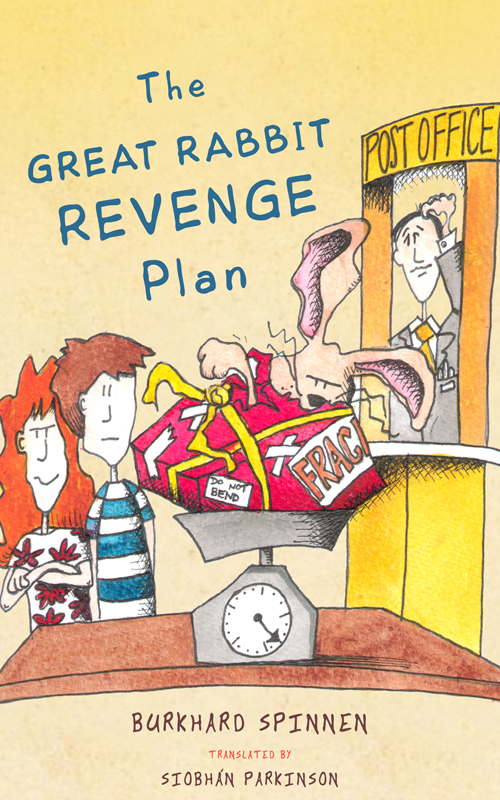

The Great Rabbit Revenge Plan

Read The Great Rabbit Revenge Plan Online

Authors: Burkhard Spinnen

The Great Rabbit Revenge Plan

About the author

Burkhard Spinnen was born in Germany in 1956 and lives as a writer in the German city of Münster. He has received many awards for his work, among them the Oldenburg Award for Young Adult Literature and the German Audio Book Award (for

Belgische Riesen

, the German version of

The Great Rabbit Revenge Plan

).

The Great Rabbit Revenge Plan

Burkhard Spinnen

Translated by

Siobhán Parkinson

First published 2010

by Little Island

an imprint of New Island

2 Brookside

Dundrum Road

Dublin 14

First published in Frankfurt am Main, Germany in 2000 by Schöffling & Co. Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH.

Copyright © Burkhard Spinnen 2000

Translation copyright © Siobhán Parkinson 2010

The author has asserted his moral rights.

ISBN 978-1-84840-945-3

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover illustration © Annie West 2009

Printed in Ireland by Colourbooks

Little Island received financial assistance from

The Arts Council (An Chomhairle EalaÃon), Dublin, Ireland.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Konrad Makes an Entrance

The door opens.

âBy the way,' says Konrad, âit's totally bright outside.'

It's pretty bright now in the bedroom too, because light is coming in from the landing, and that's how Konrad can see one of the two occupants of the bed swiftly pulling the duvet up over his head. This person says something not very nice, something Konrad would never be allowed to say.

This person is

Dad

. Outside the house, he's called Herr Bantelmann. Inside, of course, Dad. And only very rarely, Wolfgang.

This person was not always Dad. He makes a big deal of this, and he's always making sure Konrad knows all about it. For thirty-one years, Dad was, among other things, a son and a constructor of model aeroplanes. He was the holder of a driving licence. He was the wearer of a beard. And later he was also the

young man

of the other occupant of the big bed.

He's only been Dad for ten years; and although ten years is rather a long time, Dad hasn't quite got used to Dadhood yet. He is least accustomed to Dadhood on Sunday mornings at eight minutes past six. And that's exactly what he says now. What he is saying is perfectly clear, even though he has the duvet over his head. Presumably Dad can see that it is eight minutes past six through a tiny breathing crack that he

has left between the mattress and the duvet. It says eight minutes past six in glowing red numbers on the digital alarm clock.

âKonrad,' says Dad's voice from under the duvet, âwhat have I forbidden you to do?'

Konrad thinks. Forbidden ⦠forbidden? Dad has forbidden pretty well

everything

. How could you possibly know which bit of everything he means at this particular moment?

