The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March (51 page)

Read The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #Biography, #England, #Historical

Contemporary images of Isabella are rare. This worn face is one of the few which certainly represent her. It appears on the same tomb in Winchelsea Church as the face of Edward II reproduced on the opposite page.

This carving in Beverley Minster is thought to represent Isabella. Conclusive evidence is lacking, but it resembles several queen’s heads of the early fourteenth century which are probably stylised representations of Isabella or Philippa of Hainault.

Nottingham Castle as it might have appeared in the sixteenth century. Although the tunnel which Sir William Montagu used to gain access to the castle and capture Roger survives, the castle itself was almost entirely demolished in the seventeenth century.

Trim Castle – the largest castle in Ireland – was Roger’s seat in that country. Like Wigmore, it was rarely used as a residence after Roger’s death, and the ruins are largely those of buildings Roger would have known.

The solar of Ludlow Castle built by Roger in readiness for the visit of Isabella and the young king on 2 June 1328. It is situated at the opposite end of the great hall from the old solar, where Roger’s wife, Joan, probably stayed.

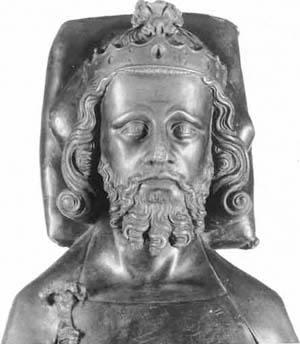

Edward II: face from the effigy on his tomb in Gloucester Cathedral.

Edward II: face from the tomb of a member of the Alard family in Winchelsea Church.

Roger and Isabella with their army at Hereford (and Hugh Despenser being executed in the background). This illumination, from a copy of Froissart’s chronicle, dates from the 1460s – more than 130 years after the event – but it shows how late medieval readers pictured the couple in the course of their invasion.

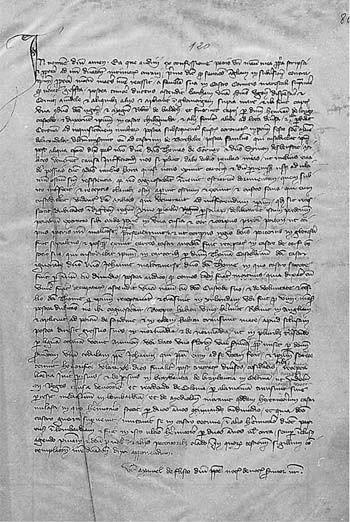

The Fieschi Letter [AD Hérault, G 1123]: ‘one of the most remarkable documents in the whole of English medieval history’ (G.P. Cuttino). See

Chapter Twelve Revisited

.

NOTES

Introduction

1.

Dramatic works which have dealt with Roger Mortimer include: Christopher Marlowe,

Edward II

(1594) and J. Bancroft,

The Fall of Mortimer

(1691), late editions being attributed to William Mountfort. The verse satire is Francis Richardson,

An Ode to the Pretender … to which is added Earl Mortimer’s fall

(1713). Mortimer’s usefulness as an object of satire in the eighteenth century is evident in two works,

The Lives of Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, and of Robert, Earl of Oxford &c …

(1711) and

The Norfolk Sting, or the history and fall of Evil Ministers

(1732). Alma Harris,

In Days of Yore: Queen Isabella and Sir Roger Mortimer: A Royal Romance

(Nottingham, 1995) is the only recent non-academic part-biography of Roger Mortimer. An earlier part-biography was J. Adamson,

The reigns of King Edward II

,

and so far of King Edward III

,

as relates to the lives and actions of Piers Gaveston, Hugh de Spencer, and Roger, Lord Mortimer

(1732). A fictional account of Roger Mortimer (apart from those primarily concerning Isabella) is Emily Sarah Holt,

The Lord of the Marches: or the story of Roger Mortimer: a tale of the fourteenth century

(1884).

2.

The sole doctoral thesis concerning Roger Mortimer has only recently been completed by Paul Dryburgh at the University of Bristol. The text of this book was completed while Dr Dryburgh’s thesis was still unsubmitted, and the author has not had access to any part of Dr Dryburgh’s written work.

1: Inheritance

1.

25 April 1287 is the most probable date of Roger’s birth. The ages given for him in the various

Inquisitions Post Mortem

relating to his father’s death (1304) suggest two dates. The first of these is derived from the statement that he was seventeen on the feast of St Mark last, i.e. born on 25 April 1287. The other is that he was seventeen on the last Feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross, i.e. 3 May 1287. The date of the Feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross was the date of the demise of the estates of Edmund Mortimer (Roger’s father) to Geoffrey de Geneville in 1300, and this has probably been confused with his birth. A family chronicle, written almost a century later, states he was sixteen and a quarter at the time of his father’s death, which would imply a birthdate about April 1288, and the

Complete Peerage

indeed notes that the Chronicle of Hailes (British Library, Cottonian MSS, Cleopatra D3) states he was born on 17 April 1288. Also the Wigmore Annals in the John Rylands Library (transcribed in B.P. Evans’s Ph.D. study of the family, for details of which see Bibliography) mentions Roger was born ‘circa festum apostolorum Philippi et Jacobi’ in the year 1288 (1 May). This chronicle is a year out on a number of details, however; with regard to the birth of Edmund FitzAlan it

is two years adrift, a reflection on its being written a long time after the event. Also with regard to the fifteenth-century family chronicle, which has clearly been compiled from earlier sources (including, quite possibly, the Wigmore Annals in the John Rylands Library), although this correctly dates Edmund’s death in one paragraph, in the paragraph in which it states Roger was sixteen and a quarter at the time it places the death a year early, in the thirty-first year of the reign of Edward I: i.e. November 1302–3. The

Inquisitions Post Mortem

are the nearest to a contemporary source we have, all being written in the summer of 1304; none of these mentions 1288 as the date of his birth, and most favour the St Mark date. The date of 25 April 1287 was probably supplied centrally by a clerk of the family within a few weeks of the death of Edmund Mortimer, and this, being legally binding, and the only date of birth definitely associated with him in his lifetime, must therefore be considered the most trustworthy evidence we have. Confirmation of the day, 25 April, is perhaps to be found in the number of grants that Roger awarded himself and his son Geoffrey on that day in 1330 (see

Cal. Charter Rolls

, pp. 172, 175).

2.

Each head of the family had named his first-born son after his father since the mid-twelfth century. See

Complete Peerage

, ix, pp. 266–85. This custom seems to have held true for the Mortimers from the mid-twelfth century to the fifteenth. It was also true for the inter-related family of Berkeley, for almost exactly the same period (until the death of the fifth lord in 1404).