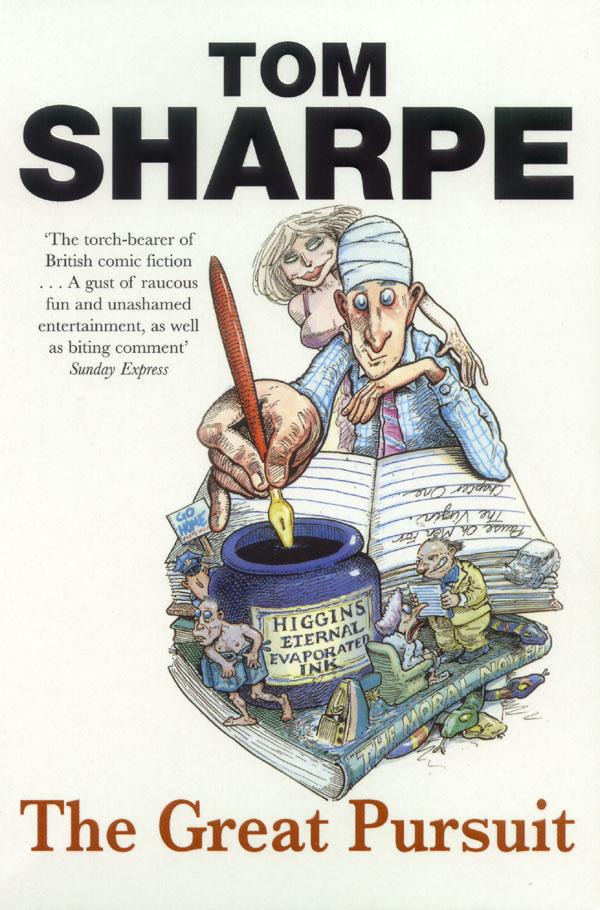

The Great Pursuit

by Tom Sharpe

Chapter 1

When anyone asked Frensic why he took snuff he replied that it was because by rights he should

have lived in the eighteenth century. It was, he said, the century best suited to his temperament

and way of life, the age of reason, of style, of improvement and expansion and those other

characteristics he so manifestly possessed. That he didn't, and happened to know that the

eighteenth century hadn't either, only heightened his pleasure at his own affectation and the

amazement of his audience and, by way of paradox, justified his claim to be spiritually at home

with Sterne, Swift, Smollett, Richardson, Fielding and other giants of the rudimentary novel

whose craft Frensic so much admired. Since he was a literary agent who despised nearly all the

novels he handled so successfully, Frensic's private eighteenth century was that of Grub Street

and Gin Lane and he paid homage to it by affecting an eccentricity and cynicism which earned him

a useful reputation and armoured him against the literary pretensions of unsaleable authors. In

short he bathed only occasionally, wore woollen vests throughout the summer, ate a great deal

more than was good for him, drank port before lunch and took snuff in large quantities so that

anyone wishing to deal with him had to prove their hardiness by running the gauntlet of these

deplorable habits. He also arrived early for work, read every manuscript that was submitted to

him, promptly returned those he couldn't sell and just as promptly sold the others and in general

conducted his business with surprising efficiency. Publishers took Frensic's opinions seriously.

When Frensic said a book would sell, it sold. He had a nose for a bestseller, an infallible

nose.

It was, he liked to think, something he had inherited from his father, a successful

wine-merchant whose own nose for a palatable claret at a popular price had paid for that

expensive education which, together with Frensic's more metaphysical nose, gave him the edge over

his competitors. Not that the connection between a good education and his success as a

connoisseur of commercially rewarding literature was direct. He had arrived at his talent

circuitously and if his admiration for the eighteenth century, while real, nevertheless concealed

an inversion, it was by exactly the same process that he had arrived at his success as a literary

agent.

At twenty-one he had come down from Cambridge with a second-class degree in English and the

ambition to write a great novel. After a year behind the counter of his father's wine shop in

Greenwich and at his desk in a room in Blackheath the 'great' had been abandoned. Three more

years as an advertising copywriter and the author of a rejected novel about life behind the

counter of a wine shop in Greenwich had completed the demolition of his literary ambitions. At

twenty-four Frensic hadn't needed his nose to tell him he would never be a novelist. The two

dozen literary agents who had refused to handle his work had said so already. On the other hand

his experience of them had revealed a profession entirely to his taste. Literary agents, it was

obvious, lived interesting, comfortable and thoroughly civilized lives. If they didn't write

novels, they met novelists, and Frensic was still idealistic enough to imagine that this was a

privilege; they spent their days reading books; they were their own masters, and if his own

experience was anything to go by they showed an encouraging lack of literary perspicacity. In

addition they seemed to spend a great deal of time eating and drinking and going to parties, and

Frensic, whose appearance tended to limit his sensual pleasures to putting things into himself

rather than into other people, was something of a gourmet. He had found his vocation.

