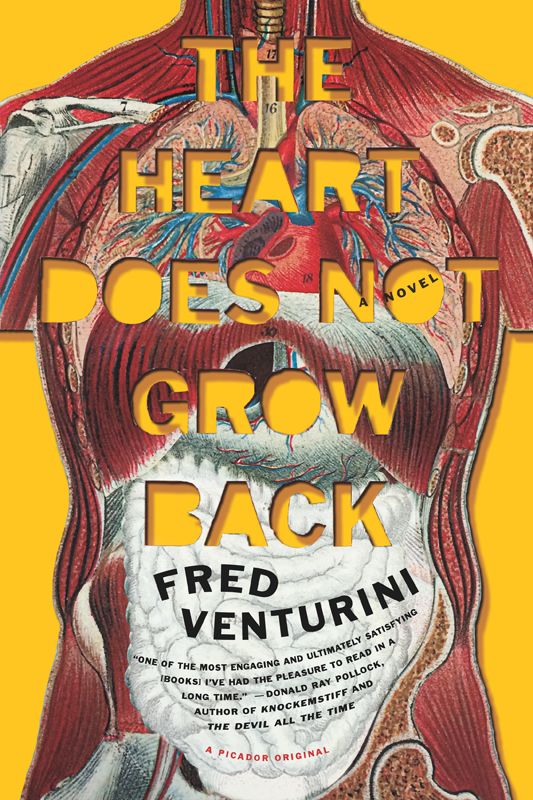

The Heart Does Not Grow Back: A Novel

Read The Heart Does Not Grow Back: A Novel Online

Authors: Fred Venturini

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

For Tom Pigg, 1982–2009

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Graduation was supposed to go like this:

Mack and me on the stage, waiting our turn to snag diplomas. The gym is packed and I look into the corners of the bleachers, into the drawn curtains of the stage we’re on, into the faces of the crowd, some of them staring back through the glass eyes of camcorders and cameras, and I remember all the little things that brought us here. I find my mother, who’s sitting in one of the reserved seats with Regina. Regina’s already graduated, playing volleyball for the local community college, waiting on me to graduate so that she can get into a four-year school near Boston, because I’m headed to Harvard. We’re in love, and experimenting with all the ways love can be expressed. I have a promise ring in my pocket—that awkward high school trinket that’s supposed to be the cheap precursor to an engagement ring. She already has my class ring, which I’ve never worn, purchased just for her, wrapped in yarn so that it will fit her finger, my mark upon her in pewter and emerald.

Mack’s dad is there. Sure, he slugged Mack a few times with those calloused lineman’s hands, scarring his knuckles on Mack’s orbital bones, but he’s at the graduation and for one night, they’ll hug and cry and Mack will go away to his division-one baseball program, already drafted by the Cincinnati Reds or some other Midwest team who caught wind of his skills and potential.

Principal Turnbull will announce Mack’s full scholarship to a place like Northwestern or Southern Illinois, something close to home but Division I all the way. He’ll announce that he’s a late-round draft pick, and his rights belong to a bona fide actual Major fucking League Baseball team.

The principal will announce my full scholarship to Harvard, where I will study law so that I can best negotiate Mack’s contracts when he really needs a big-time agent. Everyone who used to call me nerd or fuckwad now wishes they had a premium scholarship to a prestige school. They wish they had Regina Carpenter following them to Boston. They will cling to their moderate high school accomplishments in the classroom and in sports, and they’ll go to the community college for two years, which is just a glorified high school with ashtrays and a bigger parking lot, and then they’ll never finish and go crawling back to the family farm, or the family gravel business, or the family truck business.

That night, Mack and I will drink until we’re half-blind and fuck our hot girlfriends and people will congratulate us time and time again, and the compliments will never get old. The sun will come up and we’ll have to leave the women behind for our summer vacation, which we’ve been saving for. Why not spend our savings? We won’t have to spend a dime at college out of pocket, so we’ll rent that Ford Mustang convertible we talked about all the time and leave in the midafternoon, just after lunchtime, headed west for California, and the days and miles will uncurl before us, melting together until no day and no mile matters; there’s just possibility and the certainty we can bend moments until they’re congruent with our will. We’d imagined this. We’d talked about this, and wanted this and there it would be, better than we could have hoped for, just absolutely fucking perfect.

When you get to a moment you’ve waited so long for, sometimes you can’t enjoy it. Sometimes you realize you wasted so much valuable time waiting, wishing away hunks of your life, imagining the goals and moments and successes and dreams. After a while, life shifts from this big thing in front of you to this hazy, distant thing behind you, but in that moment, we wouldn’t care because the wait was worth it.

