Read The Heart of the Country Online

Authors: Fay Weldon

The Heart of the Country (21 page)

I told them about the wickedness of men, and the wretchedness of women. I told them they were being had, cheated, conned. That they were the poor and the helpless, and the robber barons were all around. They were being poisoned for profit: their children were being robbed of their birthright: the very rain that fell, the forests that grew, were being sold off, to be resold back to them. That they lived here in the heart of the country in the shadow of cruise missiles, in the breeze from Hinkley Point. That it was up to the women to fight back, because the men had lost their nerve. The crowd applauded my performance, though they missed the gist of the words. That was something. I pointed to the effigy of Angus on my right and Arthur to the left.

‘I blame the guilty men,’ I yelled. ‘Seducers, fornicators, robbers, cheats!’

How they cheered!

And this was the signal for my friend Ros to pick up the Georgian leather bucket, standing so innocently there beside Flora’s conch throne, but actually filled with petrol by me just before I began my speech. Ros flung the contents over Angus’ effigy. I flung a lighted match after it. I hadn’t realized quite what the impact of flame on petrol is. In a word, startling. The crowd yelled, in horror, surprise and, I fear, delight.

Fire’s wonderful. So pretty, don’t you think? Not final and grudging and finite, like an explosion, but always offering a tentative, if noisy, way out. If, if! cries the fire. If I don’t catch, shrieks fire. If you’ve got water, if you can block out my oxygen, find the blanket and locate the extinguisher, perhaps, just perhaps, I’ll let you off this time! I’ll go out. Any offers? Got any ifs for me? What? None? And then stronger and stronger comes the roar – no, no stopping me now, no putting me out; on your head be it. See, I’m unquenchable, I’m everywhere, everything, crackle, leap and bound and lo – all gone! Up in flames, into ashes, into dust, goodbye!

It took the housewives on the float a moment or so before they realized what had happened. Fire has that effect. You tend to stare at rapidly ascending tongues of flame, and admire their beauty, before realizing they can hurt, burn and destroy. They leapt from the float in what I see as the order of their desire for survival. Jean was off first (she would!) then Natalie, then Ros, then Sally, then Jane, then Pauline and then myself, Sonia. I would quite happily have died there.

And Flora?

Flora didn’t get off the float at all. She was mesmerized not by the flames but by her good fortune. What had happened was that Arthur had just handed her a cheque for two thousand pounds. He’d put her flower painting into a Sotheby’s sale and it had fetched two thousand two hundred. He’d taken for himself only 10 per cent and he need never have mentioned the sale at all. He’d done what he said he would. He had achieved a moral act, finally. It killed Flora.

People shouldn’t change their natures, just like that. It doesn’t do. Surprise is bad for people. It was sheer surprise which kept Flora sitting there gawping at the cheque. The light bulbs on the top of the float were cracking and popping in the heat. The crowd was now bending backwards and away out of danger. There were shouts and cries: Bernard was uncoupling the tractor. ‘Baghdad Nights’ was standing off: ‘Star Wars’ was being manoeuvred backwards.

Flora sat all in virgin white on the voluminous snowy throne and no one noticed her in time, just sitting there. I think it was her very stillness made her invisible, her very whiteness. Oh my virgin sacrifice! Allow me to descend into maudlin sentiment, just for once. She was all of us, what we once were, young, pretty, innocent and stunned by the wonder of the world, its capacity suddenly to offer good when all that is expected is bad. The giant effigy of Angus toppled back towards the centre of the float, and loomed over the throne, as some kind of root fixture burned through, and bent back still further, and cracked, and down it fell on top of the throne, on top of Flora, and Flora died. I think from the smoke. I hope from the smoke. Something horrible in the foam upholstery. I don’t think she

burned.

Okay. She burned. Consider it. A paragraph of silence while we do. Memorial space, dedicated to writhing, horrified, twisting Flora. My fault.

And to the others we all know, who died horribly before their time. Not my fault.