At twenty-five he opened an office in King Street next to Covent Garden and sufficiently close

to Curtis Brown, the largest literary agency in London, to occasion some profitable postal

confusion, and advertised his services in the New Statesman, whose readers seemed more prone to

pursue those literary ambitions he had so recently relinquished. Having done that he sat down and

waited for the manuscripts to arrive. He had to wait a long time and he was beginning to wonder

just how long his father could be persuaded to pay the rent when the postman delivered two

parcels. The first contained a novel by Miss Celia Thwaite of The Old Pumping Station, Bishop's

Stortford and a letter explaining that Love's Lustre was Miss Thwaite's first book. Reading it

with increasing nausea, Frensic had no reason to doubt her word. The thing was a hodgepodge of

romantic drivel and historical inaccuracy and dealt at length with the unconsummated love of a

young squire for the wife of an absent-bodied crusader whose obsession with his wife's chastity

seemed to reflect an almost pathological fetishism on the part of Miss Thwaite herself. Frensic

wrote a polite note explaining that Love's Lustre was not a commercial proposition and posted the

manuscript back to Bishop's Stortford.

The contents of the second package seemed at first sight to be more promising. Again it was a

first novel, this time called Search for a Lost Childhood by a Mr P. Piper who gave as his

address the Seaview Boarding House, Folkstone. Frensic read the novel and found it perceptive and

deeply moving. Mr Piper's childhood had not been a happy one but he wrote discerningly about his

unsympathetic parents and his own troubled adolescence in East Finchley. Frensic promptly sent

the book to Jonathan Cape and informed Mr Piper that he foresaw an immediate sale followed by

critical acclaim. He was wrong. Cape rejected the book. Bodley Head rejected it. Collins rejected

it. Every publisher in London rejected it with comments that ranged from the polite to the

derisory. Frensic conveyed their opinions in diluted form to Piper and entered into a

correspondence with him about ways of improving it to meet the publishers' requirements.

He was just recovering from this blow to his acumen when he received another. A paragraph in

The Bookseller announced that Miss Celia Thwaite's first novel, Love's Lustre, had been sold to

Collins for fifty thousand pounds, to an American publisher for a quarter of a million dollars,

and that she stood a good chance of winning The Georgette Heyer Memorial Prize for Romantic

Fiction. Frensic read the paragraph incredulously and underwent a literary conversion. If

publishers were prepared to pay such enormous sums for a book which Frensic's educated taste had

told him was romantic trash, then everything he had learnt from F. R. Leavis and more directly

from his own supervisor at Oxford, Dr Sydney Louth, about the modern novel was entirely false in

the world of commercial publishing; worse still it constituted a deadly threat to his own career

as a literary agent. From that moment of revelation Frensic's outlook changed. He did not discard

his educated standards. He stood them on their head. Any novel that so much as approximated to

the criteria laid down by Leavis in The Great Tradition and more vehemently by Miss Sydney Louth

in her work, The Moral Novel, he rejected out of hand as totally unsuitable for publication while

those books they would have dismissed as beneath contempt he pushed for all he was worth. By

virtue of this remarkable reversal Frensic prospered. By the time he was thirty he had

established an enviable reputation among publishers as an agent who recommended only those books

that would sell. A novel from Frensic could be relied upon to need no alterations and little

editing. It would be exactly eighty thousand words long or, in the case of historical romance

where the readers were more voracious, one hundred and fifty thousand. It would start with a

bang, continue with more bangs and end happily with an even bigger bang. In short, it would

contain all those ingredients that public taste most appreciated.

