The Hidden Oasis (10 page)

Authors: Paul Sussman

‘Thanks, Alex,’ he murmured, knowing that if it hadn’t been for the photo, he’d still be drinking now. ‘What would I do without you?’

He gazed out for a while longer, the coffee continuing the work of the cold shower, clearing and ordering his mind. He then returned the cup to the kitchen, dressed and padded along the corridor to his study at the far end of the apartment.

Wherever he had set up home in his life – Cambridge, London, Baghdad, here in Cairo – he always laid out his work space in exactly the same way. His desk sat just inside the door, facing across the room towards the window. There was a row of filing cabinets lined up beside the desk, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves along the side walls and an armchair,

lamp and portable CD player in the corner, with a clock on the wall above them. It was exactly the same arrangement his father – also an eminent Egyptologist – used to have in his study, right down to the pot plants on top of the filing cabinets and the kilim rug on the floor. More than once Flin had wondered what a psychoanalyst would make of the similarity. Probably the same as they’d make of him following his old man into Egyptology: a sublimated need to please, to emulate, to be loved. All the usual crap psychoanalysts came out with. He tried not to dwell on it. His father was long dead, and when all was said and done he was by now so used to that particular furniture configuration it was easier to just let things be. Whatever the emotional subtext.

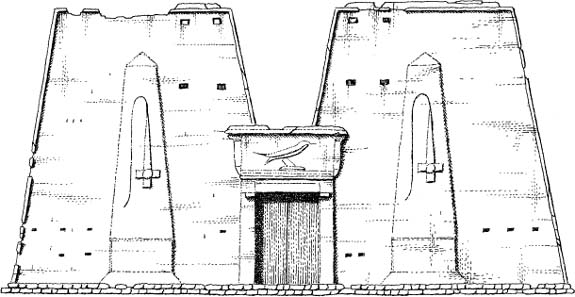

Coming into the room now he paused, as he always did, to look up at the framed print hanging on the wall above the desk. A simple ink line drawing, it depicted a monumental gateway – two trapezium-shaped towers with between

them, about half their height, a pair of rectangular doors surmounted by a lintel. Each tower bore on its face the image of an obelisk with inside it a cross and looping line symbol –

sedjet,

the hieroglyphic ideogram for fire. The lintel also bore an image, this time of a bird with a small beak and long sweeping tail. At the bottom of the print, in flowing script, ran the legend:

The city of Zerzura is white like a pigeon, and on the door of it is carved a bird. Enter, and there you will discover great riches.

He stared at it, repeating the legend to himself – as he always did – and then, with a shake of the head, crossed to the armchair and threw himself down, flicking on the CD player. The melancholy, tinkling strains of a Chopin nocturne rose around him.

It was a ritual he followed every morning, and had done since he was an undergraduate (apparently the spy Kim Philby had sworn by it): a still, meditative thirty minutes at the start of the day – or in this case the middle of it – when he would sit back, block out the world and focus on whatever intellectual problem happened to be preoccupying him at that moment, while his brain was still fresh. Sometimes it might be an abstract problem – how to interpret the mythical struggle between the gods Horus and Set, for example; at other times something more specific: an argument he was developing for an academic paper, perhaps, or the translation of a particularly obscure inscription.

More often than not he would end up pondering some aspect of the Hidden Oasis mystery. This, more than any other subject, was what had occupied his mind these last

ten years. And it was the one to which, in the light of recent events, his mind turned this morning.

It was a complex problem, impossibly complex he sometimes thought: an intricate jigsaw from which most of the pieces seemed to be missing and those pieces that did exist refused to fit into any sort of recognizable pattern. A handful of textual fragments, most of them ambivalent or incomplete; a couple of pieces of rock art, again open to interpretation; the Zerzura stuff; and, of course, the Imti-Khentika papyrus. Not a lot to go on, all things considered; the Egyptological equivalent of trying to crack the Nazis’ Enigma code.