My fault? Ros threw the petrol, I threw the match. I could make Ros do anything I wanted, and I did. Only Ros and me knew what we were going to do. Our demonstration. Our visual fix, so the crowds would know the way the heart of the country was going, and do something about it. So it landed me here. Fine! Flora, the virgin sacrifice, so the world could cure itself of evil and renew itself? Better still! I hope it works. I didn’t mean Flora to die, or anyone to die, of course I didn’t. Fate took a hand. I take it as a good omen that it did. Bad for Flora, good for mankind, in which of course we include women, the lesser inside the greater.

My guilt, my madness if you like, has been the murder in my heart. I don’t deny it; how can I? Because of the misfortunes of my life I have been murderous, full of hate. The fire didn’t put those feelings out: on the contrary, it

inflamed them, at least for a while. Eddon Hill drugs, Dr Mempton’s patience, something, has worked. I feel quite denuded of hate, all of a sudden, as if Flora had stepped down, all virgin white, and graciously extended her lily white hands, that she never once got in the scrubbing bucket, no matter how Natalie Harris and Jane Wandle nagged, and forgiven me. Well, and why not! I was only trying to help.

Flora had a funeral to which everyone came. Ros got probation; I got put in here. Something happened to Arthur, who put on weight and aged ten years between the carnival and the funeral, and lost the knack of pulling women. Or so Ros told me. He tried Ros and she simply laughed. Perhaps his good deed did him no good: made his Dorian Gray picture in the attic grow younger so he had to grow older. Virtue is its own reward, don’t think it isn’t, and sometimes it’s a positive drawback. Anyway, with Arthur less randy Jane was happier. Only when she has him helpless in a wheelchair, after a stroke, will she be truly at ease. Sometimes I understand why it is that some men fear some women so: if women are virtuous, if they insist on being victims, then their misery controls to the grave.

Angus? Angus did not forgive Natalie. He was tired of her, anyway. He’d said she could have the flat free until November, just about getting the timing right. He did not renew the lease, but when he’d calmed down did not deny she’d brought richness and happiness into his life, at least for a while. Jean was rather pleasanter to him, now she was on HRT, or hormone replacement therapy. Her horribleness turned out to be menopausal. Or so he said. Various West Country rings dealing with illicitly imported agricultural chemicals, were uncovered by the police, and the penalties weren’t just fines but prison sentences, so Avon Farmers disappeared only just in time. Arthur started a Garden Centre there instead, where the flowers and shrubs flourished immoderately, and where not a butterfly ever alighted. Something had indeed got into the soil, for good or bad. One of his assistants had a baby born with a crooked leg but that could happen to anyone: there’s an epidemic, remember, of handicapped babies. And another died of cancer, but that was hardly statistically surprising, and in the meantime, how the pot plants in Eddon Gurney bloomed!

In the delicatessen the till pinged almost nonstop and profits grew, against all expectation. With the coming of Jax had come good fortune. The animal was obviously happier in a home where there were no children. Gerard took anti-depressants and lost his social conscience and thereafter sold luxury foods to the non-hungry with equanimity. Pauline took up weight training: an excellent substitute for sexual activity for those whose husbands grow elderly and uninterested too soon for their liking.

Val Bains’ back got permanently better at carnival time. He was in the crowds watching when float no. 62 caught fire. He ran forward to help Bernard unhitch the tractor, and in bending and forgetting released some trapped nerve or other in his spine. He took the job in Street at a firm using the new computer technology; it was exacting work if not well paid. He would drop Sally off at work, and collect her on the way home. She was pleased to have so visible and caring a husband.

Natalie? Well, here’s a turn-up for the books. Natalie stepped into Flora’s shoes, with Bernard in the caravan, up by the tip. He’s ten years younger than she is, but who cares? She had nowhere to go when Angus turned her out of the flat, and she’s always got on well with Bernard and at least didn’t have the children to worry about. Ros went up to see her, not long ago. Natalie said she was happier than she had ever been in all her life. She was properly alive at last, she said, though looking forward to the spring. Winters in a caravan can be trying. No, she didn’t want the children back. What could she offer them? Ros thought perhaps she was on drugs. It was so damp and muddy up by the tip, and Natalie looked so happy without any real reason that Ros could see. But perhaps it’s just sex, sex, sex; you know what Bernard is, forever quenching his moral and mental torment in fleshly pleasures. I hope it is. God knows what will happen to her next: what does happen to the one in three women with children whose marriages end in divorce?