Luckily, Konrad gets a bit of help. It comes from the person who is lying next to Dad in the bed and who was once his

young lady

. This person is

Mum

. Outside the house, Frau Bantelmann. Inside, of course, Mum; occasionally, Edith.

âIt has to do with coming into the bedroom,' she says.

Oh, yes, of course! Konrad gets it immediately. How could he have forgotten? There is a particularly serious rule that has to do with coming into the bedroom on Sunday mornings. You are supposed to, that is to say you should â careful, now, mustn't get this wrong! â on Sunday mornings you should not come in before ⦠a particular time. Unfortunately, what this time is escapes Konrad. That is stupid. And so that he won't get it wrong, just to be on the safe side, he says nothing.

Luckily, Mum comes to the rescue again. âWhat time is it now?' she says, in a reproachful tone.

Konrad twigs. It looks like he's come in too early, and the time shown on the digital alarm-clock could be a clue as to what time not to come in at. Konrad looks at the clock.

âNine minutes past six,' he says. At least that much is not wrong.

âTerrific,' says Dad from under the duvet. He makes it sound like a very bad word. âAnd what have we forbidden you to do?'

All of a sudden, Konrad remembers. âI'm not supposed to come in before eight o'clock on Sundays. Except in an emergency â serious illness or fire.' Hey, he'd got it!

âBy the way â ' said Konrad.

But Dad roars: âAnd what else are you not supposed to do?'

Something comes back to Konrad. You are not, if at all possible, supposed to come into the parental bedroom before eight o'clock on a Sunday morning, and when you do come in, you must absolutely not, never under any circumstances, begin your first sentence with âby the way'.

Dad has explained it. In fact, he has often explained it. As recently, indeed, as last Sunday. It was round about this time, and Konrad had just come in. The expression âby the way', Dad had said, is something you use to bring a new subject into a conversation and hook it up to an old subject. He had even demonstrated it, the hooking up, with both hands. Konrad had understood. By the way is a linking expression. It's like this piece of string that you get and you tie two subjects together with it so that they don't fall apart.

âThat's right,' Dad had said. And so it follows, as night follows day, that a conversation cannot begin with âby the way'. For a âby the way' you need at least two subjects. Two! And on a Sunday morning at however many minutes past six, there is not yet even one subject. In fact there is absolutely no subject whatsoever.

At this point in the explanation, Dad had raised his voice, even though it was so early in the morning. âNo subject!' he'd said. There is no subject, because he, Dad, is not in the middle of a conversation but in the middle of a sleep. And if one of the two future conversationalists is still asleep, then the other conversationalist should bloody well watch out and under no circumstances come barging into the bedroom with a big, thick, fat, ugly âby the way'.

They'd practised it, last Sunday, the eight o'clock entrance and the beginning of a conversation. Until they'd got it right. Uh-oh. Konrad knows what's coming now. And he is quite correct. âGet out, and come back in,' says Dad from under the duvet.

âDoes he have to?' says Mum. Mum is soft-hearted. She keeps showing it.

âOkay,' says Dad from under the duvet, âyou're the soft-hearted one. Agreed. But who complains most if they can't get a lie-in? You or me?'

Now, this is what Dad always calls a ârhetorical question'. Rhetorical questions are questions that you don't have to answer, because the answer is already known. And because Mum really does get very cross, in spite of her soft-heartedness, when she can't get a lie-in, she doesn't have to answer now. Konrad considers rhetorical questions very useful. Unfortunately, his parents think up far more of them than he can. And unfortunately, Mum makes a sign to him now, which means âleave the room and come back in'.

Out on the landing, Konrad paces up and down for a while, so that Mum and Dad have enough time to fall asleep

again. They have to be asleep when he comes back in, otherwise it's just not right. On his fourth time up and down, he looks into his younger brother Peter's room and sees that he has kicked his quilt off and is now sleeping on all fours. Konrad takes a closer look. What is he like! His bottom in the air and his head on his forepaws like a sleeping dog. Recently, Mum and Dad were standing by Peter's bed and he'd been sleeping just like this, and Dad had said, âA natural wonder.' Peter has to hear that. It might amuse him.