We’d waited through grade school to become junior high-schoolers. We’d waited to become freshmen. We’d waited to become seniors. We’d waited for our graduation, for college, for a life we had figured out. We’d waited not knowing that waiting was the same as dying.

Sometimes dreams come true. Other times, you end up counting backward from ten with a mask on your face, drifting away under anesthesia thinking,

I can’t believe I fell for this.

ONE

When I was in sixth grade I hated recess. I didn’t play sports, which left me alone, choosing to pass the time on a swing or just walking around with my head down and my hands jammed in my pockets. Not that I hated being alone—I actually preferred it, but during recess, everyone could see that you were alone and judged you accordingly.

I was swinging one day when they came to me with a blindfold. There were three of them—Lynn, Amy, and Kara—that cluster of grade-school girls that could never be broken apart, a clique tougher to split than atoms. They explained the rules of the blind-man game.

I can’t say I wasn’t paralyzed by tits and legs, hair and smiles. I could mention specifics, but really, it doesn’t matter what those parts looked like, only that they had them.

“Do you trust me, Dale?” one of them said. I don’t remember which one, but it doesn’t matter; they were one person back then, one voice meant to draw you into trouble, hypnotic as strippers and capable of the same broken promises.

Of course I didn’t trust them, but of course I couldn’t turn them down. They put the blindfold on me, touching my neck and face, their fingernails clicking as they tied the knot.

They led me through the playground with a scrap of T-shirt serving as the blindfold, the material so thin I could see everything through a milky-white screen. School was almost out and even in May, the Illinois heat felt strong enough to make stones burst. I soaked the blindfold with sweat fueled by heat and nerves.

We neared the metal post of the jungle gym. I knew they were going to lead me right into it, face-first. And I saw it coming, a metal pole I’d climbed dozens of times, making my hands smell like pennies for the rest of the school day.

Of course I knew that entertainment was the sole purpose of the blind-man game, so what was I supposed to do? Ruin their game and risk them never speaking to me again? I’d waited years for this encounter, and I wasn’t going to fuck it up. I took my medicine—hard. I made it more real than they expected, going forehead first, dazing myself, falling down on purpose so I could have their hands upon me again. They bent over, laughing, their hot breath on my face smelling like cafeteria sloppy joes and potato chips and heaven, their long hair dangling against my skin, a wilderness of girls surrounding me as I got to my feet.

With vision limited, my ears were greedy for sound—basketballs dribbling as tennis shoes clopped against blacktop, the skid of gravel and the occasional hollow thud of a kickball game, the voices of squealing kids melded together into a mess of noise, like a chorus of crickets screeching at night, or what God hears when he listens to all the prayers at once.

The swing-set post came next, and I took it on forehead-first. Then the chain-link fence. They tripped me over a teeter-totter with one of the saddles missing. I thought I was entertaining them, that we could do this forever, every recess, maybe even do it before senior graduation, or in the backyard of our house, where I would live with three wives who smiled every time I tripped over the coffee table or ran face-first into the patio door.

After pinballing around long enough, I sensed other kids following us around, enjoying the festivities. Having so many eyes on me gave me a sick comfort, like sitting down on a toilet seat that was delightfully warmed by someone else’s dirty ass. They kept leading me along and I loved having their attention, even if it was centered on my torture. Then, the screen of white began to reveal a moving shadow, not a pole. The dribble of a basketball became increasingly louder, along with the cries of sports jargon, such as “Screen!” or “Help!” and hands clapping, hoping to receive a pass. Other shadows joined. We were nearing the main basketball court, where the boys played serious, competitive pickup games during recess periods.

The girls were going to lead me into a squadron of distracted players to interrupt the game and see what would happen. Seeing a pole coming and embracing the blow is one thing, but this would have different consequences. I didn’t think having the attention of the elite boys of sixth grade in this fashion was good for my long-term health—but I especially feared Mack Tucker.

Mack “Truck” Tucker was the superstar basketball and baseball player. He had no noticeable intelligence that I could detect from my dark and silent corner of the classroom, but he was the epicenter of the sixth grade because his rugged looks belied his age and his athletic prowess was unmatched, allowing him to meet the two most important criteria in life—the girls fawned over him, and the guys wanted to be him. Guys would practice their asses off with the intention of dethroning him on the court or striking him out in playground games of stickball. These brave souls were perpetually left in his wake on his way to a smooth jumper, or with their hands on their hips, watching Mack trot around makeshift bases, winking at girls, the ball not landing until he was almost to second base. Girls were like a Greek chorus perpetuating his myth, scribbling about him on the cardboard backs of loose-leaf notebooks, enclosing his name in hearts and arrows, putting their own names under his with a plus sign in the middle.