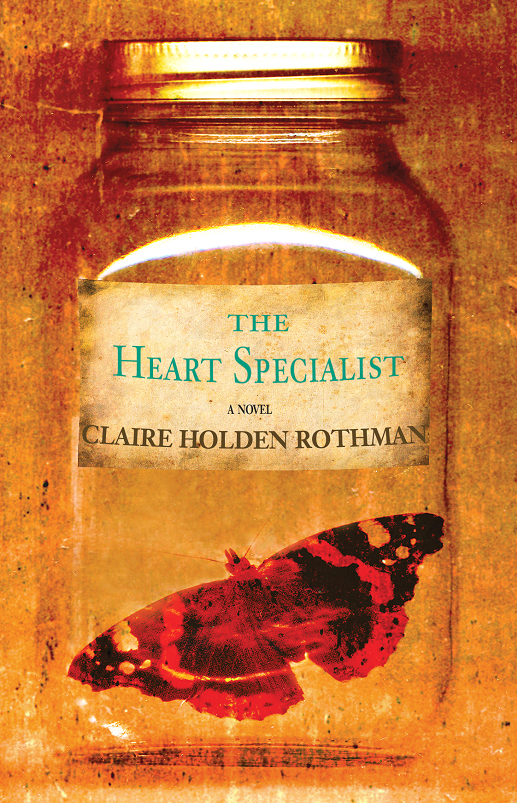

The Heart Specialist

Read The Heart Specialist Online

Authors: Claire Holden Rothman

Copyright © 2009, 2011 by Claire Holden Rothman

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

First published in Canada by Cormorant Books Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rothman, Claire, 1958–

The heart specialist / Claire Holden Rothman.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-56947-945-2

eISBN 978-1-56947-946-9

1. Women physicians—Fiction. 2. Self-realization in women—Fiction.

3.Montrial (Quibec)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR9199.3.R619H43 2011

813’.54—dc22

2011007814

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Arthur Holden

Cardiac anomalies may be divided, according to etiology,

into two main groups: those due to arrest of growth at

an early stage, before the different parts of the heart have

been entirely formed, and those produced in the

more fully developed heart by fetal disease.

— MAUDE ABBOTT, “CONGENITAL CARDIAC DISEASE,”

IN WILLIAM OSLER’S

SYSTEM OF MEDICINE

Still the heart doth need a language,

Still doth the old instinct bring back the old names.

— FRIEDRICH SCHILLER,

PICCOLOMINI

PRELUDE

THE SMALL WATCHER

Observe, record, tabulate, communicate.

— WILLIAM OSLER

My first memory of my father is of his face floating above me and weeping. The image dates back to 1874 during a particularly brutal winter in St. Andrews East, a town near the mouth of the Ottawa River in Quebec, about fifty miles from Montreal. The month was January. I would soon turn five.

What mechanism triggers memory, selecting images to press into the soft skin of a child’s mind? Often it is trauma, although at that particular moment the word had not yet entered my lexicon. I had no idea why my father had come into my room or why he was weeping. All I knew when I opened my eyes was that something was wrong. Routines had been disrupted, rules broken. My safe, small world had come unhinged.

My father smelled of pipe tobacco, a delicious smell that made me think of chocolate. I stared at the moustache drooping from his upper lip. I could have buried my face in that moustache, but of course I did no such thing. He was an imposing man whose moods were occasionally unpredictable. I just lay still and stared.

Not long after he left us, when the fields and roads were still glistening with ice, I came across one of his pipes abandoned in the barn in back of the house. I didn’t even pause to think. I picked it up and stuck it in my mouth. It was an experiment, an attempt to copy what I had seen him do hundreds of times, an attempt to bring him back. The result was a shock. It tasted awful, nothing like the sweet dark-chocolate smell of my memory. I spat until my tongue hurt and I had no saliva left.

That night, staring up at him from my bed, I was at a loss. I was only beginning to understand that there were people other than myself in the world, living lives separate from mine. To think that my father might cry confused me, so I shut my eyes, shutting out everything but his smell and the sounds of his quick and shallow breaths.

He spoke to me in French, which he did sometimes when it was just the two of us. I have no recollection of what was said. It was not about the trial or his dead sister, that much is certain. He never spoke of these things to anyone in the house in St. Andrews East. He probably tried to reassure me. I suspect I knew even then that he was lying. I could sense that things were very wrong, and suddenly, just like my father, I too began to cry. I must have gone on for some time because when I looked up he was gone.