Closing his eyes, the Chopin swirling gently around him, Flin let his mind drift, going back into it all for the ten-thousandth time, meandering through the scattered evidence as though through a field of ancient ruins. He mulled over the various names by which the oasis had been known – the Hidden Oasis, the Oasis of the Birds, the Sacred Valley, the Valley of the Benben, the Oasis at the End of the World, the Oasis of Dreams – hoping that by scrolling through them again he might stumble upon some hitherto overlooked clue. Likewise the

Iret net Khepri

reference, the Eye of Khepri, which he was convinced was more than just one of those figurative phrases so beloved of the ancient Egyptians, but indicated something specific, something literal. If it did he hadn’t yet worked out what it was – and didn’t come any closer to doing so today.

Thirty minutes went by, and then another thirty – the Mouth of Osiris, the Curses of Sobek and Apep: what the hell were they? – until his mind started to cloud and his eyes popped open again. For a moment his gaze wandered

around the room, then came to rest on the drawing above the desk:

The city of Zerzura is white like a pigeon, and on the door of it is carved a bird. Enter, and there you will discover great riches.

Standing, he walked across to it, took it off the wall and carried it back to the armchair, sitting again and balancing it on his knees.

It was the frontispiece – or rather a copy of the frontispiece, the original Arabic script rendered into English – of a chapter from the

Kitab al-Kanuz,

the Book of Hidden Pearls, a medieval treasure-hunter’s guide to the great sites of Egypt, both real and fanciful. This particular chapter was concerned with the legendary lost oasis of Zerzura – aside from a brief and rather cryptic mention in a thirteenth-century manuscript, the earliest known reference to the place.

Although of no intrinsic value, the print was one of Flin’s most treasured possessions, a gift from the great desert explorer Ralph Alger Bagnold, whom he had met shortly before the latter’s death in 1990. Flin had been studying for his doctorate at the time (on Palaeolithic settlement patterns around the Gilf Kebir) and their mutual fascination with the Sahara had meant the two men clicked instantly. A series of happy afternoons had been spent together discussing the desert, the Gilf, and, most fascinating of all, the whole Zerzura problem – magical conversations that had first sparked Flin’s interest in the subject.

He gazed down at the print, smiling, even now – almost two decades later – still feeling the thrill of excitement he had experienced at being in the great man’s presence.

Bagnold had been in no doubt: Zerzura was just a legend, the descriptions of it in the

Kitab al-Kanuz –

heaps of

gold and jewels scattered everywhere, a king and queen asleep in a castle – pure fairy tale, no more to be taken literally than Hansel and Gretel or Jack and the Beanstalk.

There was no question that the

Kitab

was in large part fantasy, crammed full of sensational accounts of hidden riches. Despite that, the more Flin had researched the subject the more convinced he had become that when you stripped away the obvious embellishments, the Zerzura of the

Kitab al-Kanuz

was in fact a real place. Not only that, but – as he had outlined in his lecture the previous evening – it was one and the same as the Hidden Oasis of the ancient Egyptians.

The name itself provided a clue. Zerzura came from the Arabic

zarzar,

or little bird, a clear echo of one of the ancient variations on

wehat seshtat: wehat apedu,

Oasis of the Birds.

The image of the gateway was also intriguing: an almost perfect facsimile of a monumental Old Kingdom temple pylon. The obelisk and

sedjet

symbols likewise signalled an ancient Egyptian connection, as did the bird on the lintel, a clear rendering of the sacred Benu bird.

It was, admittedly, all fairly tenuous, and when Flin had talked it through with Bagnold, the older man had been unconvinced. The similarity in names was almost certainly a coincidence, he had argued – all oases had birds in them – while the ancient architecture and symbols could easily be explained by the

Kitab’s

author having simply copied things he had seen in the temples of the Nile Valley, with which he would most likely have been familiar.

And of course there remained the obvious problem of how – even if Zerzura did exist and was one and the

same as the Hidden Oasis – the

Kitab’s

author had come about his information. The oasis was, after all, supposed to be hidden.