But if the novels Frensic submitted to publishers needed few changes, those that arrived on

his desk from aspiring authors seldom passed his scrutiny without fundamental alteration. Having

discovered the ingredients of popular success in Love's Lustre, Frensic applied them to every

book he handled so that they emerged from the process of rewriting like literary plum puddings or

blended wines and incorporated sex, violence, thrills, romance and mystery, with the occasional

dollop of significance to give them cultural respectability. Frensic was very keen on cultural

respectability. It ensured reviews in the better papers and gave readers the illusion that they

were participating in a pilgrimage to a shrine of meaning. What the meaning was remained,

necessarily, unclear. It came under the general heading of meaningfulness but without it a

section of the public who despised mere escapism would have been lost to Frensic's authors. He

therefore always insisted on significance, and while on the whole he lumped it with insight and

sensibility as being in any large measure as lethal to a book's chances as a pint of strychnine

in a clear soup, in homeopathic doses it had a tonic effect on sales.

So did Sonia Futtle, whom Frensic chose as a partner to handle foreign publishers. She had

previously worked for a New York agency and being an American her contacts with US publishers

were invaluable. And the American market was extremely profitable. Sales were larger, the

percentage from authors' royalties greater, and the incentives offered by Book Clubs enormous.

Appropriately for one who was to expand their business in this direction, Sonia Futtle had

already expanded personally in most others and was of distinctly unmarriageable proportions. It

was this as much as anything that had persuaded Frensic to change the agency's name to Frensic

& Futtle and to link his impersonal fortune with hers. Besides, she was an enthusiast for

books which dealt with interpersonal relations and Frensic had developed an allergy to

interpersonal relationships. He concentrated on less demanding books, thrillers, detective

stories, sex when unromantic, historical novels when unsexual, campus novels, science fiction and

violence. Sonia Futtle handled romantic sex, historical romance, liberation books whether of

women or negroes, adolescent traumas, interpersonal relationships and animals. She was

particularly good with animals; and Frensic, who had once almost lost a finger to the heroine of

Otters to Tea, was happy to leave this side of the business to her. Given the chance he would

have relinquished Piper too. But Piper stuck to Frensic as the only agent ever to have offered

him the slightest encouragement and Frensic, whose success was in inverse proportion to Piper's

failure, reconciled himself to the knowledge that he could never abandon Piper and that Piper

would never abandon his confounded Search for a Lost Childhood.

Each year he arrived in London with a fresh version of his novel and Frensic took him out to

lunch and explained what was wrong with it while Piper argued that a great novel must deal with

real people in real situations and could never conform to Frensic's blatantly commercial formula.

And each year they would part amicably, Frensic to wonder at the man's incredible perseverance

and Piper to start work in a different boarding-house in a different seaside town on a different

search for the same lost childhood. And so year after year the novel was partially transformed

and the style altered to suit Piper's latest model. For this Frensic had no one to blame but

himself. Early in their acquaintance he had rashly recommended Miss Louth's essays in The Moral

Novel to Piper as something he ought to study and, while Frensic had come to regard her

appreciations of the great novelists of the past as pernicious to anyone trying to write a novel

today, Piper had adopted her standards as his own. Thanks to Miss Louth he had produced a

Lawrence version of Search for a Lost Childhood, then a Henry James; James had been superseded by

Conrad, then by George Eliot; there had been a Dickens version and even a Thomas Wolfe; and one

awful summer a Faulkner. But through them all there stalked the figure of Piper's father, his

miserable mother and the self-consciously pubescent Piper himself. Derivation followed derivation

but the insights remained implacably trite and the action non-existent. Frensic despaired but

remained loyal. To Sonia Futtle his attitude was incomprehensible.

'What do you do it for?' she asked. 'Life's never going to make it and those lunches cost a

fortune.'

'He is my memento mori,' said Frensic cryptically, conscious that the death Piper served to

remind him of was his own, the aspiring young novelist he himself had once been and on the

betrayal of whose literary ideals the success of Frensic & Futtle depended.

But if Piper occupied one day in his year, a day of atonement, for the rest Frensic pursued

his career more profitably. Blessed with an excellent appetite, an impervious liver and an

inexpensive source of fine wines from his father's cellars, he was able to entertain lavishly. In

the world of publishing this was an immense advantage. While other agents wobbled home from those

dinners over which books are conceived, publicized or bought, Frensic went portly on eating,

drinking and advocating his novels ad nauseam and boasting of his 'finds'. Among the latter was

James Jamesforth, a writer whose novels were of such unmitigated success that he was compelled

for tax purposes to wander the world like some alcoholic fugitive from fame.