He took only his clothes that night and the money he had scraped together for the baptism — Laure’s baptism, although at the time he would not have known it was to be Laure. He had chosen her name, just as he had chosen mine — Agnès — picking it out with my mother months before the births. Paul if a boy, Laure if a girl, names that worked in both French and English. In the end, Laure had to wait several years for her baptism. Grandmother took care of it, as she took care of so much else.

For the longest time I felt that I had chased my father away. My tears had sent him running. His face had been there one moment and then, after I shut my eyes and wept, he was gone. A child’s logic, I suppose, but logic nonetheless. What if I had kept still, I later could not help thinking. What if I had reached out my childish arms to embrace him? From that day on I lived with one thought paramount in my mind. I would find my dark, sad father and win him back. Though I could not claim to have known him well, and my first memory of him was almost my last, it did not matter. His face stayed with me through the years, as clear as on that night in January when he went away.

Contents

Saint Agnes’ Eve — Ah, bitter chill it was!

—

JOHN KEATS

JANUARY 1882, ST. ANDREWS EAST, QUEBEC

All morning I had been waiting for death, even though when it finally came the change was so incremental I nearly missed it. I had laid the squirrel out on a crate and covered it with a rag to keep it from freezing. Blood no longer flowed from the wound on its head, although it still looked red and angry. A dog or some other animal must have clamped its jaws around the skull, but somehow it had managed to escape, dragging itself through the snow to Grandmother’s property, where I had discovered it that morning near the barn door. It had been breathing then, the body still trembling and warm.

Now the breathing was stopped and its eyes were filmy. I blew on my fingers, which had numbed with cold, and went to my instruments bag. It was not leather like the one used by Archie Osborne, the doctor for St. Andrews East. It was burlap and had once held potatoes. Along with most of its contents, it had been pilfered from Grandmother’s kitchen. I took out a paring knife, a whetting stone and a box of pins in a tin that used to hold throat lozenges dusted with sugar. The blade of my knife was razor-thin and nicked in several spots. It didn’t look like much, but it was as good as any scalpel. I rubbed the whetting stone along the blade a few times then cracked the ice in the bucket with my heel and dipped in the knife to clean off the sugar dust.

My dead house left a lot to be desired. It was too cold in January for stays of decent duration. After two winters of working here, however, I was accustomed to it. I had organized it well, with microscope in the far corner hidden beneath a tarpaulin and twenty-one of Grandmother’s Mason jars lined up on the floor against one wall, concealed by straw. Above the jars, on a shelf fashioned out of a board, was my special collection, which consisted of three dead ladybugs, the husk of a cicada beetle, the desiccated jaw of a cow and my prize: a pair of butterflies mounted with thread and glass rods in the only true laboratory bottle I’d been able to salvage from my father’s possessions two years earlier, before Grandmother had them carted away to the junkyard. I took only three things for myself — my father’s microscope and slides, a textbook and that bottle. Any more and my grandmother would surely have noticed.

To a person glancing through the door, my dissection room appeared to be ordinary barn storage. Grandmother had forbidden me and Laure to play here, claiming the floorboards had rotted and we would fall through and break our legs. I had to use the back entrance for my visits, accessed by a path in the forest that abutted Grandmother’s land.

The squirrel’s yellow teeth poked through its lips. Its paws, curled to the chest as if it were begging, resisted my efforts to open them. The animal was already beginning to stiffen, but whether this was from cold or rigor mortis I could not tell. Its legs were also hard to manoeuvre, but somehow I managed to get the body done, laying him out on his back like a little man. My pins had a delicate confectionary smell that was incongruous with the odour of newly dead squirrel. I sniffed as I fastened him down, wincing as the metal pricks punctured his hide. The last preparatory step involved the microscope, which I lugged to the crate next to the dissection area for easy access.

My knife pierced the belly skin, releasing a gush of pink fluid that arced up, splattering the camel-hair coat Grandmother made for me last Christmas. I stepped back, staring stupidly at the line streaking my front, then reached for my apron. I had been careless. A fault I knew well, as Grandmother pointed it out to me every single day. She was right. I tended to forget about the most basic things: my hair was often half undone, my stockings sagged at my ankles.

Up until that day in the barn I had worked mostly with plants and insects. The closest I had come to anything alive were the tiny creatures inhabiting the scum of ponds or nestling in the bones of meat on the turn. This was the first time an animal with blood still warm in its veins had fallen into my hands. I cut again, this time down the middle, adding two perpendicular slits at the ends to form doors in the animal’s belly. These I peeled back and pinned, exposing the dark innards. My fingers were wet and red. Behind me there was a gasp.