Curiously it had been Bagnold himself who had provided an answer of sorts. There had long been rumours, he told Flin, that certain desert tribes knew of Zerzura’s whereabouts, Bedouin who had stumbled on it by accident and had guarded the secret of its location ever since. For himself he didn’t believe a word of it, but if Flin was looking for explanations that, in Bagnold’s opinion, was the most likely one: the

Kitab’s

author had heard about the oasis second, third or fourth hand from a Bedouin who had actually been there.

‘It’s a fascinating tale,’ he had said. ‘But be careful. More than one person has been driven mad by the search for Zerzura. Keep it as an interest. Don’t let it become an obsession.’

And Flin hadn’t. Not in the beginning. He had continued to explore the subject, to turn up whatever information he could, but it had never been more than a hobby, a diverting sideline to his main area of study. And then he had finished his doctorate and moved out of Egyptology and Zerzura and the Hidden Oasis had been all but forgotten.

Only when his life had gone tits-up and he had returned to Egypt, got involved in Sandfire, had he started looking into it all again, going back over the evidence. Only then had it really sunk its claws into him, his interest ballooning into obsession, and obsession into something bordering on full-blown mania.

It was out there, he knew it, he could feel it. Despite what Bagnold and a hundred others had said. Zerzura, the

wehat seshtat,

whatever you wanted to call it – it was out there in the Gilf Kebir. And he couldn’t find it. He couldn’t bloody find it. However hard he looked.

He stared down at the print, his brow furrowed, his teeth clenched, then glanced up at the clock on the wall.

‘Fuck it!’ he yelled, leaping to his feet. Only fifteen minutes before he was due to start his Advanced Hieroglyphs class. He replaced the print, snatched up his laptop and rushed from the building, in such a hurry that he failed to notice the rotund figure sitting in the window of the juice bar next door, dabbing at his face with a handkerchief and sipping from a can of Coca-Cola.

AKHLA

‘Al Dakla Centeral Hospital’, as the sign on its roof proclaimed, sat on the main thoroughfare through Mut: a modern, two-storey building surrounded by dum palms, and painted green and white like most of the rest of the town. Leaving the Land Cruiser on the forecourt Zahir and Freya went inside where Zahir spoke to a nurse at the reception desk. She motioned the two of them to a row of plastic seats and picked up a phone.

Ten minutes passed, people drifting in and out of the foyer around them, a faint sound of music echoing from somewhere deep within the building. Then a balding, middle-aged man in a white doctor’s coat approached.

‘Miss Hannen?’

Freya and Zahir stood.

‘Dr Mohammed Rashid,’ said the man, shaking her hand. ‘I am sorry to have kept you waiting,’

His English was fluent, a faint American twang to his accent. He spoke briefly in Arabic to Zahir, who nodded and sat down again. With a ‘Please follow me,’ he ushered Freya down a corridor towards the rear of the building, explaining as they went that he had cared for her sister during her final few months.

‘She had what we call Marburg’s Variant,’ he told her, adopting that sympathetic yet detached tone doctors always use when describing terminal sickness. ‘A rare form of multiple sclerosis in which the disease progresses extremely rapidly. She was diagnosed just six months ago and by the end had lost the use of almost everything except her right arm.’

Freya trailed along beside him, only half registering what he was saying. The closer they came to her sister the harder she was finding it to believe any of this was happening.

‘… easier for her in Cairo or back in the States,’ Rashid was saying. ‘But this is where she felt at home and so we did what we could to make her comfortable. Zahir was very good to her.’

They turned right through a set of swing doors and descended a staircase into the hospital basement then followed another corridor, their footsteps echoing on the tiled floor. About halfway down Rashid stopped, removed a set of keys and unlocked a door – thick, heavy, like the door to a cell. Pushing it open, he stood aside to allow Freya through. She hesitated, the temperature around her seeming to drop suddenly. Then, with an effort of will, stepped past him into the room.

It was a large, green-tiled space, unnaturally cold, with strip lights in the ceiling and a vague smell of antiseptic in the air. In front of her, on a trolley, lay a body-shaped form covered in a white sheet. Freya raised a hand to her mouth, her throat tightening.

‘Would you like me to stay?’ the doctor asked.