You are right, it’s worrying about that which has driven me into the nuthouse, and right out the other side. I am, alas, sane again. I am, Dr Mempton says, fit to leave. Why is he being so nice to me? What? I can hardly believe him. How many sessions with the psychiatrist does an ordinary patient have? he asks. One a week? One a

fortnight?

He’s joking. That is a monstrously low figure. Yes, I do realize he’s been coming

every day

. It

did seem strange. I now see it’s bloody irresponsible, if what he’s saying is true.

Love? Me? Who could love me? I make him laugh, Bill Mempton says. When was making someone laugh a recipe for love? This is very, very embarrassing, and not what I had in mind at all. Look at me! Puffy face, puffy hands, twitching. That’s the drugs. I talk too much. I am full of hate and self-pity. He knows that, better than anyone. He’ll be saying next all I need is the love of a good man. My God, he’s said it! Do Them Upstairs go for this sort of thing – doctor-patient romances? I hardly think so! Or is it that they reckon anything is better than the Eddon Method? Those deaths must have shaken management no end!

Not for Sonia Flora’s triumphant puff of smoke, her exaltation: not for Sonia Natalie’s glorious debasement: no, for Sonia comes a proposal of marriage from a good man, who knows her every failing. She can’t accept, of course. Happy endings are not so easy. No. She must get on with changing the world, rescuing the country. There is no time left for frivolity.

Fay Weldon

Mid October 1986

We hope you enjoyed this book.

For an exclusive preview of your next wickedly witty Fay Weldon book, read on or click

here

.

Or for more information, click one of the links below:

An invitation from the publisher

Read on for a preview of

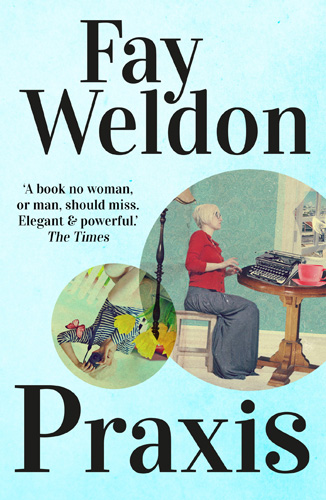

A portrait of a woman through time. Controversial, disturbing and witty—Fay Weldon’s most ambitious novel.

Praxis Duveen is a truly modern heroine, buffeted and battered by life, by women and by men, by herself – wry, funny, pretty innocent, knowing – yet surviving. Her story begins in the 1920s in the seaside town of Brighton. When we leave her in the in 1970s, in London, she has become – despite herself – a world-famous women’s leader.

I do not wet the bed now; at least not that: though soon, I dare say, the time will come when I do. I dread the day. I do not want to be an old woman sitting in a chair, wearing nappies, nursed by the salt of the earth. It seems unjust; not what Lucy and Benjamin meant at all; rolling about in their unwed bed, year after year, moved by a force which clearly had nothing to do with commonsense or anyone’s quest for happiness: until, their mission apparently accomplished, they rolled apart and went their separate ways, assisted by Butt and Sons, Solicitors.

I do not want to be an incontinent old lady. I would rather die. I feel today, my elbow throbbing and my toe swelling, that the time for dying will be quite soon. On Thursdays I go down to the Social Security offices, stand in a queue, and draw the money which keeps me for a further week. It should be possible for a postal draft to be sent weekly and myself to cash it at the local post office, but I do not like to make the request. I am an ex-con, and habit dies hard of not causing trouble to, let alone demanding one’s rights of, those in authority.

Those in authority, at any rate, in that strange grey world of bars and keys which I have inhabited, where cause and effect works in an immediate way, and the stupid are in charge of the intelligent, and each wrong-doer carries on his poor bowed shoulders the weight of a hundred of the worthy – from prison visitors to the Home Secretary – whose living is made, indirectly, out of crime, or sin, or financial failing, or criminal negligence: or, as with me, the madness of believing that I was right, and society wrong. Who did I think I was? I, Praxis Duveen.