âBy the way,' Konrad says, âDad said you are a natural wonder.' With this, he smacks Peter on his raised bottom.

âWha-at?'

âA natural wonder. You are a natural wonder.'

âUgh! What time is it?'

That's another one of those rhetorical questions. Peter is five years old and doesn't know the first thing about the time. He's just repeating what he hears people say. So there's no need to answer. And besides, Konrad has something better to be doing than reading the time for little brothers. He has to make a proper entrance. So, let's go for it!

The first thing he does is to open the bedroom door slowly and carefully, so that Mum and Dad don't get a fright. That's more or less what Dad said. And no sooner has he slipped through the door than he closes it again, so that no unnecessary light falls on Dad. He'd said it was possible that he was a vampire on Sunday mornings, and if vampires get too much light then they crumble into dust and that would be terrible because then Mum would have to brush an enormous pile of dust out of the bed. So now

Konrad is in the room. And it's completely dark. Mum and Dad have recently had new shutters installed and they close so tightly that not even the tiniest streak of light can get in. âHermetically sealed,' Dad said and he'd given a funny little laugh.

Konrad, however, is not feeling so very funny in this darkness. He takes a little step and immediately bangs his shin on the bed. It hurts, but at least now he knows where he is. What next? Oh, yes, he must feel his way around the bed until he reaches the crack between the two single mattresses. That's not so hard, and he finds the spot quite quickly. But then it gets more difficult. Because now he has to get into the bed and wriggle his way up the crack on all fours without banging Mum or Dad in a sensitive place with his knee or his elbow or knocking one of Mum's or Dad's teeth out or squashing their noses in with his desperately hard head. The best thing is to keep himself completely flat and to feel his way forward with his hands before wriggling any further. Dad has demonstrated this a few times, but Konrad had unfortunately laughed so hard that tears streamed from his eyes so that he couldn't see a thing.

Anyway, he seems to have reached a head. It's probably Dad's. It's easy to tell Mum's and Dad's heads apart. Mum's face is soft and she has long hair. Dad, on the other hand, has hardly any hair on his head but he is very scratchy in the face. Especially on Sunday mornings, because he doesn't shave on Saturdays.

Konrad gives another feel to be sure. No doubt about it, this is unquestionably Dad. So, he's made it. Now comes

the last part of the exercise. It's a bit embarrassing, though.

Konrad likes it very much when someone strokes his hair and whispers something nice into his ear, but to stroke someone else on the head and whisper something into their ear â that he finds rather embarrassing. Good thing it's so dark. Konrad strokes Dad's head and purrs like Aunt Thea's cat. It works. And now to say something nice. Konrad puts his mouth very close to Dad's ear.

Phe-ew! Dad stinks of garlic. Child poison! Mum and Dad were in a restaurant yesterday, and in the restaurants where Mum and Dad go without Konrad and Peter, there's nothing but child poison. The whole menu from beginning to end is child poison with double garlic. Konrad thinks this is terrible. âBy the way,' he says. âYou smell of garlic again.'

âKonrad!' says Mum, and Dad makes a scrunching sound.

Then the door opens and all of a sudden it is bright in the room again.

âBy the way,' says Peter. âI can't help being awake. There!' he points at the bed, where Konrad is by now half sitting on Dad's head. âKonrad! He woke me up.'

âGreat,' says Mum, getting out of bed. âI'm going to have a shower.'

Dad says something too, but you can't hear what it is, because Konrad has just belted Dad in the face with his knee and Dad is now holding his nose with both hands.

âWill you tell us a story?' asks Peter. He's scrambling into the bed now too, and as he tries to climb over Konrad he

gets him in the eye with an elbow. Konrad yells, but only a bit. Then he says, âYeah, will you tell us a story?'

And all three, Dad, Konrad and Peter, know that this is indubitably a rhetorical question.